Wisdom

Lessons from the Edge of the African Bush

A Personal Perspective: Wisdom that enhances well-being and human viability.

Posted September 21, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

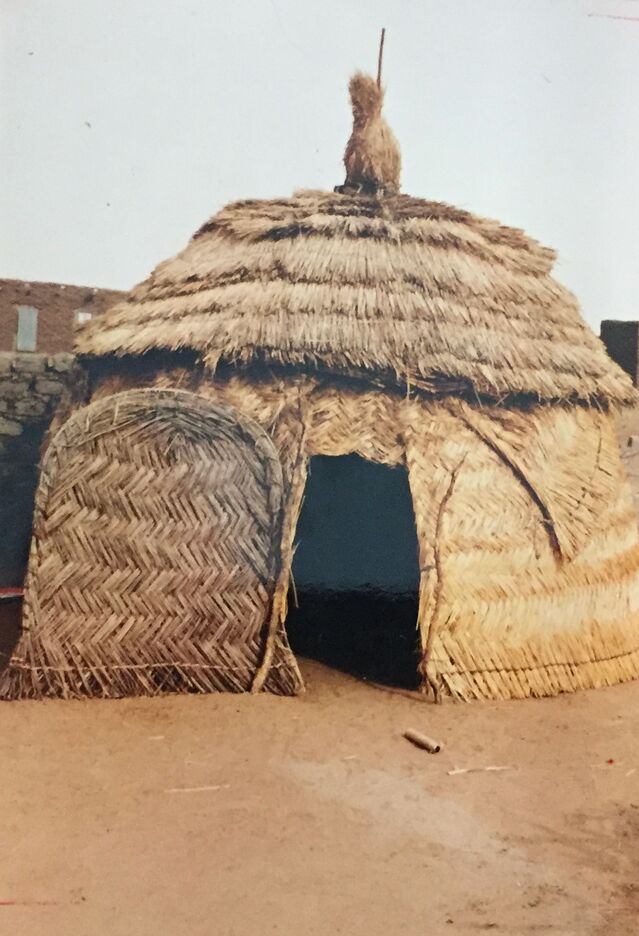

Early one morning during ethnographic fieldwork in the West African village of Tillaberi, Niger, the hottest town in the hottest country in the world, I sat on a beautifully woven palm frond mat in the shade of Adamu Jenitongo’s thatched spirit hut. At sunrise Adamu Jenitongo, my mentor and an important Songhay healer, told me that he wanted to talk to me about “important” matters.

Shortly thereafter, my teacher arrived with a brazier full of hot embers. His grandson brought a porcelain platter on which he had placed a teapot, one large water glass, and two shot glasses.

Adamu Jenitongo poured water into the teapot and measured a shot glass full of strong Chinese green tea and put it on the embers in the brazier. “We’ll drink tea and talk about life.”

Not knowing how to respond, I remained silent.

When the tea water boiled, my teacher added sugar and went through the pouring ritual, emptying the steeping tea into the water glass and returning it to the teapot—three times. He then poured tea into our shot glasses, and we began to sip.

In silence, we looked at one another for a long moment.

“You have been coming here for years.”

I nodded.

“And you’ve learned a great deal.”

“I have much more to learn,” I admitted.

“You do,” he said. “But today I want you to open your ears and understand what’s important.”

“My ears are open.”

“Good,” he said. “Times are bad. People have lost respect for the old words and for the old ways. Our fathers and mothers understood how bad it is for people to speak with two mouths and feel with two hearts. People who speak with two mouths and feel with two hearts anger the spirits of the bush. When the bush is angry there is not enough rain. When the bush is angry there is too much rain. When the bush is angry locusts eat our crops. When the bush is angry sickness kills our people.” He finished his tea.

Several cranes flew overhead. A donkey brayed in the distance. Silence filled the air between us.

Shaking his head, my mentor broke the silence. “Every day our people do things to anger the bush. Every day I make offerings to the bush to set things right, to bring a one-mouth, one-heart balance to the world. That is what the elders taught me. That is my work.”

****

The bush is angry today. When the temperature in Portland, Oregon, soared to more than 112 degrees in June of this year, is it time to rethink our two-mouths, two- hearts priorities? When wildfires and floods bring on mass destruction and the loss of life throughout the world, is it time to critically assess our two-mouths, two-hearts behavioral practices? When Covid-19’s fourth wave brings more disease, death, and economic despair, is it time to reform the environmentally destructive extractive practices that anger the bush? Is it time to acknowledge the wisdom of people like Adamu Jenitongo and admit that human beings have never been the masters of the bush?

Perhaps the power and resilience of Covid-19 is a powerful example, but not the only case, of how our neglect of nature is propelling us toward extinction (see Kolbert 2014; Ialenti 2020; Lynteris 2020; Stoller (forthcoming). The world is sick. Can it be healed?

In the 2021 July-August edition of Anthropology News, five political anthropologists offered a collaborative manifesto for doing anthropology in an admittedly troubled world. They wrote passionately and intelligently about the need for present and future anthropologists to be more collaborative and more politically engaged. They mentioned the need to expand research methodologies and reconfigure disciplinary priorities. In a time of crisis, their manifesto is a multifaceted call to action. One of the contributors David Vine wrote: “The Covid-19 pandemic, the global economic crisis, the unprecedented uprisings for justice have demonstrated the urgency of dedicating our skills, anthropological or otherwise, to healing the world.”

Scholars can produce rigorously researched narrative works that are attuned to an age of crises. Those works, in turn, can convey to the public the profoundly important anthropological, sociological, and psychological insights embodied in the wisdom of indigenous elders like Adamu Jenitongo. During my 17-year apprenticeship with this wise man, he continually stressed how people must respect the bush, how people should be more deliberate and modest, and how human beings should try to live robustly within the limits of their situation. He would tell me again and again that those efforts would enable us to sort through the ever-expanding debris of social life to regain our humanity.

Such are the lessons from the edge of the bush.

References

Stoller, Paul (forthcoming) Lessons from the Edge of the Bush. Writing Anthropology in Troubled Times. (Book manuscript)

Kolbert, Elizabeth 2014 The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York. Picador.

Ialenti, Vincent. 2020. Deep Time Reckoning: How Future Thinking Can Help Earth Now. Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

Lynteris, Chirstos 2020. Human Extinction ad the Pandemic Imaginary. London: Routledge