Empathy

Why It Pays Off to Be Empathic

Animal experiments show that sharing emotions could serve to prepare for danger.

Posted June 7, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Most people believe we feel empathy to help others.

- An experiment published today in Current Biology shows that sharing the fear of others could serve primarily to prepare us for danger.

- With emotional sharing, the people around us become sentinels that reveal where danger looms.

Empathy in its simplest form, sometimes called "emotional contagion," is what makes us feel distressed when we are around distressed people. Intuitively, we see empathy as something generous, other-regarding. We feel empathy for others—it is what moves us to help those less fortunate than us. But is it really an altruistic motive?

Over the past decade, many studies have shown that animals are endowed with emotional contagion, including rats and mice. We even know that when a rat witnesses another in distress, the brain regions it recruits are the same ones we would use when witnessing the distress of our fellow humans, including the cingulate cortex and the amygdala (Paradiso, Gazzola & Keysers, 2021). Such continuity in the brain regions that make us share the distress of others indicates that strong evolutionary forces must be at play over tens of millions of years to stabilize what makes animals share emotions. What are these forces?

Some argue, in line with an altruistic vision of empathy, that it is because mothers must feel strongly about the welfare of the children they must nurse that we share the distress of others (de Waal & Preston, 2017). This motherly motive simply extends to other members of one’s species. A paper published today in the scientific journal Current Biology draws a different—and perhaps more convincing—picture of why so many animals feel distressed when they witness the distress of others (Andraka et al., 2021). The motive is more utilitarian than most of us thought.

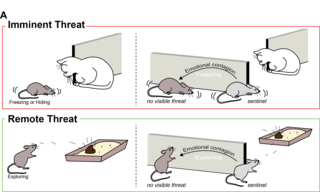

In their experiment, the team let rats witness other rats’ distress. In one case, the distress of the other animal was remote: The so-called demonstrators had previously been exposed to footshocks out of sight of the witness and are now reunited with their cagemate in their safe home environment. In the other, more imminent case, the witnesses watched the demonstrators while they got the footshocks.

When animals themselves are exposed to remote threats, for instance, smelling some fur left behind by a cat, rats rear, sniff, and explore the environment to assess where the danger looms. When rodents are exposed to more imminent threats, for instance, a cat in front of them, they run away and hide if they can or freeze to evade attention if there is nowhere to hide. Surprisingly, the witnesses reunited with the previously shocked rat started to rear and explore, as if they had themselves experienced a remote danger, and those that witnessed the demonstrator receive shocks in front of them started to freeze. They appeared to use the state of the demonstrator to trigger the self-protecting behaviors most appropriate to the nature of the threat that the other animal experienced.

The power of performing these experiments in rats is that we have powerful tools to understand how the activity in the brain regions associated with empathy relates to this phenomenon. The authors used a molecular trick to put light-activated switches on the neurons in the amygdala (one of the regions associated with empathy) that were recruited when rats witnessed the remote or imminent threat demonstrator. They could then reactivate these neurons whenever they wanted by simply shining light on the amygdala.

What the researchers observed was that activating these neurons in a new situation, without a demonstrator present, was enough to trigger an emotional state that mirrored that of the rat they had witnessed days before: Activating the remote threat neurons triggered exploration. Activating the shock observation neurons triggered freezing if the rat had nowhere to hide or hiding if there was a shelter.

In science, the ultimate proof of understanding a system is the ability to produce the desired effect at will. That reactivating these neurons in the amygdala sufficed to trigger an emotional state and behavior of emotional contagion is proof that we are getting close to understanding the nuts and bolts of what makes us share the emotions of others. Most importantly, it shows that the neurons that make us share the emotions of others do not only trigger helping behavior towards others—they also make us protect ourselves.

Hiding when we sense the distress of others and exploring when we witness their worries makes powerful, selfish sense. Dangers often loom out of our sight, and waiting to encounter them firsthand can be lethal. Sharing the emotions of others means tuning into their emotional state as a source of information—a proxy or early detection system that can save our lives.

When we speak of safety in masses, we perhaps think that an aggressor is likely to harm someone else before they harm us. With emotional contagion, being surrounded by others also provides us with an early warning. The people and animals around us become sentinels. The core utility of emotional contagion may thus not have been caring for others but saving our own skin.

This is not to say that sharing the distress of others cannot make us help others. Indeed, even in rats, we showed that the cingulate cortex, another core region of the empathy network, can trigger both emotional contagions and helping in rats. If we inject an anesthetic in that brain region in rats, they not only stop and freeze when they witness another in distress: They also stop to avoid actions that harm others. The same system that helps a rat to trigger protective behaviors when it witnesses the distress of others is thus motivating rats to avoid harm to others.

The same is true in humans. Selfishness and care may thus indeed be deeply intertwined, but for evolution, selfish danger detection may be a more convincing reason to make sure that animals share the emotions of others. Caring is then a welcome side effect of a very pragmatic, and evolutionarily trustworthy, reason to share the emotions of others—saving your own skin.

References

Andraka et al., Distinct circuits in rat central amygdala for defensive behaviors evoked by socially signaled imminent versus remote danger, Current Biology (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.047

Keysers and Gazzola (2021) Emotional contagion: Improving survival by preparing for socially sensed threats. Current Biology (2021) 31(11):R728-R730, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.100.