Magical Thinking

Clay Routledge: The Religious Mind is in the Heart

Clay Routledge on his upcoming book on motivation and supernatural belief.

Posted July 2, 2018

Dr. Clay Routledge has spent much of his academic life researching basic human existential motivations and the impact of those motivations on beliefs about the supernatural, physical health, well-being, and intergroup relations. And he’s good at it. He’s published over 90 scholarly papers and research reports; he’s co-edited books on existential motivation (in press), on meaning in life, and is currently co-editing an upcoming book on religion, spirituality, and existentialism; he’s authored a book on nostalgia; and he’s written a new book on the existential motivation toward meaning and supernatural belief.

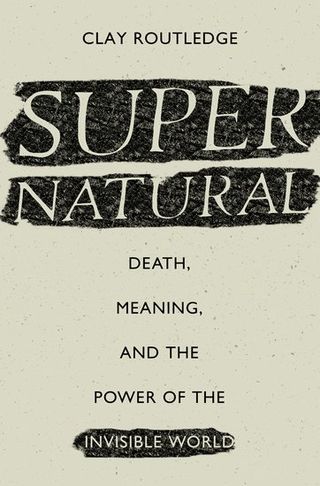

His upcoming book is titled Supernatural: Death, Meaning, and the Power of the Invisible World (available from Oxford Univ Press and Amazon).

I occasionally have the pleasure to work with Clay, and have had the opportunity to read his upcoming book, Supernatural, before its release. In many ways it offers an easily-understood and accessible perspective on the science on existential motivation and supernatural beliefs. So I spent some time with Clay for an email-based interview to learn more about him and his work, the book and the science, and the broader context. What follows is a transcript of that interview.

KV: Before we get into your book and related topics, can you tell us a bit about yourself—your academic background and expertise, your research activities, and how you became involved in that work?

CR: I was trained as an experimental social psychologist but now think of myself more broadly as a behavioral scientist because the questions I am interested in involve different subfields of psychology as well as disciplines outside of psychology, though the human mind – how we as individual brains think about and interact with the world – remains at the center of my work. Much of my research has focused on psychological motives, particularly existential motives.

As the son of Christian foreign missionaries, I suppose I have long been interested in religion and other cultural worldviews that help people navigate questions about death and meaning but it wasn’t until I started graduate school in that I was exposed to the scientific study of existential motives. The 9/11 terrorist attacks happened at the start of my first semester of graduate school and this really impacted me. The idea the people would not just kill others for their ideology but purposely annihilate themselves really struck me as an important question for psychology considering that humans, like other organisms, generally try to stay alive. These weren’t impulsive acts or the result of mental illness. They were carefully planned and coordinated attacks carried out by people of sound enough minds that a terrorist organization felt they could be relied upon to train for and complete a complex mission. I happened to be at the University of Missouri where one of the leading experimental existential psychologists was working and got myself plugged into his lab to do studies on how existential motives inspire risky behavior in the service of a meaning-providing ideology.

KV: You have a new book coming out in June. Can you tell us about that; who is your audience and how will it contribute to their understanding of existential motivation, meaning, and supernatural beliefs?

CR: The book is being published by Oxford so people may think it is for academics and those who like academic-style writing but I actually didn’t write it for those folks. I wrote it for non-academics who are interested in questions about the psychology of meaning, religion, and supernatural beliefs. In other words, I think it is totally accessible to most adult readers, though academics, especially those who don’t study existential issues, will also find it of interest, I hope.

I think it will contribute to people’s understanding of these issues because though many folks won’t be surprised to learn there is a connection between our search for meaning and our interest in the supernatural and related ideas, I suspect most don’t know about the diverse and fascinating research that has been done on this topic. I also think there are many findings that people will be very surprised about. Critically, I challenge some very common beliefs about both theists and atheists and make the case that they have more in common than many realize.

My ultimate goal with this book is to offer a new way of thinking about supernatural beliefs, curiosities, and questions. And the book is just one piece of my broader proposal that we need to rethink our views on the nature or religion. A lot of people have a blank slate view of religion, that it is something completely social or cultural, that is, something we are taught and then internalize. I come at it from the other direction, that religion or at least the characteristics and ideas that become religion come from within us. They are part of what it means to be human.

KV: In Supernatural you write that, “Meaning is found in the heart, not the brain,” and you largely focus on how existential concerns may lead to some of the same basic motivational processes—at least on an implicit and psychophysiological level—for believers and non-believers. That sounds fascinating; can you tell us more about that?

