Resilience

Ties That Bind: The Social Contract in Pandemic Times

How the social contract can enhance resilience during and after the pandemic.

Posted March 29, 2020

As a middle-class American who grew up comfortably in suburban Washington, D.C., I took for granted my good health and never thought about the ongoing presence of basic necessities—food, water, shelter. That changed when I traveled to the Republic of Niger to teach and conduct anthropological research among the Songhay people in Niger, West Africa.

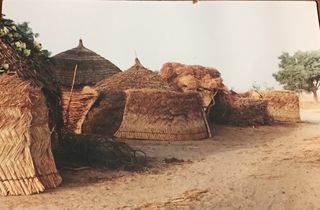

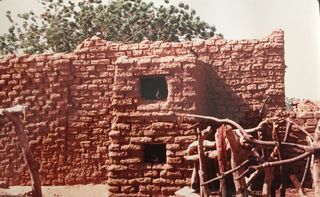

In the rural Nigerien villages where I lived, many people had little to eat. Most villagers had no access to clean water. Houses had no indoor plumbing or electricity. It shocked me to see young children die of infections, malaria, gastrointestinal disease, hepatitis, and tuberculosis. In the region where I lived, roughly one-half of newborns died before two years of age. What a grim reality!

In that grim reality, the Songhay people I met showed themselves to be a strong and resilient people who confronted routine poverty, heat, and disease with admirable dignity. During anthropological fieldwork in Niger in 1984, I lived through a devastating famine. That year, the meager millet harvest the previous October meant that by June, when I arrived, no one had enough food to feed their families. The sight of empty-eyed, emaciated children haunted me.

People told me that to fill their empty bellies, they'd cut bark from trees, pulverize it, and make a paste similar to the millet concoction they'd normally eat. Knowing that people had already died of hunger and its resulting complications, I bought as much rice as I could and put sacks of it on a truck that would take me to Wanzerbe, the famous village of Songhay sorcerers, which had been particularly hard hit. On arrival, I organized the distribution of the rice, which, sadly, didn't go very far in a village of 1,000 people. The evening after my arrival, two toddlers in my compound died. The next evening, an elder in the same compound sickened and suddenly died.

Given the circumstances, my Wanzerbe hosts exhibited a remarkably dignified stoicism. They thanked me for my meager contribution and complained about the government's neglect of rural people. They said that this famine had been more severe than ones in the past.

"This one is bad," an elder told me. "Many people will die, but we'll get through it. We've been through famine many times. We are a strong people. We have always looked after one another. If one compound doesn't have enough food, a neighbor will bring them some millet, or porridge. Together, we carry on."

In the face of death and despair, such resilience made a deep impression on me. It taught me that I should feel grateful to live in a place with plentiful food, electricity, and water. More importantly, my experience with famine and death in Niger taught me the fundamental importance of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's notion of the social contract—the unspoken social bond that binds people together.

In response to the stress and pain of confronting the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, people in America are reinforcing the bonds that tie people together. Neighbors are looking out for one another. Mail carriers risk exposure as they bring letters to our houses. Overworked and over-exposed supermarket workers process our food orders both in-store and at curbside pick-up sites. Delivery truck drivers put themselves at risk to provide food and other goods for those of us who are older or have an underlying medical condition.

Health care workers, some of whom have come out of retirement, risk their lives to care for the sick. Indeed, this public health crisis has provoked us to think and act differently. The pandemic has forced us to reconfigure our routines, which means that many of us take much less for granted.

When our pantries and refrigerators empty out, will we be able to find more food?

What happens if I or someone in my family gets seriously ill? Can we get tested? Will there be an available ICU hospital bed or a ventilator?

In this social environment, many of us might be rethinking our priorities. I, for one, am pondering what is important in my life.

Do people in my family know how much I love them?

Have I reached out to my neighbors?

Do I better understand that human beings are social animals and that human contact—whatever its medium—is the glue that binds us together as families and communities?

Scholars have long known that it is the social contract that sets the foundation for a viable society. In his classic work, The Social Contract (1762), Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote:

"Since men cannot create new forces, but merely combine and control those which already exist, the only way in which they can preserve themselves is by uniting their separate powers in a combination strong enough to overcome any resistance, uniting them so that their powers are directed by a single motive and act in concert."

For me, Rousseau's words ring true. Extraordinary events more often than not provoke a fundamental realization: It is the social contract that enables us to confront the existential issues that define our social lives. Once that existential threat dissipates, it is easy to slip back into the individual routines of everyday life. A return to post-pandemic normality may well prompt a return to an everyday life in which we take for granted the essentials of life-in-the-world.

People like the Songhay of rural Niger and Mali lack many of the comforts that are common in America. Given the economic conditions in which most of them live, the people I know in Niger take little or nothing for granted. Living in a poverty that is hard for most of us to imagine, they are compelled to adhere to the social contact in order to confront the adverse physical, economic, and emotional challenges of their difficult everyday lives.

Confronted with everyday privation, their extraordinary dignity is a model for us all.

In the wake of the pandemic, will we follow it?

References

Rousseau Jean-Jacques 1968 [1762] The Social Contract. New York and London: Penguin Books