Vagus Nerve

How Does "Vagusstoff" (Vagus Nerve Substance) Calm Us Down?

Vagusstoff (acetylcholine) slows heart rate via parasympathetic nervous systems.

Posted March 21, 2018

I’m on a mission to make “vagusstoff” a household word. This may sound like a bizarre quest. But, throughout my life, the visualization of squirting some vagusstoff into my nervous system by taking a deep breath followed by a long, slow exhale has been life-changing in terms of lowering anxiety and keeping me calm, cool, and collected in times of distress. Now, I want everyone to benefit from the power of diaphragmatic breathing and vagusstoff, by explaining what vagusstoff is and how it works.

Decades ago, I learned about vagusstoff from my late father, Richard Bergland, M.D. (1932-2007), who was a neuroscientist, neurosurgeon, and author of The Fabric of Mind. One of the benefits of having a father who was a neuroscientist is that he began teaching me the basics of neuroscience from a very young age using simplified terminology. Because my father was also a neurosurgeon and always on call, our one-on-one time together was sporadic — weekend tennis lessons were the only quality time we really spent together as father and son.

Like most kids, I idolized my dad. So, whenever we were alone together on the tennis court, my ears perked up. I hung on his every word. As my tennis coach, dad crammed our lessons with as much "food for thought" as possible and chose his words carefully. His goal was to optimize both my cerebellar athleticism and my cerebral intellect. Therefore, every tennis lesson was jam-packed with a mix of neuroscience and coaching advice. Esoteric phrases such as, "Chris, think about hammering and forging muscle memory into the Purkinje cells of your cerebellum with every stroke!!" were pounded into my head incessantly and became part of my vernacular.

Vagusstoff (Acetylcholine) Drives the Parasympathetic Nervous System

As an athlete, my appreciation for vagusstoff traces back to being coached by my father on the tennis court at a formative stage of my neurophysiological development. My father taught me how to hack into my nervous system by secreting vagusstoff on demand, which is an easy way to avoid choking, both on and off the court.

Whenever I was practicing my tennis serve, dad would say in a soft, soothing voice: “Chris, if you want to maintain grace under pressure, visualize squirting some vagusstoff into your nervous system by taking a deep breath — with a big inhale and a long, slow exhale (diaphragmatic breathing) — as you bounce the ball four times before every serve." To this day, I recite these words to myself in the third person whenever I play tennis, which never fails to calm me down and improve my game.

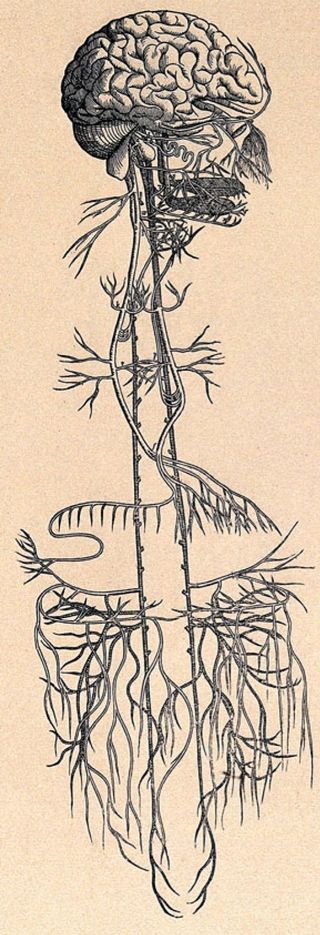

My father understood that taking a deep “belly breath” with a long, slow exhale simulates the vagus nerve to release acetylcholine, which acts like a tranquilizer within your nervous system and slows heart rate. The exhalation phase of diaphragmatic breathing squirts out vagusstoff.