CR: Much of the psychology of religion has taken the approach of asking people about specific traditional religious beliefs and practices. This approach is very useful for understanding religious self-identifications and related correlates, but the foundational aspects of religion such as the dualist belief that humans have both material bodies and nonmaterial and transcendent essences are often not fully captured in religious questionnaires. Also, there is a difference between a firm religious belief and a curiosity or openness to spiritual and related ideas. Add to this the possibility that many of our more intuitive inclinations are not being picked up in questionnaires that give us a chance to respond with a more thoughtfully manicured presentation of how we like to think of ourselves.

Why does all this matter? It matters because our work and the research of others suggests that we often rely on more intuitive processes when navigating existential questions related to meaning in life. An example everyone can understand is love. Most people would agree that close relationships give us meaning and the research certainly indicates this is the case. And most would probably also agree that love is an intuitive feeling, not a rational calculation. So we intuitively feel love and that makes us feel meaningful.

The leap of faith or hope people take regarding supernatural ideas similarly appears to involve intuition. Religion certainly has more analytical components just like relationships do. The most seriously committed people of faith live very thoughtful and self-disciplined lives that require a considerable amount of rational thinking. Also, the religious and secular life goals that contribute to meaning similarly involve careful planning and action. However, I would argue that intuition is important for the supernatural nature of religion and the meaning we derive from it, again, just like intuition is important for the meaning we gain from love. In other words, a life of meaning requires a certain level of intuition. Religion or any meaning-providing belief system is probably at its best when it properly balances intuition and more analytical, goal-focused thinking.

KV: And what about explicit/conscious supernatural beliefs? There exist many varieties of religious beliefs, as well as atheists, agnostics, and other skeptics. If everyone experiences the same basic existential motivation toward supernatural beliefs, then how can we understand the continued existence of normal healthy-functioning atheists and other skeptics—why hasn’t this motivation led to universal religious belief?

CR: I think we need a lot more research on atheists and am glad that we are starting to see more. Even if you look at the pretty basic questions asked by organizations like Pew you can see that there is diversity in the spiritual inclinations of atheists. There are neurological and cognitive-based reasons to argue that a very small percent of people are true atheists. But there are also reasons to believe that many atheists are really more superficial or social atheists – people who view themselves as nonbelievers but who actually engage in supernatural thinking. Some atheists are angry at religion or even God and so view atheism as a protest against belief. Some, particularly young people, may see religious belief as not cool, something for old people. And many have benefited from a socially and economically privileged life that has not stress-tested their atheism.

Consider, for example, a recent study in New Zealand that observed an increase in religious belief among nonbelievers who were personally impacted by a major earthquake or research showing that atheism is associated with poorer psychological wellbeing among people in economically disadvantaged areas but not in more affluent ones. Think about the following example. It is easier for a rich person who lives in a very safe neighborhood to become philosophical about the value of the police. This person can say with little consequence that the police are bad and we don’t need police, that all the police do is create problems. But you can bet with near certainty that this individual would be quick to call the police in an emergency. In other words, the safer, more comfortable, and prosperous a society is, the less outwardly religious it may appear to be.

I say “outwardly” because even when people live where they feel physically safe and can easily meet basic needs, existential questions about meaning remain. Many atheists may be one serious existential threat away from finding religion or looking for a substitute for it. From this perspective, true atheists are the few who may simply lack the underlying cognitive characteristics that allow for supernatural and related spiritual thinking. They may also be the rare individuals who are low in the need for meaning. So I don’t think the trends of declining religion are evidence for a decline in people’s religious nature. We wouldn’t say that because people are spending less time in face to face social interactions that the social nature of humans has diminished. I don’t think the religious nature of humans has diminished either.

KV: In recent years, nearly every poll in the West suggests an overall decline in religious faith and an increase in the so-called religious “nones.” However, in Supernatural you propose that people might perhaps exchange one variety of supernatural beliefs for another. Can you expand further on that idea for us here?

CR: In the book, I discuss a number of trends related to supernatural and paranormal beliefs that are in the opposite direction of declining religiosity. Many surveys in the US and other Western nations reveal that people aren’t abandoning all supernatural and related beliefs. As these countries become less invested in traditional Christian beliefs, they become more interested in nontraditional spiritual practices, ghosts, UFOs, healing crystals, psychic powers, and so on.

For example, my colleagues and I recently replicated research documenting an inverse correlation between religiosity and belief that intelligent alien life exists and is monitoring humans as well as conspiracy theories about government cover-ups regarding UFOs. After replicating this effect, we sought to further explore why it is that the less religious people are the ones more into aliens and UFOs. We predicted that part of it is about the need for meaning in life. Religiosity is generally positively associated with meaning. If nonreligious people see life as less meaningful but remain motivated to find meaning, they may be more inclined than those who already have a meaning-providing religious worldview to be attracted to ideas that would suggest humans are not alone in the universe. We found support for this idea using statistical modelling that linked low religiosity to low meaning to a greater desire to find meaning to beliefs about aliens and UFOs.

