Cognitive Dissonance

It's So Bad: Cognitive Dissonance and Cheap Games

Are you more likely to enjoy a video game bought at full price or on sale?

Posted August 21, 2013

All else being equal, do you enjoy the games you pay full price for as much as the ones you buy on sale for cheap? While it of course first depends on the game, a certain well known theory in psychology suggests that paying $60 for the new Tomb Raider game when it came out last March, for example, might lead to your enjoying it more than waiting to buy it for $15 for it a few months later.

Back around 1959, Leon Festinger and one of his ambitious undergraduate students, Merrill Carlsmith, conducted an experiment at Stanford University. For an hour straight, the subjects carefully removed and replaced a bunch wooden spools from a tray over and over again and meticulously twisted rows and rows of wooden dowels on a rack. It was, in other words, a stupefyingly boring series of tasks.2

For an hour they had to do this. But at the end of the experiment, the researcher pretended to be in a bind, saying that he needed someone to describe the task to the next subject waiting to take his turn at the boring tasks. But the thing is that the subject had to really sell the tasks and make them sound super fun and interesting –a service for which the researcher offered to pay. Depending on which experimental condition the subject was in, he was offered either $20 or $1.

Subjects then went and met with the person who they thought was the next subject, but who was really another experimenter who prompted the subject to explain what was so great about what they were going to be doing. The subjects then dutifully lied through smiling teeth about how much fun the tasks were going to be. Boy howdy! Twisting knobs! SO MUCH FUN, MAC!3 Then, some time later, the subjects were asked to fill out a form and rate how enjoyable the boring spool moving and knob twisting tasks really were.

The results? Those who had been paid $1 to lie about the tasks rated them as more fun than those who had been paid $20. Festinger and Carlsmith theorized that this was because of what they called cognitive dissonance, which is a state of mental tension brought on by holding two contradictory thoughts at the same time. People are motivated, the researchers said, to eliminate this tension by abandoning or changing one of the thoughts.

In the case of the experimental subjects who were paid a paltry $1 to slump their shoulders and lie, the two incompatible thoughts were:

- Man, those tasks were f’ing boring.

- I was willing to lie to a fellow student for next to nothing.

Subjects were unable to do anything #2, but Festinger argued that they were able to remove the cognitive dissonance by deluding themselves that #1 wasn’t true. Thus, they really did think that the tasks were enjoyable.

What about those in the $20 condition, you ask? Good question. Festinger argued that $20 was quite a bit of money –in the 1950s, $20 could buy as much as $150 could buy today, and these were college students. Those subjects were able to convince themselves that this bribe was sufficient reason for them to lie. “Those tasks were boring” and “I was paid a huge wad of cash to tell a lie” did not necessarily create much cognitive dissonance.Perhaps, at most, it would get them to insert “harmless” before "lie."

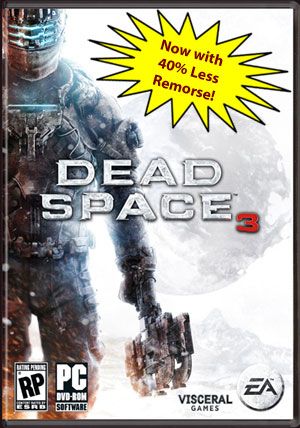

So with this in mind, let’s get back to video games. Earlier this year I bought the new Simcity game. Unfortunately it was so wrought with bugs, server problems, and broken promises that publisher Electronic Arts offered customers a free game on which to gnash their teeth. With my credit, I chose Dead Space 3. I thought this was a pretty awesome deal, since the game had been selling for a full $60 just a few weeks earlier. I was getting it for free.

Now, I really liked the first two Dead Space games, but after just a few hours of tromping through another space station fighting more necromorphs, I felt completely bored. I didn’t like it. I stopped playing.

This made me think about the subjects in Festinger’s experiment, and whether or not I might be feeling the lack of cognitive dissonance. Or more to the point, if I had paid $60 for Dead Space 3, would I have convinced myself that I was enjoying it, rather than face the fact that I had decided to spend all that money on a full priced game? Even worse, would I have gone online to tell people who didn’t like the game that they were wrong and that all their arguments were invalid?

Probably. A little, at least. Research on cognitive dissonance theory and consumer choice exploded4 in the 1970s and researchers found that shoppers were generally willing to change their attitudes towards purchases in order to confirm their belief that they were worth the price –and vice versa.5 Researchers have also found that cognitive dissonance after purchases (a.k.a., “buyer’s remorse”) can be reduced by getting directly involved with the purchasing decision (as opposed to just following the advice of marketing material or salespeople) and taking more time to make the decision.6 Probably because shoppers can more easily convince themselves that they were well informed and not duped.

In the case of full priced video games, “I thought this was worth spending $60 on” and “I’m not liking it” are bound to cause some mental tension. Absent generous return policies, you can’t do much about having paid full price for a game. But it’s comparatively easy to convince yourself that you’re enjoying it more.

C’mon, admit it. I’m not the only one. You’ve done this before, haven’t you?

[Want to see more stuff like this article? Follow me on Twitter: @JamieMadigan]