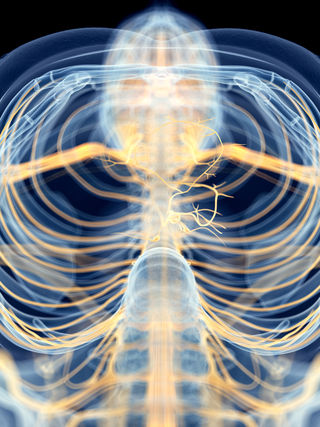

Vagus Nerve

Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises and Your Vagus Nerve

Vagus Nerve Survival Guide: Phase One (This entry is first in a 9-part series.)

Posted May 16, 2017 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

This Psychology Today blog post is phase one of a nine-part series called "The Vagus Nerve Survival Guide." The nine vagal maneuvers featured in each of these blog posts are designed to help you stimulate your vagus nerve—which can reduce stress, anxiety, anger, and inflammation by activating the "relaxation response" of your parasympathetic nervous system.

Diaphragmatic breathing (also referred to as "slow abdominal breathing") is something you can do anytime and anywhere to instantly stimulate your vagus nerve and lower stress responses associated with "fight-or-flight" mechanisms. Deep breathing also improves heart rate variability (HRV), which is the measurement of variations within beat-to-beat intervals.

For millennia, yogis and sages from Eastern cultures have understood the importance of diaphragmatic breathing. Since the 1970s, the trailblazing efforts of mind-body thought leaders such as Herbert Benson and Jon Kabat-Zinn have popularized the paramount importance of deep breathing as a central component of maintaining a healthy physiological balance (homeostasis) within your autonomic nervous system, which is widely accepted by "Western medicine" practitioners today.

In 2010, an international study reaffirmed this timeless wisdom by showing that slow abdominal breathing reduced the "fight-or-flight" response of the sympathetic nervous system and could enhance vagal activity. These findings were published in The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine.

In 2014, Paul M. Lehrer and Richard Gevirtz (who is a pioneer in HRV research and training) published a hypothesis and theory paper, "Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback: How and Why Does it Work?" in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

In this review, Lehrer and Gevirtz explore a wide range of fascinating reasons that HRV biofeedback works and reaffirm that diaphragmatic breathing is part of a feedback loop that improves vagal tone by stimulating the relaxation response of the parasympathetic nervous system. Notably, the researchers also report that people with a higher HRV (which represents healthy vagal tone) showed lower biomarkers for stress, increased psychological and physical resilience, as well as better cognitive function.

In 2016, another study reported that slow abdominal breathing improved the autonomic sympathovagal modulation (which minimizes the "fight-or-flight" response) and was highly effective at reducing the stress-related cardiovascular response in prehypertensive "stressed out" college students.

The last study I'm going to reference in this post examines the flip side of having lower heart rate variability as observed in veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In 2015, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System reported that reduced HRV may be a contributing risk factor for PTSD. These findings were reported in the journal JAMA Psychiatry. In this study, the researchers found that U.S. Marines with lower HRV prior to deployment displayed higher vulnerability to PTSD after they had returned. The good news is that anyone with PTSD can use holistic vagal maneuvers and/or vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) devices to improve his or her HRV.

"What Type of Diaphragmatic Exercises and Technique Should I Use?"

When it comes to effective vagal maneuvers, any type of deep, slow diaphragmatic breathing—during which you visualize filling up the lower part of your lungs just above your belly button like a balloon...and then exhaling slowly—is going to stimulate your vagus nerve, activate your parasympathetic nervous system, and improve your HRV.

Some people make time every day to practice diaphragmatic breathing as part of a yoga or mindfulness-meditation routine. Others only take a really deep breath anytime they catch themselves feeling "panicky," need to have grace under pressure, or want to relieve some frustration. All of these applications of diaphragmatic breathing can reap huge benefits.

Some diaphragmatic breathing techniques prescribe inhaling and exhaling only via mouth breathing. Other experts recommend breathing only through your nose. I generally like to use a combination of both. Again, I'd suggest doing whatever type of diaphragmatic breathing fits your lifestyle and feels right.

Anecdotally, what's worked best for me over the years is an easy technique I cobbled together, in which I inhale very slowly through my nose, while consciously filling up my lungs from the bottom to the top until I can't suck in an iota more of oxygen. Then, I slowly begin releasing the air through pursed lips as if I'm trying to systematically blow out 100 candles on a birthday cake, while constricting my abs as if I'm doing an abdominal crunch. Sometimes, I hold my hand up to my lips to feel the air being released.

Generally, when I'm stressed out and really need to do some deep breathing, I'm also in a rush and don't have the time to focus on an extended diaphragmatic or "yogic" breathing session. Of course, any time most of us need to create the relaxation response, we're also least likely to have the peace of mind and spare time to actually take a few deep breaths.

So, when it comes to my daily diaphragmatic breathing routine, I set the bar very low and say in a third person drill sergeant voice to myself, "Chris, this is only going to take a few seconds. Do three cycles of diaphragmatic breathing right now!" Then, I'll do the diaphragmatic breathing technique I described above of inhaling through my nose and exhaling through pursed lips for a total of three in-out cycles. This only takes about 60 seconds and can be done anytime, anywhere.

Hopefully, the clinical evidence and practical advice on using diaphragmatic breathing exercises to stimulate your vagus nerve presented herein will be of some use to you. As I mentioned earlier, this Psychology Today blog post is "phase one" of a nine-part "Vagus Nerve Survival Guide" series. Please stay tuned for upcoming posts.

References

Shu-Zhen Wang, Sha Li, Xiao-Yang Xu, Gui-Ping Lin, Li Shao, Yan Zhao, and Ting Huai Wang. Effect of slow abdominal breathing combined with biofeedback on blood pressure and heart rate variability in prehypertension. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. October 2010, 16(10): 1039-1045. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0577

Paul M. Lehrer and Richard Gevirtz. Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology. July 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

S Chen, P Sun, S Wang, G Lin and T Wang. Effects of heart rate variability biofeedback on cardiovascular responses and autonomic sympathovagal modulation following stressor tasks in prehypertensives. Journal of Human Hypertension. February 2016. doi:10.1038/jhh.2015.27

Arpi Minassian, Adam X. Maihofer, Dewleen G. Baker, Caroline M. Nievergelt, Mark A. Geyer, Victoria B. Risbrough. Association of Predeployment Heart Rate Variability With Risk of Postdeployment Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Active-Duty Marines. JAMA Psychiatry, 2015; 1 DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0922