Education

How Should We Talk to Kids About Death?

Child advocates use fiction to guide parents on an effective approach.

Updated July 8, 2023 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Children’s questions about death can put parents on the spot.

- Stories that show such a discussion can help children to understand.

- Age-appropriate stories offer parents and kids a common language for tough subjects.

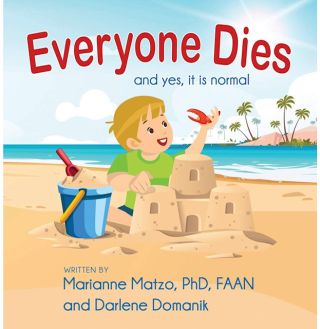

A boy named Jax walking on the beach with his grandfather spotted a crab leg. He asked what had happened to the crab. His query inspired a children’s book, Everyone Dies, and Yes, It Is Normal. The story about Jax's curiosity and his grandfather's response shows how to discuss the subject of death with young children in a natural, positive manner.

Author Marianne Matzo, a certified nurse practitioner in oncology and palliative care, has a Ph.D. in gerontology. She spent over four decades assisting people who had incurable illnesses to manage their pain. Her focus now is on community education via a successful podcast at every1dies.org that covers a range of topics like advance directives, how to write condolence notes, and the definition of a good death. “Our focus is public education related to life limiting illness, dying, death, and bereavement,” Marianne said.

Her co-author, Darlene Domanik, is a retired environmental lawyer and childcare advocate who has owned and managed two childcare facilities. She also teaches meditation. Her part was to develop the fictional aspect in a way she thought young children could understand.

The book is intended for kids up to age 10. I asked these co-authors to discuss their reasons for writing it.

“The model for talking with children about death is one that I have used in my clinical practice as a nurse practitioner, as well as with my own children,” Marianne said. “There are only three reasons people die, and children need a concrete language to understand why a person or animal is dead. ‘Grandma died because she was very very sick or very very old or very very hurt.’ Kids get that. And they will use the language themselves. My girls are 26 and 27, and to this day if I say someone is sick, they ask if they are very very sick.”

Darlene acknowledged this and added another aspect. “We wanted to tell a story that a child and an adult would enjoy. A day at the beach is fun! The setting and conversations are not at all frightening and allow the story to unfold naturally. It was also important that we have a ‘happy ending.’ We considered this very carefully, and consulted with a PhD in child psychology. Just about every other book addressing the subject of death for small children does a cutesy thing with the spirit of the dead person, e.g. ‘Grandma is a star watching over you,’ or ‘Grandpa is now in the flowers, trees and butterflies and will be with you always.’ We think issues of spirituality and religion are best left to parents. Our book works as a starting point. Religious and nonreligious alike appreciate this approach and understand that it is, ultimately, respectful. Further, very young children rarely ask what happens after death. Such philosophical questions occur at a later stage of development. Toddlers are quite simple and concrete in their thinking.”

Although older children have also responded to the book, the authors are considering a second one aimed more specifically at school-age kids.

“This will be a chapter book and a much more difficult project," Darlene stated. "In order to hold the interest of a school-aged reader, the story will have to include adventure, conflict, mystery, and humor. The protagonist will be a heroic underdog.”

Pediatric physician David Schonfeld warns that limiting discussions about death could interfere with the child’s ability to cope when it happens to someone they know. They might experience guilt, shame, fear, or even “view death as a form of punishment.” Kids need to be able to talk about it. Placing the concept into a story frame like Everyone Dies, with a natural setting that works within the cognitive parameters of young children, can help them to express their feelings and concerns.

References

Matzo, M. & Domanik, D. (2021). Everyone dies, and yes, it is normal. Vanitas Press.

Schonfeld, D. (1993). Talking with children about death. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 7(6), 269-74.