Bipolar Disorder

Are Positive and Negative Emotions Really Opposites?

The link between positive and negative feelings is not so clear-cut.

Posted February 10, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Imagine that you are a clinician who delivers psychological treatment to depressed clients. Would you be able to alleviate the prolonged sadness of your clients by “prescribing” them high doses of positive emotion, or would such a treatment be ineffective?

Your evaluation of the usefulness of this intervention will depend on your perception of the relationship between positive and negative feelings. Do you consider positive and negative feelings to be polar opposites, with decreases in negative emotions going hand in hand with increases in positive emotions (and vice versa)? Or do you believe that positive and negative feelings make up two separate dimensions, operating independently from each other?

How positive and negative feelings relate in everyday human experience is anything but trivial. Like the thought experiment illustrates, the answer to this question has real-life consequences. Not surprisingly, this issue has been a topic of long and intense debate, with some scholars proposing a single bipolar continuum for positive and negative feelings (e.g., Russell & Carrroll, 1999), while others have claimed that positive and negative feelings are two independent dimensions (e.g., Watson & Tellegen, 1985).

The initial debate

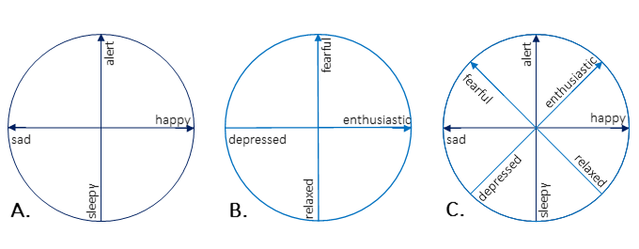

Regarding theories that hypothesize a bipolar relation between positive and negative emotions, the most influential model is probably the circumplex model of affect proposed by Russell (1980). According to this framework, every emotional experience may be located in an affective space that is delineated by two irreducible dimensions: valence and arousal (see Figure 1, Panel A, below).

The valence dimension is a bipolar continuum that captures the hedonic quality of an emotion, ranging from feeling pleasant to unpleasant. Positive (e.g., happy) and negative feelings (e.g., sad) are thus considered diametric opposites, with increases in sadness going hand in hand with decreases in happiness, and vice versa. Russell and colleagues find evidence for a bipolar relation in several cultures, various age groups, and different emotional components (e.g., subjective experience versus facial expressions). Second, the arousal dimension intersects the valance axis and captures the degree of activation associated with an emotion, ranging from feeling sleepy to being highly alert. In this way, the core of each emotional experience is conceptualized as a unique blend of these two dimensions, with the emotion of anger, for example, being negatively valenced and high in arousal, while feeling relaxed is positively valenced and low in arousal.

In contrast, with respect to theories that assume an independent relation between positive and negative emotion, the work of Watson and Tellegen (1985) can be considered the most influential. Similarly, these authors consider our affective world to be composed of two underlying factors, yet they argue that positive (e.g., enthusiastic) and negative feelings (e.g., fearful) each comprise their own separate dimension (see Figure 1, Panel B). Positive and negative feelings are believed to operate independently from each other, with changes in positive feelings informing us little about changes in negative ones, and vice versa. Also, these authors find evidence for their claim. In personality psychology, for example, the experience of positive feelings is known to show a unique relation with extraversion and reward sensitivity, while negative feelings are independently associated with being emotionally unstable (neuroticism) and reactivity to punishment.

A more nuanced picture

Which theory has stood the test of time and represents reality best? Although both the bipolar and independent research lines were able to provide empirical evidence for their own view, as is often the case with scientific research, the answer to this question is: it depends.

It has been argued that both conceptualizations in fact approach the same affective space from a different angle (more specifically a 45° rotation, see Figure 1, Panel C). The two independent axes in Watson and Tellegen’s two-factor model are essentially a blend of valence and arousal. To capture this nuance, these authors later termed their dimensions positive and negative activation. The positive and negative activation axes do therefore not provide evidence against a bipolar valence dimension. Instead, different positive and negative emotion words differ in the degree of bipolarity they exhibit (e.g., the extent to which they are truly opposites).

Research has also demonstrated that the extent to which positive and negative emotions are independent versus bipolar may vary with a multitude of factors, further helping to reconcile both seemingly opposing viewpoints. For example, whether you evaluate people’s positive and negative emotions over a long versus short time span is known to impact their mutual relation. Similarly, whether you assess their intensity (e.g., how sad were you today?) versus frequency (e.g., how many moments of sadness did you experience today?) will change your conclusions.

Finally, recent research shows that the relation between positive and negative feelings may not be the same for everyone. While some individuals generally experience positive and negative emotions relatively independently, other individuals experience these affective states more as bipolar opposites. Furthermore, even within the same individual, there may be moments or situations in which positive and negative feelings are mutually exclusive, while at other times these affective states may co-exist. As a consequence, in contrast to what these earlier models assumed, the relation between positive affect is neither universal nor fixed.