To be clear, aliens and UFO monitoring aren’t necessarily supernatural but they are outside of an evidence-based understanding of our world. To believe in them requires a leap of faith. And many UFO-related beliefs have a very religious flavor. They involve feeling like powerful beings are watching over us and may one day welcome us into a cosmic community. Of course, many nonreligious people do hold these beliefs, but there are many unorthodox supernatural or paranormal ideas and beliefs that nonreligious people are attracted to in their search for meaning and cosmic significance. And there are secular ideologies such as transhumanism that have what I call supernatural-lite qualities. They aren’t explicitly supernatural but appear to be driven by the same cognitive and motivational processes and often end up looking very similar to religion.

KV: In Supernatural, you suggest that faith in religious supernatural beliefs may offer some benefits for physical health, mental health, and societal living. Can you tell us about what some of those benefits are, and whether you find that there are any downsides to supernatural beliefs?

CR: Religious supernatural beliefs promote meaning, and meaning is a predictor of wellbeing and mental health. These beliefs have also been shown to help people cope with stress and the life events that challenge meaning. This might be because meaning motivates people.

That is, people who feel they have a purpose are more driven to take care of themselves, to work hard, to live a healthy life, and to persevere when life gets difficult. People who feel meaningless don’t have this motivation. They are more inclined to turn to drugs and alcohol or other hedonistic behaviors that feel good but do not help them in the long run.

The downsides involve more extreme or fundamentalist supernatural beliefs that have antisocial elements or that lead people to ignore evidence in the service of ideology. It is worth noting that this is not specific to supernatural beliefs. Secular ideologies can also take an extreme form and lead to many social problems. Consider, for instance, the mass violence and economic ruin that has resulted from communism.

KV: Recent years have seen some divisive culture clashes involving mainstream believers, secularists, scientists, religious fundamentalists, the New Atheists, New Age movements, and the like. What is your current outlook on these ongoing culture clashes? Does the “religious mind”, as you sometimes phrase it, fuel those clashes, and how can Supernatural inform those debates and controversies?

CR: I’m not sure that the religious mind fuels these clashes as much as just normal social identity and group conflict, what people often now just call tribalism. I think my book does help inform these debates by showing the ways that believers and nonbelievers are more similar than they realize. In fact, the last chapter of the book is dedicated to our common humanity. There is a lot of prejudice on all sides but humans are united by the same goals to pay our bills, find love, and be part of a community, the same hopes for our children, the same desires to live meaningful lives, and the same uncertainties and fears about death.

KV: You write in your book that you grew up in the Southern Baptist church, and that you’re the son of a father who was a missionary, pastor, and chaplain. Can you tell us about what you’ve learned from your father about religious faith, and how that background influenced your life trajectory, interests, and current thinking about these issues?

CR: Yes, I was born in and lived the early years of my life in Africa because my parents were missionaries. My father, who is no longer alive, was the most thoughtful and behaviorally consistent Christian I have ever met. Like all of us, he was human so he wasn’t perfect but he took very seriously the idea of being a follower of Christ. He was dedicated to helping the poor and the vulnerable. He believed our natural world was gift from God and acted accordingly. He was not a fan of consumerism. He never asked for much but lived a life dedicated to faith, family and community.

My life in a Christian conservative social world influenced my current thinking because many of the ideas about religion and religious people, especially conservative Christians, which I hear in the more secular liberal world of academia are completely at odds with the reality of the world I grew up in. For example, my parents were never anti-science or anti-education. Quite the opposite. My parents were never racist. Quite the opposite. Are there anti-science and racist believers? Yes, of course. But there are also anti-science and racist nonbelievers. Some of the people who I’ve met that are the most blissfully unaware of their prejudices and empirically-unsupported beliefs are secular liberal academics. Ignorance and bigotry are human, not religious, problems.

KV: Thanks Clay!

Dr. Routledge is a professor of psychology at North Dakota State University. You can learn more about him and his work at clayroutledge.com, and you can learn more about his ongoing work, his intellectual commentary on pop culture, and his public appearances and other activities on twitter at @clayroutledge.

Dr. Kenneth Vail is a professor of psychology at Cleveland State University. You can learn more about him and his work at his CSU Social Research Lab website, and you can learn more about his ongoing research and scholarly activities on twitter at @kennethvail3.