Gender

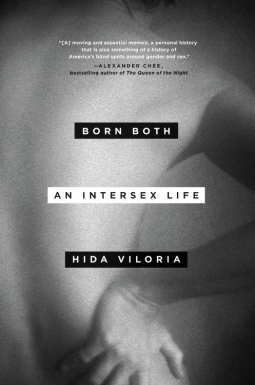

Born Both: Intersex and Happy

Ariel Gore talks to intersex feminist Hida Viloria about her new activist memoir

Posted May 24, 2017

When I call something an “activist memoir,” I don’t mean that it’s a memoir chronicling someone’s activism—although it may be that, too. What I mean is that the creation and existence of the book itself is activism. When a once-silenced outsider voice pushes itself into this form—the book—that patriarchal publishing has kept so densely colonized, we should pay attention.

Hida Viloria has written an activist memoir.

If you read Born Both (Hachette Books, 2017), it will impact you.

Born intersex in the late 1960s to a Colombian physician father and a Venezuelan ex-school teacher mother, Hida was registered and brought up as female without being subjected to medically unnecessary “normalizing” genital surgeries—or intersex genital mutilation.

I talked to Hida from he/r home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, just as s/he returned from the book tour promoting the new memoir.

Ariel Gore: I imagine you could write a whole new book around your experience putting Born Both into the world. Has any part of it been surprising?

Hida Viloria: Even though I worked very hard for a long time on this book, part of me wondered if the world was really ready to react positively to a topic that is still quite obscure and stigmatized. Yet deep down I felt that the central themes of struggling to find oneself, love oneself and embrace parts of oneself that are deemed different are so universal that they might resonate and speak to many readers. So I’m thrilled that people are getting the message, and in some ways I don’t find it too surprising because I think people are more introspective, self aware, and social justice minded than ever.

Ariel Gore: I like the way you talk about your relationships with your parents in the book. You describe your father as very challenging at best, but you also credit him with leaving your body alone at birth. Can you talk about what turned out to be an unusual choice on your parents' part?

Hida Viloria: I think ultimately it was really just common sense, because everyone knows that surgery is risky, so why would you risk your baby’s life for a cosmetic procedure? My father was a physician so he couldn’t be lied to about the procedures. I know another intersex activist whose father is also a physician and chose not to subject him to genital surgeries either. Unfortunately, most parents aren’t doctors so they ignore this common sense and go with their doctors’ recommendations.

But isn’t it interesting that some doctors are recommending procedures that other doctors won’t subject their own children to?

And while two cases may not seem like a lot, I think they’re significant when you consider that it’s not that common to be a doctor, much less one with an intersex kid. I think it just shows that doctors are more careful about protecting the ones they love versus patients who are basically strangers.

Ariel Gore: When I was pregnant with my last kid, my then-partner always said she hoped the baby would be born intersex. After reading your book I get what she meant: That we could be good parents for an intersex kid. Is there more information you wish all new parents had access to?

Hida Viloria: There’s a lot of information available online about the harms of subjecting intersex children to nonconsensual sex reassignment surgeries and hormones, but many parents don’t seem to buy it because they’ve said, even publicly, that despite hearing about this they still thought it’d be worse to leave their kids with their non-binary bodies intact. To me, this indicates that what parents really need is to be exposed to people who haven’t been subjected to these practices. To meet them or hear their stories through whatever means possible.

I thought that writing my memoir would be the best way to show parents that it’s possible to grow up as an intersex person—without any unnecessary medical treatment—and be a happy, thriving adult who is loved and loves themselves.

I want parents to know that intersex kids can decide who they are for themselves and have that turn out beautifully.

Ariel Gore: At this point in your life, how do you define gender?

Hida Viloria: I think gender is both an expression and a feeling. I define gender as something that comes from within us and is expressed to the world like a unique, non-audible song that all humans sing. We can try to imitate the most accepted, popular songs but we can never exactly duplicate them so in the end, as I’ve written about, each song, like our fingerprints, is an original: our genderprint.

