Religion

The Case Against Viktor Frankl

Rollo May’s attacks on logotherapy.

Posted April 14, 2016 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

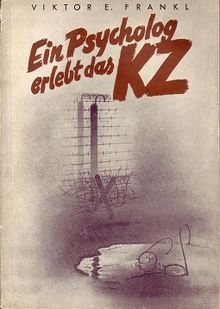

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Viktor Frankl’s landmark Holocaust testimony Man’s Search for Meaning. The book inspired millions with its nevertheless-say-yes-to-life attitude as Frankl, who was interned at Auschwitz in the fall of 1944, urged stoic suffering in the years following the Holocaust. His tragic optimism is also the lynchpin of his own brand of existential meaning therapy called logotherapy, which has been trailed by controversy in the years since.

As I explore in my recent book Viktor Frankl's Search for Meaning (Berghahn Books), there has been some debate whether his brand of therapy was “justified” by his camp experience or “took shape” in the camps. There’s evidence to suggest it may be the former. For just one key example from my book: In 1929, when Frankl was in his mid-twenties and had already finished medical school, he had apparently resolved his personal search for human meaning. As he wrote later, he had experienced the three possibilities from which he thought the meaning of life could be derived: “A deed we do, or a work that we produce, an experience, such as love, and finally the attitude we take toward an unalterable fate.” This sense of resolution was reflected in his description of counseling a patient in 1930. In Frankl’s words:

I was treating her for obsessive compulsive neurosis ... with something like paradoxical intention, and she confessed it worked ... I had compassion and pity for her ... I felt I really had helped her ... I had a feeling like she is mud in my hands ... and I was creating a new person ... this rewarding feeling is the same feeling that comes when I receive letters from all over the world saying how I have helped them.

Frankl claimed that the meaning of his life was to help others find the meaning of theirs, and his conviction is reflected in this recollection. On the other hand, the quote also reveals grandiosity, and it was confirmed by many of his peers that Frankl was a “brilliant prima donna,” as Maurice Friedman put it. Throughout his life, arrogance was combined with “humbled” power to help the psychologically ailing and Frankl maintained a life of simplicity despite his fame.

Published in English in 1957, Man’s Search for Meaning eventually became a worldwide bestseller that was translated into over 20 languages and included in the Library of Congress’s list of the 10 most influential books in America.

Much of Frankl’s support in the U.S. came from religious readers. A feature on Frankl entitled, “A Psychiatrist Discovers God: We Are Born to Believe” was published in the Women’s Home Companion, a publication not known to feature European intellectuals. In the mid-1950s, Frankl began to recruit Methodist ministers and pastoral psychologists to study with him. Among those who went to Vienna were Paul E. Johnson from Boston University School of Theology, Melvin Kimble from Lutheran-Northwestern Seminaries, and Robert Leslie from the Pacific School of Religion. Leslie later published Jesus and Logotherapy, a book which discussed the similarities between logotherapy and New Testament teachings.

But the psychology establishment turned against Frankl in the early 1960s, when Rollo May questioned the therapeutic techniques suggested by Man’s Search for Meaning. In his 1961 book Existential Psychology, May related Frankl’s survival of the concentrations camps but then concluded that "logotherapy hovers close to authoritarianism," because:

… there seem to be clear solutions to all problems, which belies the complexity of actual life. It seems that if the patient cannot find his goal, Frankl supplies him with one. This would seem to take over the patients’ responsibility and ... diminish the patient as a person.

May recognized the pedagogical side of logotherapy and perhaps that Frankl’s therapy was gaining support among pastoral psychologists.

The defense of Frankl was initiated by Rabbi Reuven Bulka in an article published in 1978, "Is Logotherapy Authoritarian?" Bulka’s study of a schizophrenic cured by Frankl was criticized by May for having the "same authoritarian character as fundamentalistic religion." He argued:

... in this therapeutic encounter there are three interchanges between the patient and Frankl. Frankl begins each one of them with a clear and unmistakable ‘Don’t.…. Such categorical instruction illustrates the authoritarian character of logotherapy…..

Frankl first responded by claiming he "wanted to say something to her, not as the Head of the Neuropsychiatric Hospital of Vienna, but rather as a human being to another human being." But after this disclaimer, Frankl re-positioned himself as a medical authority to justify his use of "don’t."

Now, if anyone labels as authoritarian the fact that a medical doctor recommends to his patients to the best of his knowledge and for the sake of their recovery what they should do or should not do, I gladly take the blame. And if anyone labels it "authoritarian" if a medical doctor truthfully tells the patient the prognosis is good, I gladly take the blame. But if the patient says that she "believes" in the good prognosis and anyone compares this "faith" with "fundamentalistic religion," as a member of a medical faculty I must leave such a comparison to the judgment of members of theological faculties.

May’s criticism of logotherapy raises a number of questions. How can a Holocaust survivor and humanist be perceived as an authoritarian? Is there an authoritarian component in an existential form of meaning therapy focused on the patient’s world-view? Is logotherapy prone to diminishing the patient because of religious practice? Or is it more a question of the personality of the therapist and in this case Frankl’s arrogance? In The Impossible Profession, Janet Malcolm depicted the authority of the therapist as the conundrum of psychoanalysis. However one responds to authority in therapy, arguably all forms of psychotherapy have confronted issues surrounding the authority of the therapist; logotherapy is no exception.