Magical Thinking

Most people don't believe in magic, but they may still wish for a good outcome by knocking on wood. Magical thinking—the need to believe that one’s hopes and desires can have an effect on how the world turns—is everywhere. Spirits, ghosts, patterns, and signs seem to be everywhere, especially if you look for them. People tend to make connections between mystical thinking and real-life events, even when it’s not rational. Of course, some of this is animistic thinking, with the belief that the supernatural is everywhere and has some power over what happens in people's lives. There is some comfort in thinking that someone or something is pulling all the cosmic strings. It gives us the permission to relax a little.

Contents

Children are primary make-believe enthusiasts, they embrace fantasies like imaginary friends with passion. This is normal in child development. This belief comes in different forms including Santa and the Tooth Fairy. Children, in addition, hold onto objects like a special stuffed toy or dirty torn blanket to help keep their fears and anxieties at bay. And shutting the bedroom closet door will definitely keep the monsters away.

Children start to believe when they are toddlers. Adults feed into their magical thinking with beliefs such as Santa, the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy, among others. As children grow older, at around age 10, they do away with fantastical play, and question how feasible magical thinking is. How can a man fly in the sky and shower every child on earth with gifts? Children may well dispense with such beliefs, but they still keep their superstitions within reach.

Researchers believe that fantastical play and magical thinking do indeed promote creative divergent thinking. One study has found that when children watched a film with magical undertones, their performance on creative tasks increased significantly when compared with children who watched a film with no references to magic.

Sometimes people look for meaning in strange places, that’s because the brain is designed to pick up on patterns. Making such connections helped our ancestors survive what they didn’t fully understand—for instance, they learned not to eat a certain kind of berry or they would die. Seeing patterns also gives an illusion of control, conferring some comfort by eliminating unwanted surprises. Humans look for superstitions, lucky numbers, coincidences, synchronicities, among other forms of thinking.

Superstitions come in many forms and they appear across cultures. In Portugal, for example, people walk backward so the devil will not know where they’re heading. In Middle Eastern countries, people hang blue colored amulets in the shape of an eye, which will ward off curses made through a malicious glare. In the U.S., people knock on wood, cross fingers, avoid crossing the path of black cats, walk under ladders, among other habits.

Everyone experiences some form of fate, some more powerful than others. For example, a person may think about a long-lost friend, one who has not come to mind for years. And then, at the same time, the bygone friend reemerges through a phone call or a text seemingly out of nowhere.

A belief that, like coincidences, life's events are not random but deeply ordered. People who believe in synchronicity see events in life as connected, and that there is no cause and effect. People feel that everything happens for a reason, that there is a grand plan, and that there is someone pulling all the cosmic strings.

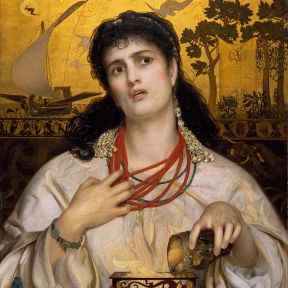

Magical thinking extends to the idea of magical contagion. It is the notion that we can pass the magic along. Hence, the reason why so many people wanted to touch Mother Theresa when in her presence. Another good example of such contagion are high-profile celebrity auctions. The estate of Marilyn Monroe auctioned off the actress's personal belongings for $13 million, and the winning bid for just one hat worn by Prince was $32,000. We’ll all take a piece of the magic.

A sugar pill can deliver powerful medicinal results. Studies show that a patient who is exposed to sham treatment (without their knowledge) can feel the alleviation of pain, as well as enjoy a boost of immunity.

Some people do seem to have all the luck, meanwhile, others who are plainly doomed never seem to get a break. However, researchers argue that the "lucky" people are just more open to new opportunities. Their personalities find the possibilities in life. They are the ones more inclined to look for patterns and coincidences.

Again, across cultures, lucky numbers will bring prosperity, good health, and other forms of success. In China, the number 8 is pronounced bah, which sounds like fah, a word that means wealth. In India, the number 9 taps love, peace, faith, among other important things. And if you play the U.S. lottery, lucky numbers seem to be 23, 11, and 9.

These practices are deployed in many domains. The eager sales representative may wear his "lucky" suit to an important meeting; and why wouldn't he if he has enjoyed prosperity again and again in that particular suit. Meanwhile, baseball players may adjust their gloves the same way before a play, or they might spit in the same spot before every pitch.

For some people, religion is filled with magical thinking. For the religious, the world is filled with spirits and ghosts and disembodied souls, and they want their higher power to hear their prayers. While atheists wonder how all that praying is working out for everyone, even atheists themselves practice habits of magical thinking, many do knock on wood just to avoid a jinx and possible catastrophe and mayhem.