Child Development

The Development of Quantity Assessments

The intriguing case of conservation.

Posted June 10, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Conservation is the ability to understand that a quantity remains the same despite changes in appearance.

- Children under the age of 5 do not master conservation skills and use heuristics to assess quantities.

- Conservation skills develop differently in different contexts and mature until pre-adolescence.

- Conservation skills can be trained and they are associated with quality of decision-making.

During a particular stage of childhood, children possess the ability to engage in complex conversations but struggle to grasp concepts that seem obvious to adults. As I delved into the study of decision-making in children, I encountered a puzzling phenomenon that perplexes grown-ups.

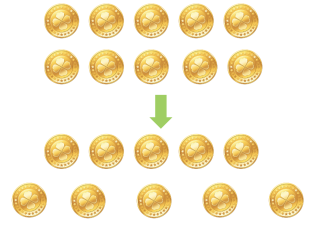

Imagine presenting a four-year-old child with two rows of objects that are identical in length and contain the same number of objects. After ensuring that the child understands the rows contain an equal number of objects, the rows are rearranged in a way that makes one appear longer. Now, here's the intriguing part: when asked whether both rows still contain the same number of objects, the majority of children between the ages of 4 and 5 respond that one row has more objects.

The example outlined above is one of the classic tasks used to assess conservation, termed the "number task." By observing whether a child realizes that the number of objects did not change, researchers can determine if the child has acquired the concept of conservation of number.

Another well-known task is the "liquid task," where two identical glasses are presented to the child. One of the glasses is filled halfway with water, and the child is asked to indicate when both glasses have an equal amount of liquid. The experimenter then transfers the contents of the second glass into a taller and narrower glass, creating the illusion of a different quantity. The child's response to whether the amount of water has changed reveals their understanding of conservation.

Piaget's experiments demonstrated that the development of conservation is a complex process that varies across different contexts. Typically, children between the ages of 4 and 5 struggle with the number conservation task, but by ages 6 to 8, most children have acquired the ability. Conservation of weight is typically mastered around the age of 9, while conservation of liquid tends to be fully understood by age 11.

A common explanation for children's inability to conserve is their focus on salient dimensions and cognitive biases. For example, younger children often concentrate solely on the length of the rows in the number task, erroneously believing that the longer row contains more objects. This bias, known as the "length-equals-number" heuristic, shifts as older children realize the importance of attending to the number of objects.

Researchers have discovered that manipulations can improve children's performance in conservation tasks. For instance, training tasks have proven successful in teaching non-conserving children to correctly complete conservation tasks. Incentives are also capable of shifting behavior.

A few years ago, our laboratory conducted a study aimed at evaluating basic strategic behavior in preschool children. In addition, we assessed their performance in a number task, where we replaced items with toys and informed the children that they could take home the row they selected. In our task, one row had always more items.

To begin, we arranged the objects in a manner where the row with the lesser number of objects was shorter. Subsequently, we rearranged the objects in front of the child, causing the row with the smaller number of objects to appear longer.

Consistent with previous research, we discovered that offering incentives in the number task enhanced the children's performance. Furthermore, we observed that these incentives motivated the children to concentrate on the correct aspect of the problem and engage in counting. This shift in strategy resulted in more accurate responses.

However, the most significant finding was the association between performance in number conservation and strategic play. Children who demonstrated better number conservation skills exhibited superior planning abilities in games and a greater capacity to anticipate their opponents' moves.

Neuroimaging studies have provided insights into the underlying brain mechanisms involved in conservation tasks. Successful performance requires the engagement of structures that inhibit erroneous strategies and enable numerical manipulation. These structures develop gradually, highlighting the importance of motivation in activating attentional processes that are still maturing. These structures are also involved in decision-making which explains the close relationship we found between strategic thinking and conservation.

The intriguing case of conservation sheds light on the gradual development of cognitive skills in children. The tasks have unraveled the complexities of conservation, highlighting the role of salient dimensions and cognitive biases in children's understanding. By leveraging manipulations and incentives, researchers have discovered methods to enhance children's conservation skills. Moreover, the neurological underpinnings of conservation tasks provide further insights into the cognitive processes involved.

Ultimately, cultivating conservation skills in children has far-reaching benefits, empowering them with enhanced mathematical abilities, decision-making proficiency, and strategic thinking.

References

Brocas, I., & Carrillo, J. D. (2018). The determinants of strategic thinking in preschool children. Plos one, 13(5), e0195456.