Identity

Lessons From West Africa About Identity and the Life-Course

A Personal Perspective: Bull River Sunsets: Reflections on the New Year.

Posted January 2, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Early in 2022, I experienced a magnificent Bull River sunset near Savannah, Georgia. The Bull River flows through an intricate maze of breathtaking wetlands that snake their way toward the Georgia coast. If you are lucky enough to know someone with a boat, you can follow the current toward the land’s end. You can see a dolphin or two, breathe in the salty scent of the ocean, and feel the coastal breeze. If your timing is good and the weather is clear, you might be able to see a beautiful sunset over the low country to the west. Reflecting on that river sunset always compels me to think about where I’ve been, where I am, and what the future holds.

When I think about my past, I am grateful for the moral compass my parents provided. I am also thankful for the scholarly training I received, first in linguistics and then in social anthropology. I grew up in a working-class Jewish household. No one in my family expected me to become a professor and scholar. People in my family had little understanding of the social sciences and why they might be important. What's more, they could not imagine why I would want to move far away to live and work in the remote regions of West Africa.

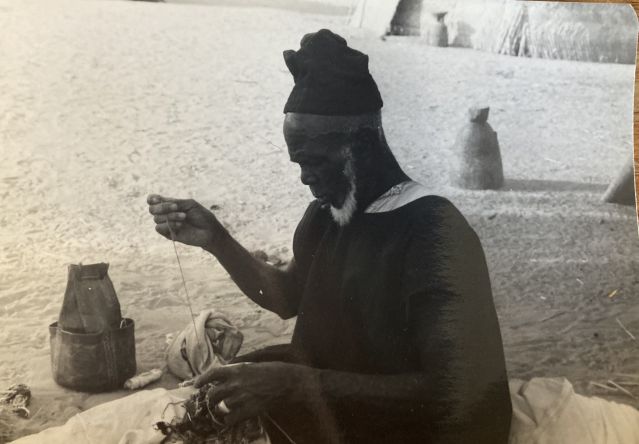

I am not the first person to hear a chorus of familial doubt. Even so, I stood my ground and followed my passion. Indeed, I learned a great deal from mentors who took me under their care and patiently taught me their ways. They introduced me to a world of spirit mediums, herbalists, and healers. My teachers among the Songhay people of the Republic of Niger knew little about my background or early life in the United States. They tended to categorize all outsiders as "anasaara." An anasaara was usually an expatriate teacher, a European businessperson, a French official, a missionary, or an American Peace Corps Volunteer. At first, the elders in Mehanna, the town where I first worked, wondered why an anasaara would choose to live in the emotionally and physically demanding conditions of a remote rural town in Niger. Over time, the elders thought less about my “subject position” and more about my desire to respect their practices, their ancestors, and their spirits.

“Without respect,” Adamu Jenitongo, my principal Songhay mentor liked to remind me, “there is nothing.”

For more than 17 years, Adamu Jenitongo taught me about the mysteries of divination, spirit possession, herbal medicines, and sorcerous potions. He taught me about a way of life that has shaped who I became and how I understand the world. He discussed with me the relation of the village to the "bush." He never tired of talking about the necessity for people to respect one another —no matter who they were. Above all, he stressed the need for people to respect the power of the "bush"—of nature—to ensure the future of the village and the world. “If people do not respect the power of the bush,” he liked to say, “the bush will consume the village. We are not masters of the bush. We need to demonstrate our respect for it."

During our time together we would sit, gaze at the Niger River, and talk about life in the world. In the late afternoon, I would often take a dugout canoe, find a peaceful spot among the river reeds and rice paddies, and reflect on his lessons. His words have sustained me in these times of political, epidemiological, and environmental turbulence. They still resonate profoundly.

When I think about where I am today, I wonder why Adamu Jenitongo entrusted me with so much Songhay knowledge—incantations, healing recipes, ritual formulae, and social philosophy. I do know that he wanted me to share with others what I learned from him. He wanted his words and his knowledge to be passed on, which is what I have tried to do through my teaching, articles, and books. At the 2022 Annual Meetings of the American Anthropological Association, David Signer, a Swiss journalist who was covering the academic convention for his newspaper, sought my opinion about the recent push to decolonize the social sciences. He wondered if my "privileged" subject position as an “anasaara” made it uncomfortable for me to write about West African esoteric practices. I have since reflected on his important questions, which compelled me to remember what Adamu Jenitongo thought about the nature of identity and the obligation to safeguard and share knowledge.

“What matters is less about your origins, my mentor told me, “and more about what you become. You are not of my blood,” he said to me, “but I can see who you are and feel I can trust you with the burden of knowledge.”

A part of that burden is making certain that the knowledge you attempt to convey is "correct." If you are made aware of an error of interpretation, which is unavoidable in life and in scholarship, it is your obligation to set the record straight. Careful consideration about what you say and write demonstrates respect for the past, the present, and the future. Such care ensures that precious knowledge is passed on to the next generation. I will always be grateful to the mentors who took the time to pass on their knowledge to me. As I anticipate another boat ride on a beautiful river in 2023, I think about what I can still pass on, what is important in today's world, and how I can continue to contribute to my family, friends, students, and discipline.

The arrival of a new year marks a time for us all to appreciate where we are and where we are going. Each of us, in our own way, is a custodian of knowledge. For me that means that I will continue to share the knowledge that my West African mentors conveyed to me, hoping that it helps to empower the next generation to follow their own path with enhanced respect for nature and for one another.