Religion

The Indus Valley Civilization: An Ancient Utopia?

In the Bronze Age, Harappans had nothing to kill or die for and no religion.

Updated March 26, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- India’s first civilization was astonishingly advanced.

- But more interesting is what they did not have: no king, army, or religion.

- The Indus Valley Civilization undermines the Enlightenment idea of historical progress as global and linear.

In the mid-1850s, a few years after the British annexation of the Punjab, some railway builders stumbled upon an ancient mound of terracotta bricks at Harappa in the valley of the Ravi. Despite reports of their antiquity, they carted off the bricks for track ballast to support nearly 100 miles of railway between Multan and Lahore.

In 1920, John Marshall, the director of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), ordered a full excavation of the site. Around that time, he heard of another site some 400 miles to the south, which locals called Mohenjo-daro ("The Mound of the Dead") after the human and animal bones that lay strewn among the artifacts. Initial digs at Mohenjo-daro uncovered striking similarities between the two sites, and it became apparent that they belonged to an ancient civilization that pushed back the history of India by several thousand years.

In an article for the 24 September 1924 issue of the Illustrated London News, Marshall wrote:

Not often has it been given to archaeologists, as it was given to Schliemann at Tiryns and Mycenæ, or to Stein in the deserts of Turkestan, to light upon the remains of a long forgotten civilisation. It looks, however, at this moment, as if we were on the threshold of such a discovery in the plains of the Indus.

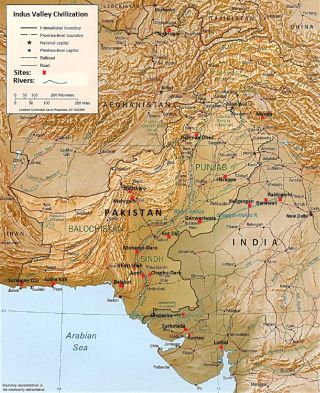

Around 1,000 sites have since been reported, including five major urban centres (Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, and three more). The territory, which straddled the modern India-Pakistan border, stretched some 900 miles along the banks of the Indus and its tributaries, covering an area larger than that of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia combined. The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), or Harappan Civilization, as it came to be called, also had extensive terrestrial and maritime trade connections with, among others, Central Asia, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula.

An advanced early civilization

Early centers were populated from Neolithic settlements such as Mehrgahr in Balochistan. Like the valley of the Nile and the basin of the Tigris-Euphrates, the Indus Valley is a semi-arid floodplain with fertile, irrigated land that did not need much clearing. The advent of settled agriculture in such a place led to a food surplus that supported population growth and urban development.

At their height, Harappa and Mohenjo-daro may each have had 30,000 to 60,000 inhabitants. Although these cities are some 400 miles apart, their construction is remarkably uniform and stable, changing little over the course of a thousand years. The IVC peaked from around 2700 BCE to 1700 BCE and represents the flowering of the Indian Bronze Age.

For context: in Egypt, the first pyramid, the Step Pyramid of Djoser in the Saqqara necropolis, dates from c. 2650 BCE; in Europe, the first Cretan palaces, at Knossos, Mallia, and Phaestos, date from a little after c. 2000 BCE.

Rather than growing organically, Harappan settlements were laid on a similar grid pattern, with large communal buildings and the world’s earliest sanitation system—a degree of urban planning not to be seen again in the subcontinent until the 18th century, when Sawai Raja Jai Singh laid out plans for the "pink city" of Jaipur. Brick houses, some multi-storey, opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes. Each house had access to covered drains along the main roads, suggesting a fairly egalitarian society. The Harappans also had granaries, dockyards, reservoirs, irrigation canals, and public baths.

With a few things missing

But what is more interesting is what they did not have.

First, they did not have palaces or monuments to monarchs. Indeed, this is one reason we know relatively little about the IVC: unlike in Egypt, there are no rich burials like Tutankhamun. The other reason is that the Indus script, like Minoan Linear A, remains undeciphered. After the demise of the IVC, writing would not reappear on the Indian subcontinent for another thousand years.

The Harappans did have citadels but no standing army. The primary purpose of the citadels was to divert or withstand flood waters. Although the standardization of bricks, road widths, and weights and measures over such an extensive area speaks of a strong central government and efficient bureaucracy, the lack of a monarch and standing army argues against the idea of a conquering empire.

Finally, they did not have temples, and so, it is inferred, no organized religion.

Could this utopia have been the first secular, egalitarian state or confederation?

Perhaps the most iconic Harappan artifact is a four-inch bronze statuette, Dancing Girl, depicting a confident teenager caught in a moment with her right hand on her hip and her left hand on the knee. With her chin raised and wearing nothing but bangles and a necklace, she looks much more like a Henri Matisse than anything prehistoric—if only better.

You might be interested in this related article: What Can We Learn From the Indus Seals?

Neel Burton is author of Indian Mythology and Philosophy.