Health

The Dangers of the “Learning Loss” Craze

Mental health problems may soar after COVID if kids are pressured to achieve.

Posted June 4, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Childhood suicidality and depression were at alarming levels well before COVID.

- Now that the pandemic is easing, measures to combat "learning loss" may further exacerbate mental health problems.

- Children's need for down time, socialization, and access to mental health services should take priority over arbitrary curricula.

As the pandemic wanes, a trend emerges in K-12 education which I fear both masks and rationalizes the unnecessary challenges to children’s mental health looming on the horizon. If left to take its course, we could be looking at a new wave of childhood depression, anxiety, and even suicide. However, I also believe this can be avoided if we have the courage to value our children’s mental health more than their achievement.

At a time when our kids’ wellbeing should be first and foremost on the mind of educators and parents alike, we would expect the efforts of the education system to be focused on increasing mental health services, getting children back to socializing, reestablishing stability, and helping them process the impact of the pandemic and the political conflicts which have permeated our entire society. But instead, too many conversations are centered on getting children “caught up” with content they missed while they were busy experiencing these traumas. Of course, what this likely means is more pressure to achieve; it may ultimately lead to longer school days, an extended instructional year, and extra homework.

As is often the case, this pressure to achieve is clad in the veil of compassion and euphemized as concern over “learning loss.” What the learning loss craze actually represents is a systematic ratcheting up of stress at the worst possible moment when kids are most vulnerable.

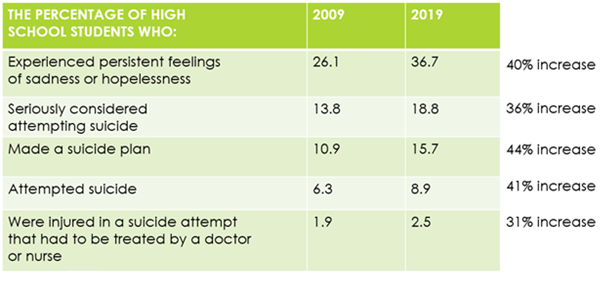

To understand where children’s stress levels are at, let’s first look at how the stage was already set for a childhood depression epidemic even before the advent of COVID-19. As you can see in the below table with the most recent comprehensive data from the Centers for Disease Control (2020), from 2009 to 2019, children experienced alarming increases in depression and suicidality, with over a third of all high school children experiencing persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. The number of these children who had attempted suicide was already so high that in a class of 30 kids, it’s a safe bet that 2 or 3 have tried to end their own lives. Put another way, if you are a parent, there is nearly a 10 percent chance that your child’s life will be threatened by this potentially fatal danger. Again, this is before the pandemic hit.

We can only begin to evaluate the pandemic’s impact on children’s mental health. But those of us in the field are watching closely as studies trickle out. A very informative yet accessible overview of what we know so far was recently published in the New York Times by researcher Emily Esfahani Smith (2021). Rather than attempt a similar summary here, I’ll simply refer the readers to the piece. But suffice it to say for our purposes, the outlook is grim regarding how the pandemic further exacerbated pediatric mental conditions from their already-shocking pre-COVID levels.

One of the mentioned early studies (Luthar et al., 2020) found that in the immediate wake of the pandemic, children’s mental health actually improved. The detriments of losing their cherished freedom and opportunities to socialize with friends were outweighed by the benefits of a respite from school stress. I want to take a moment to pause here to allow the reader to fully appreciate the gravity of this finding and its implications. I ask you: What kind of society have we created where a pandemic is an improvement to our children’s quality of life?

In this bleak landscape of childhood distress, we're now seeing a growing obsession with learning loss. I’m here to suggest this exactly the wrong conversation at exactly the wrong time. Children being several months “behind” arbitrary academic expectations is not a crisis. This increase in childhood depression is.

If we desire a society that is simultaneously both compassionate and rational, we must regard mental health challenges with the same seriousness and gravity as threats to our physical wellbeing. When confronted with COVID, which has infected about 10 percent of the adult population (CDC, 2021), we wisely acted with caution and shut the whole country down. We mobilized to pour billions into remedial measures.

And as we slowly return to normalcy, we are not advising, for example, that businesses plan on opening to twice as many customers as usual to make up for lost income. Far from it. We can easily recognize that such action would directly counteract the very progress we need to make. Instead, we are taking a gradual approach that prioritizes our physical well-being as the central factor driving decisions.

Just as about 1 in 10 adults has experienced COVID, nearly 1 in 10 high school children has attempted suicide. For me, these represent comparable crises. So I wonder why we don’t react to this pandemic of despair with the same concern. Or failing that, I wonder why we are tempted to take the exact opposite approach and throw proverbial fuel on the fire by exacerbating the very stressors which have caused the problem to begin with. I’m personally left with the sad conclusion that we as a society are not recognizing parity between mental and physical health and we’re also not recognizing that children are equal human beings with equal human rights.

But while I think it’s critical to acknowledge these difficult facts, I come back to where there is hope and what is within our power to change. My own suggestion is this: If you are a parent meeting with educators to discuss learning loss, set a timer to divide the meeting equally into two halves. Let them know that for the first half, you want to discuss only mental health concerns. Parents can discuss their children specifically or simply ask questions to hold the school accountable for the other kids.

Ask questions like: Are there mental health counselors at the school? How many? Are these permanent positions? What are their professional credentials? What is the counselor-to-student ratio? How do they identify students in need of counseling? What is the process for a child or family who wants to initiate counseling? What types of services are available? What happens if a student needs a higher level of mental health care than the school can provide? What trainings do teachers receive on mental health issues? What trainings are available for parents? Students? How often are these training held? How is the school working to prevent suicide? This is just a start, but I think you get the point.

If you are a teacher or educator, you can go above and beyond by proactively introducing this structure in your interactions with parents and ensuring faculty meetings are divided equally between social/emotional and academic issues. We say the goal of education is to address the whole child, so let’s make that mean something.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2009-2019. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBSDataSummaryTrendsRep…

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). CDC COVID Data Tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days.

Smith, E. E. (2021, May 4). Teenagers Are Struggling, and It's Not Just Lockdown. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/04/opinion/coronavirus-mental-health-te….

Luthar, S. S., Ebbert, A. M., & Kumar, N. L. (2020). Risk and resilience during COVID-19: A new study in the Zigler paradigm of developmental science. Development and Psychopathology, 33(2), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579420001388