Individual differences in the relation between positive and negative feelings

Why are positive and negative affect relatively independent for some, but mutually exclusive for others? In a recent series of studies (Dejonckheere et al., 2018a; Dejonckheere et al., 2018b), we observed that the degree to which people experience affect as bipolar versus more independent is indicative of their psychological well-being, and in particular, the extent to which they suffer from depressive symptoms.

To chart these individual differences, we rely on experience sampling research. In this data collection method, researchers instruct participants to carry a smartphone throughout their everyday lives and ask them to report on their momentary experience of various positive and negative emotions multiple times per day. In three studies, we observed how people who had higher depressive symptom severity showed a more inverse relation between positive and negative feelings. For these individuals, the experience of negative affect ruled out the experience of positive affect, and vice versa. In contrast, people without depressive symptoms experienced positive and negative feelings more independently. For these individuals, there were many moments or situations where positive and negative emotions could separately co-exist.

What is the reason for this finding? In a follow-up study, we aimed to get a better understanding of the relation between depressive symptoms and affective bipolarity. We established that people who suffer from depressive symptoms often experience difficulties with regulating their emotions in stressful situations. Indeed, depressed people are more easily overwhelmed when confronted with distressing information.

Evolutionary theories argue that when we are under a lot of stress, a fine-grained and detailed processing of our environment is no longer adaptive, as this would overburden our cognitive system (see Figure 2). To survive in stressful environments, a quick-and-dirty approach is preferred, favoring heuristic judgments over rigorous consideration.

Applying this to our emotional world, when experiencing a lot of stress, processing positive and negative emotional information in parallel may be too burdensome. In these circumstances, these theories argue, it is better to pursue emotional simplification, fusing positive and negative affect to be a single dimension.

Because depressed individuals experience a lot of distress, have cognitive difficulties, and find it hard to adequately regulate their emotions, these theories may help us understand why depression is characterized by an affective world that is more unidimensional.

Finally, it is evident that affective bipolarity may constitute an important maintaining mechanism in people who suffer from depression. Since depressed individuals typically lack a buffer of positive feelings when experiencing high levels of negative affect, this could lead to a cycle of prolonged dysphoria and anhedonia (i.e., the inability to experience pleasure or enjoyment). As the depression gets worse, negative feelings may increasingly rule out the experience of positive ones, locking people in a downward spiral of negativity. Following this rationale, therapeutic interventions that effectively counteract the experience of negative feelings with positive ones could break this debilitating cycle.

Change over time in the relation between positive and negative feelings

Research also shows that the relation between positive and negative affect is not the same across time. That is, at one moment in time a person may process positive and negative emotions independently, while at other moments he or she may have a more bipolar experience of these affective states.

When everything is normal and no particularly important events or situations color our lives, we are likely to experience positive and negative emotions independently. However, when one meaningful event or situation becomes more central in our life, our affective system will be pushed towards bipolarity. For example, in a recent study (Dejonckheere et al., 2019), when we tracked students’ positive and negative emotions around the time they would receive their exam results (an event with major personal implications), we observed how their affective experience became increasingly bipolar in anticipation of this event. As time after this event dissipated, however, and this event lost its central place in the students’ lives, the experience of positive and negative affect became more independent again.

The underlying idea is that these context-dependent fluctuations in the relation between positive and negative affect may be adaptive. That is, a flexible affective system that switches from independence to stronger bipolarity could function as an emotional compass that draws our focus to personally significant information, as it signals the activation of a concern or event we consider important.

A unidimensional emotional life—which generates an affective experience that is either positive or negative—directly communicates whether our personal interests and concerns are met or not. In turn, this emotional evaluation may instigate a motivational push that guides our thoughts and behavior to respond to that information in an appropriate way. However, if our emotional system gets stuck in an either/or way of affective processing, it loses this adaptive function, and may indicate impaired mental health.

Conclusion

In sum, research suggests that the link between positive and negative feelings is not as straightforward as traditional theories assumed. Recent studies present a more nuanced picture of the relation between positive and negative affect, establishing differences between people as well as changes over time.

(Parts of this blog post appeared in Egon Dejonckheere’s doctoral thesis.)

References

Dejonckheere, E., Kalokerinos, E. K., Bastian, B., & Kuppens, P. (2018b). Poor emotion regulation ability mediates the link between depressive symptoms and affective bipolarity. Cognition and Emotion, 1–8.

Dejonckheere, E., Mestdagh, M., Houben, M., Erbas, Y., Pe, M., Koval, P., … Kuppens, P. (2018a). The bipolarity of affect and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 323–341.

Dejonckheere, E., Mestdagh, M. Verdonck, S., Lafit, G., Ceulemans, E., Bastian, B., & Kalokerinos, E., (2019). The relation between positive and negative affect becomes more negative in response to personally relevant events. Emotion, Advanced online publication.

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178.

Russell, J. A., & Carroll, J. M. (1999). On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 3–30.

Watson, D.,& Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 219–235.