Magical Thinking

She Loves Me, She Loves Me Not

When only a magical roll of the dice will do.

Posted September 6, 2013

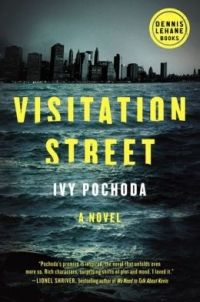

One of the great pleasures of my summer was reading Ivy Pochoda’s new novel, Visitation Street. [Disclosure: Ivy Pochoda is a friend of mine, and my assessment of her work is far from objective. But you don’t have to take my word for it.] It is summer in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn, and two young girls are bored. Val convinces June to take a small raft out into the bay on an ill-fated voyage from which only Val returns, washed up on the beach. As time passes and Val’s feelings of guilt increase, she employs a number of superstitions in the hope of bringing her friend back.

These moments of the novel were particularly intriguing for me because they involved a form of magical thinking that is rarely documented by anthropologists or folklorists and almost never discussed by psychologists. A kind of superstition that I had all but forgotten about. In one scene, Val is in church and imagines that if she can predict “the precise moment, counting by ten, when the priest will close his hymnal, June will walk into the church and all will be over” (p. 86). In another case she adopts the belief that, if she can get the girls at her school to like her, June will come home.

Val’s wishful fantasies are examples of personal superstitions, magical beliefs that are unique to the user and distinct from the socially shared superstitions with which we are all familiar: black cats, the number thirteen, and rabbits’ feet. Personal superstitions include lucky pieces of jewelry or items of clothing and rituals performed before a game or an important event. When I came across these points in the novel, I was reminded of a number of endearing rituals that children and adults employ to bring good luck. For the boys of my youth, a common equivalent was to wad up a piece of paper and claim that, if you were able to make a shot into the wastepaper basket across the room, a new bike or some other desired thing would magically appear. I can remember engaging in both the wastebasket game and other imagined bargains like Val’s.

Only one step removed from these luck-enhancing mind games are various fortune-telling devices that people employ when they are hoping for something good. People who have their eyes on a new romantic partner will pull the petals off daisies while reciting the familiar refrain, “She loves me. She loves me not….” Young children play with popular “cootie catcher” fortune tellers made of folded paper. The game can be played in a variety of ways, but the device is typically manipulated a prescribed number of times to determine which of the inner flaps containing a message of good or bad fortune is yours to uncover.

An elaborate cootie catcher.

The target of all superstitions is some goal that is important to us but uncertain. If we are sure we can get what we want, there is no need for superstition, and similarly, if we don’t really care about the outcome, there is no motivation to be superstitious. But when we care deeply about something and yet we cannot be sure it will appear—or, in the case of negative events, be avoided—superstitions are sometimes used to curb anxiety and give a sense of increased hopefulness.

In the case of typical superstitions, the talisman or ritual is used to decrease uncertainty about a specific, focused event. The actor keeps a lucky stone in her pocket during a performance in an effort to avoid calamity. The student wears a lucky sweater to the final exam to bring on a good grade. But in the case of Val’s magical bargains or the gamble about a shot at the wastepaper basket, the status quo is the thing we hope to shake up. There is no specific up-coming event at which the superstition is aimed. Instead, we would be happy almost any time the object of desire (the reappearance of Val’s friend June, a new bike) materialized, and we are willing to take our chances on a magical gamble to get what we want. Of course, we pay nothing to play these wishful games. If anything, we risk a small additional bit of disappointment. Nonetheless, this is an unusual form of magical thinking. Normally we do everything we can to eliminate uncertainty in our lives, but sometimes, when we see no other way to control the situation, a magical roll of the dice can be just the thing we are looking for.