Relationships

Which Works Better, Psychotherapy or Psychic Therapy?

As Greek mythology shows, magic can't bring a lover back.

Posted July 23, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Although it sounds old-fashioned, belief in love magic is as popular as ever.

- If magic really worked, mediums would be living perfect lives. Are they?

- Psychotherapy, not psychic "therapy", is the only way to cope with a broken heart

This post is the second in a series based on my new book, How to Get Over a Breakup: An Ancient Guide to Moving On. For part 1 see here.

In a previous post I introduced a delightful but forgotten poem from ancient Rome titled Remedies for Love. In it, Ovid (pronounced Áh-vid), the poet, poses as a relationship counselor no different from his counterparts today. And although he's clearly joking in many cases — more on that in my next post — he's clearly not joking in many others. Like a modern-day psychotherapist or doctor, he cites case histories and dispenses lightly medicalized advice to help cure us of unrequited love. He genuinely seems to want to help us cope with unrequited love and grow past it.

As I described in my first post, the first six of Ovid's 38 recommendations are eminently practical. They focus on positive, active steps you can take to stop dwelling on your ex and move on: take a long trip out of town, find a new hobby, focus on school or your career, and so forth. Probably everyone would endorse this.

And yet after these initial commonsense, practical recommendations, recommendation #7 is totally different and a complete surprise. It seems to come out of nowhere. He suddenly warns us:

#7: Place not your faith in spells, abracadabras, and charms.

Huh?

If you’re a secular-minded reader today, you might simply smile at this suggestion and move right on. Spells? Charms? “Love magic”? Come on.

You might also assume this question was settled a long time ago. Three and a half centuries ago, nineteen women and men were hanged in Salem, Massachusetts, some for "bewitching" others. Two centuries earlier in Europe, many thousands of women and men were burned at the stake for the crime of "harmful magic." Today we look back on those episodes in shock and shame.

And yet the belief that you can make someone fall in love with you, or back in love with you, just won’t go away. Even today, "spiritual healing" is big business, and not only in far-flung parts of the globe. University towns are crawling with purveyors of psychic readings, crystals, energy transfers, tarot cards, and astrology. As I write, for instance, the hamlet of Lily Dale in western New York state is hosting its annual summer conference for mediums. Even among educated people, there is clearly a robust market for these services.

But do they work? In a recent article in Teen Vogue, a New York-based astrologer and tarot card reader named Lisa Stardust hedges the answer. They write:

Love magic is an extremely controversial topic in spell work. There are many perspectives about the ethics of bending another’s will for their admiration. Luckily, there are rules that apply when casting such spells. So if you want to fall in love but don't want things to get dark, you're in the right place.

Stardust is certainly correct to say the ethics of love spells are alarming and abhorrent, because if they did work, they’d be indistinguishable from kidnapping, enslavement, and rape.

Luckily—no pun intended—love magic doesn’t work. Stardust themself makes the point repeatedly:

Love magic is the act of attracting, well, love! Don't be fooled, though: It won't make someone fall in love with you. … Be aware that spells aimed to trap another person or manipulate their will won’t work.

Nevertheless, Stardust goes on to claim that scented baths, astrological candles, slipping a note in a jar of honey, and sleeping with a sachet of spices under your pillow will help you with falling in love.

This is all bunkum, of course, and it brings us back to Ovid and his recommendation, because the situation was no different 2,000 years ago in his day.

Greek and Roman literature features quite a few pieces that imagine the scenario of a lovelorn, average woman enlisting the help of a witch to bring her man back to her. The poets Theocritus and Virgil each wrote a poem on the theme from the forsaken woman’s perspective, and Horace wrote one – Epode 5 – from the witch’s perspective. And Sophocles’ play Women of Trachis dramatizes the disastrous efforts of Deianeira, Hercules' wife, to win her husband back. All these stories suggest love magic works, even if not always as intended.

Yet here is where Ovid, our poet, goes one better. He identifies two examples in Greek mythology in which the witch herself is in love with a man who does not requite her love—and who yet fails to win him back. Boom! That is the trump card that shows that love magic doesn't work.

Ovid focuses on two “case histories,” and if you know any Greek mythology then you’ll know and love them both.

First is Medea. Ovid stops his poem to address her directly:

Please. What good did exotic botanicals do you, Medea, when you were hoping to stay home in your father’s abode?

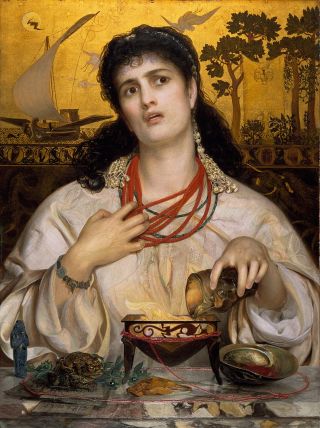

Medea is the first famous “witch” in Greek mythology. As a young woman she helped the hero Jason complete a quest and make his getaway from her father's home--only to then find herself abandoned by him when another woman, Creusa, caught his eye. (Euripides’ play Medea dramatizes these events vividly.)

In the second “case history,” Ovid reimagines a famous episode of Homer’s Odyssey. In it the enchantress Circe welcomes the hero, Odysseus (called Ulysses in Latin), and his crew into her home. She turns them all but Ulysses into swine, and though Ulysses is eager to get home to his beloved wife Penelope, she detains him there for a year. Finally he summons the strength to leave her.

Given this fact pattern, Ovid cuts right to the heart of the paradox. He puts a tough question to the lovelorn enchantress, once again addressing her directly:

Circe, what help, per se, were your birthright wort-plant concoctions, if just a nice little breeze whisked your Ulysses away? Try as you might, you couldn’t dissuade your “houseguest” from leaving. Hell-bent on fleeing, he snuck out and away—with full sail. Try as you might, you couldn’t help getting engulfed in the blazing fire; no, Love set in, living rent-free in your head. No, you could change human beings into thousands of shapes, but you couldn’t change or transform laws holding sway in the heart.

Do you see the point? In both cases Ovid is saying, as would Jesus a couple decades later, “Physician, heal thyself!” If lovelorn witches cannot heal their own broken hearts, then what good (asks Ovid) could psychic “therapy” possibly be?

For all his light touch , there’s a profound and practical insight here, though Ovid doesn’t spell it out. It’s this: Next time you meet a medium, ask yourself: How are all her magic charms working out for her? Does her life look prosperous, wealthy, happy, perfect? If not, why?

If anything can help heal a broken heart, says Ovid, it’s psychotherapy, not psychic therapy. Or as he puts it,

Magic—because that’s what it is—is obsolete. The mystical guide of my song, Apollo, is teaching us harmless relief.

References

Fontaine, Michael (translator). 2024. Ovid: How to Get Over a Breakup.: An Ancient Guide for Moving On. Princeton University Press.