Attention

The Bright Side of Uncertainty

How can our negative capabilities help us embrace uncertainty?

Posted November 18, 2012

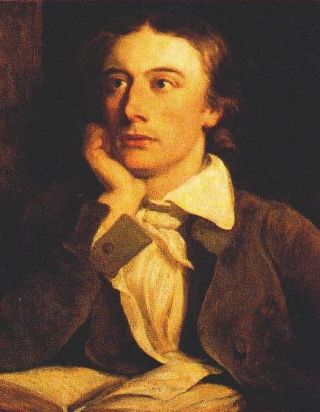

In 1817, the poet John Keats wrote to his brothers to discuss the value of being open to uncertainty, mystery, and doubt. In his letter, he offered a critique to those he saw as attempting to categorize all human experience into a theory of knowledge. He criticized Coleridge, whom he viewed as seeking knowledge over beauty. Keats used the phrase, negative capability, to describe an openness to experience without the need to rationalize, categorize, or in any sense analyze what is happening. He wrote:

I had not a dispute but a disquisition, with Dilke on various subjects; several things dove-tailed in my mind, and at once it struck me what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, especially in Literature, and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously — I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason — Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge. This pursued through volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

Keats later wrote that, “what the imagination seizes as beauty must be truth.” He was preoccupied with our infatuation with truth-seeking and epistemology-making and the possibility that we miss the sublime, even uncanny “truth” of our experience in our fruitless search for essentials. Though writing about art, Keats seemed to be getting at something worth considering as a kind of psychological virtue or tool.

What would it mean to be capable of bearing uncertainty, doubt, and mystery–without any “irritable reaching after fact and reason?” If this was a psychological capacity, would it be valuable? Is there a bright side to uncertainty and, if so, would we want more of it? Are there unseen pleasures with being bewildered?

In her wonderfully introspective study, A Life of One’s Own, the psychoanalyst Marion Milner embarked on a seven year personal journey to understand what brought her joy, fulfillment and happiness. Extracting the data of daily life from her diary, she became a kind of detective in coming up with rules that would lead to each day’s “catch of happiness.” Originally published in 1934, Milner’s book was a preface to the much more recent science of positive psychology. Among several so-called rules she discovered was the idea that there were two modes we use to perceive the world around us: narrow attention and wide attention. In her view, we could shift from narrow to wide attention with a simple act of will and this shift would “make boredom and weariness blossom into immeasurable contentment.”

Wide attention seems like another way of talking about negative capability. For Milner, we spend much of our days with a narrow focus. This is our largely automatic way of attending to daily affairs. We attend to what serves our immediate interests and we ignore the rest. Milner compared narrow attention to “a ‘questing beast,’ keeping its nose close down to the trail, running this way and that upon the scent, but blind to the wider surroundings.” Since everything is a means to an end, contentment is always located in the future. When we’re narrowly attentive, we look for what brings us happiness and contentment and, presumably, do more of it. It is happiness by following a recipe. With wide attention, we attend to something, yet want nothing from it. Nothing is privileged. With no analytic agenda, we remain surprised at what we perceive. She described an example of shifting from a narrow to a wide focus:

And once when I was lying, weary and bored with myself, on the cliff looking over the Mediterranean, I had said, ‘I want nothing’, and immediately the landscape dropped its picture-postcard garishness and shone with a gleam from the first day of creation, even the dusty weeds by the roadside. Then again, once when ill in bed, so fretting with unfulfilled purposes that I could not at all enjoy the luxury of enforced idleness, I had found myself staring vacantly at a faded cyclamen and had happened to remember to say to myself, ‘I want nothing’. Immediately I was so flooded with the crimson of the petals that I thought I had never before known what colour was.

Milner highlights a paradox about our nature. We may find the most pleasure when and where we least expect it, and this often involves widening our perception and resisting the pull of self-knowledge. In contrast to the Keatsian negative capability, a narrow attention thrusts us into self-improvement projects that may foreclose upon unplanned and unexpected joys. Of course, with well-developed frontal lobes, we are list-making mammals who can’t resist coming up with more things to do. As rational and analytic creatures who have obviously had some success since the Middle Paleolithic, we also enjoy a good puzzle. Still, if we can relax into the kind of wide view described by Milner, we might also discover the joys and pleasures of not knowing.

© 2012 Bruce C. Poulsen, All Rights Reserved