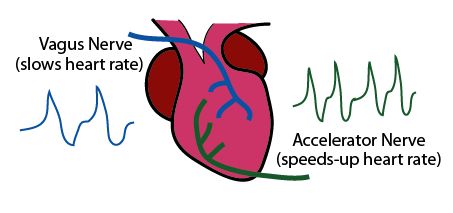

In 1921, a German Nobel Prize-winning physiologist named Otto Loewi (1873-1961) identified the very first neurotransmitter, which he coined "vagusstoff" (German for "vagus substance"). For his groundbreaking experiments on the vagus nerve, Loewi developed a simple but elegant technique of isolating a frog heart in a way that allowed him to directly stimulate the vagus nerve to “squirt out” some inhibitory vagusstoff. This action resulted in slowing down the frog's heart rate. Conversely, stimulating the accelerator nerve caused heart rate to speed up by releasing norepinephrine (adrenaline) as part of the excitatory sympathetic nervous system.

Today, vagusstoff is commonly referred to as acetylcholine. ACh is involved in a wide range of complex inhibitory functions within the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) which counterbalance the excitatory functions of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) to maintain homeostasis.

Part of Loewi’s legend is that he came up with the concept of vagusstoff in a dream. This is how Loewi described his Nobel Prize-winning eureka moment:

“The night before Easter Sunday [of 1920] I awoke, turned on the light and jotted down a few notes on a tiny slip of thin paper. Then I fell asleep again. It occurred to me at 6.00 o’clock in the morning that during the night I had written down something important, but I was unable to decipher the scrawl. The next night, at 3.00 o’clock, the idea returned. It was the design of an experiment to determine whether or not the hypothesis of chemical transmission that I had uttered 17 years ago was correct. I got up immediately, went to the laboratory, and performed a simple experiment on a frog heart according to the nocturnal design.

On mature consideration, in the cold light of the morning, I would not have done it. After all, it was an unlikely enough assumption that the vagus should secrete an inhibitory substance; it was still more unlikely that a chemical substance that was supposed to be effective at very close range between nerve terminal and muscle be secreted in such large amounts that it would spill over and, after being diluted by the perfusion fluid, still be able to inhibit another heart.”

“Vagusstoff” is a shorthand term anyone can use to sum up the more complex process of engaging the parasympathetic nervous system via the vagus nerve to inhibit "fight-or-flight" stress responses.

The Relaxation Response Counterbalances Fight-or-Flight Stress Responses

One of my mentors in life, Herbert Benson, is a legendary trailblazer who has taught millions of people around the globe how to activate the parasympathetic nervous system and counteract fight-or-flight stress responses. In 1975, Benson published his best-selling, game-changing book, "The Relaxation Response."

In the 1960s, Dr. Benson realized that patients get nervous when they visit the doctor's office. Their anxiety triggered a sympathetic fight-or-flight response that raised blood pressure and heart rate, which made it difficult to get accurate readings. Because of this conundrum, Benson took an interest in how meditation techniques might calm the nervous system on demand.

In the decades since that initial epiphany, Benson has played a pivotal role in legitimizing the health benefits of mind-body interventions (MBIs) in the eyes of Western medicine practitioners. The Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Harvard's Massachusetts General Hospital continues to be a 21st-century pioneer of mind-body research and everyday application.

In the 1970s, my father was chief of neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School's Beth Israel Hospital and colleagues with Herb Benson, who was a cardiologist at the "B.I." during this time. Because of this synergy and overhearing countless dinner party conversations about mind-body medicine when I was a kid, concepts of vagusstoff and the relaxation response have always been conjoined in my mind.

Over the past few years, I've been expanding on Benson's concept of "The Relaxation Response" by combining my lifelong experience of purposely engaging the vagus nerve to release vagusstoff with state-of-the-art clinical research on heart rate variability.

HRV is a common marker used to indicate parasympathetic nervous system activity and the secretion of vagusstoff to slow heart rate in-between beats. Higher HRV is an index for healthy parasympathetic activity, robust vagal tone, physical fitness, and overall wellbeing.

In recent months, I've curated a wide range of lifestyle behaviors (in addition to meditation and diaphragmatic breathing) that counteract "fight, flight, or freeze" stress responses and improve HRV by hacking the vagus nerve.

For more, see "A Vagus Nerve Survival Guide to Combat Fight or Flight Responses" and "Vagus Nerve Facilitates Guts, Wits, and Grace Under Pressure."

References

Alli N McCoy and Yong Siang Tan. "Otto Loewi (1873–1961): Dreamer and Nobel Laureate" Singapore Medical Journal (2014) DOI: 10.11622/smedj.2014002