Ariel Gore: You talk in Born Both about the ways that a lot of trans folks were very accepting when you were first discovering your intersex status and coming out, but that being intersex and being trans are very different. Can you get into that a little more? For people just learning about what it means to be intersex or non-binary, I think you have some really simple ways to frame things.

Hida Viloria: I did connect with a lot of supportive trans people who were challenging traditional gender stereotypes and it was wonderful. There were also trans folks that I didn’t feel supported by because they disliked that I expressed myself in both feminine and masculine ways. I’ll never forget this one time when I went out looking like a girl in a dress and makeup, and some transmen I was friends with who were used to me looking like a boy completely ignored me. I stopped one of them who’d always given me a warm pat on the back when he saw me and said, “Hey it’s me Hida, I think you didn’t recognize me,” and he just looked at me and said, “No, I did,” and kept walking.

I realized that night that some trans people had their own strict rules and criteria about gender presentation, and that I’d only been welcomed because I appeared to fit into them. The minute I broke the rules by expressing my femininity as well as my masculinity, I was rejected, and it was both painful and infuriating that they weren’t more accepting. The terms non-binary (which means someone who feels themselves to be neither a man or a woman, or is both) and gender-fluid (which means someone whose gender identity and expression shifts over time) didn’t exist yet, but that’s what I am and what I was expressing and some folks had negative opinions about it—even some intersex folks.

Which brings me to an important point about being non-binary: Like being a man or a woman, it’s not determined by your sex characteristics. This means that not all non-binary people are intersex, and not all intersex people are non-binary.

In fact, intersex people are often more pressured than non-intersex people into being masculine men or feminine women—by doctors trying to force us into those identities, or our parents, or both—so it should come as no surprise that many of us identify as men or women.

Things are much better today, but people’s attachment to fitting into the man/woman gender binary still negatively impacts non-binary and intersex people. For example, in 2014, I read an article about hormone blockers which featured a trans man explaining that no matter how masculine he had felt and dressed before he transitioned, it was always contradicted by his body’s femaleness. He said that it had made him feel like an “in between freak,” and others relayed similar feelings. I was thinking, Wow, some of us are born or feel in between, thanks a lot. Then, when asked about intersex people, the medical expert interviewed in the article, Dr. Norman Spack, referred to us as “accidents of nature.” All I could think was how painful it must be for parents of intersex or non-binary kids who are allowing their children to be who they are to read this.

It was a glaring example of the trans and intersex/non-binary communities’ differences, but it’s a shame for them to be expressed in these harmful ways because it’s completely unnecessary.

There’s room for all of us to be who we are and have our experiences without disrespecting others in the process.

For example, people who are binary can express that without referring to non-binary people as “freaks.” They can simply say, “I hated looking in between,” which honors their experience without putting down non-binary and intersex people’s.

Ariel Gore: What’s most important for psychologists and mental health providers to get about intersex and non-binary clients?

Hida Viloria: I think the most important thing for psychologists and mental health providers to get about intersex and non-binary clients is that there’s a big difference between having mental health issues because of what you are (schizophrenic, for example), and having those issues because of rampant prejudice against what you are. For example, I’ve seen papers where intersex people are portrayed as being innately prone to mental health issues, and this used to justify “corrective” medical treatments, instead of acknowledging that many of us suffer from these issues precisely because we’re victims of these medical treatments and other forms of interphobia (negative attitudes against intersex people). To me it’s similar to the way psychology used to recommend “curative” medical treatments like electric shock therapy for gays and lesbians who were having a hard time living in their homophobic surroundings.

I think mental health care providers need to be aware that intersex people, and non-binary people to a lesser degree, are in a similar position today to where gays and lesbians were fifty years ago, when being homosexual was so stigmatized it was classified as a psychological disorder.

Being intersex is currently classified as a medical disorder due to social prejudice and I’ve sometimes heard psychologists refer to us this way—which is harmful to our self-esteem. So I think mental health providers need to check themselves to make sure they don’t mirror the current prejudice against intersex and non-binary people, because if they do they’ll be transferring this onto us with negative impact.

Also, I think mental health care providers need to recognize that internalized interphobia is extremely common in the intersex community, especially among the majority who were harmed by medical procedures in their youth. In fact, internalized interphobia in this group is so prevalent that I’ve sometimes had health care providers discount my experience or act like I’m strange because I don’t have negative feelings about myself and actually like being intersex! For example, I once had my life experience radically misinterpreted in a medical journal by two experts on intersex issues who lumped me into a group of intersex individuals who’d been too ashamed about their bodies to have sexual relationships. One of the experts admitted to me later that so many of the intersex people she’d worked with had felt bad about themselves that she’d glazed over the fact that I didn’t.

It’s important that mental health care providers realize that those of us who were subjected to non-consensual sex reassignment have a host of mental health issues which those of us who weren’t don’t.

It’s also critical that they acknowledge that intersex people can feel good about our sexuality, our bodies, and about being intersex in general, especially when given the right to decide for ourselves who we are. Otherwise recommendations for harmful “curative” medical procedures will continue.

Ariel Gore: You talk about the misconception that intersex people can’t be loved—and maybe can’t happy. Do you think that’s what a lot of the fear boils down to? Born Both radically blows up that notion.

Hida Viloria: I think that a fear that intersex children and future adults will be unlovable is the top motivator for why parents subject their babies to medically unnecessary sex reassignment surgeries. In some cases, it’s the parents themselves who find their intersex child unlovable, and want to make them more typically male or female. Every parent, after all, hopes that their child will be happy and loved, and has their own culturally imposed ideas about what makes someone lovable.

In our society everyone is supposed to be either male or female, and so it’s natural that parents would worry that someone who is something else will not be accepted. However, what I’ve seen firsthand is that people love people based on who they are, and are willing to accept many differences, including people with bodies that are different from our male and female norms.

In fact, even the gynecologist I saw recently was shocked to learn about my activism and that babies are harmed in these ways, because she’d noticed that my body was different but thought it was perfectly okay.

Ariel Gore: What are some next steps in ending intersex invisibility and oppression?

Hida Viloria: I think the next step to end intersex invisibility is for intersex people to come out by the thousands in all segments of society. We’ve seen that people include communities more when they actually know people from those communities. So we can educate all we want about the fact that intersex people exist—and I do and think it’s extremely important—but if people don’t know that they know an intersex person because most of us are living secretly, we still remain relatively invisible.

Having intersex people come out en masse would also go a long way in ending intersex oppression, because it’s a lot easier to turn a blind eye to oppression when you think it’s not affecting anyone you know. That said, not everyone is brave enough to come out as members of a community that’s discriminated against, especially if there’s no legal protection from that discrimination. That’s why the non-profit I founded, The Intersex Campaign for Equality, has been working with Lambda Legal on federal gender recognition for intersex and non-binary adults who want it. Our associate director, Dana Zzyym, is suing the State Department for a passport which accurately lists their sex as neither male nor female. It's groundbreaking and it also helps non-binary people who want their gender identity acknowledged, since sex is conflated with gender in the law.

We know that in order to be protected from oppression you have to be acknowledged as citizens under the law. There’s currently a bill in California to allow citizens to have their sex recognized as non-binary on their driver’s licenses, but a doctor has opposed it, saying, "I disagree that this society is ready for a third sex."

Ready for us? We've always been here! That's like saying, back when it was discovered that the Earth isn't flat, that society wasn't ready for a round planet—people did say that, but the sanity in acknowledging scientific reality eventually won out.

Doctors know we’re here because there’s a big fuss when we’re discovered as babies, but then they give us sex reassignment surgeries and say we’re really males or females who just needed certain medical treatments. They’re trying to make us disappear but it won’t work because more and more doctors and parents are realizing that everyone has the right to decide who they are, and more and more of us are coming out and demanding to be recognized as intersex.

In the end, love and acceptance always win.