Attention

Have You Fallen Prey to the "Spotlight Effect?"

You are probably the only one who realizes you're having a bad hair day.

Posted November 21, 2013

Part of the human experience seems to be finding ourselves in highly embarrassing situations. At some time most of us have tripped on the stairs in a crowded area, spilled our drink on a stranger, put our foot in our mouth during an important conversation, or simply had to face the world on a really bad hair day. When I find myself in one of these situations, such as the last time I tripped over my own feet in the middle of campus (a bi-monthly event, at least), I instantly blush and put my head down, hoping to avoid the pity and humor that I’m sure is on the faces of all those who witnessed my moment of embarrassment. But, according to social psychology research, I shouldn’t be so quick to blush and look away. It turns out that the number of people who noticed my mishap are likely to be much fewer than I’d imagined, as we tend to overestimate how much our actions and appearance are noticed by others, something social psychologists call the “spotlight effect."

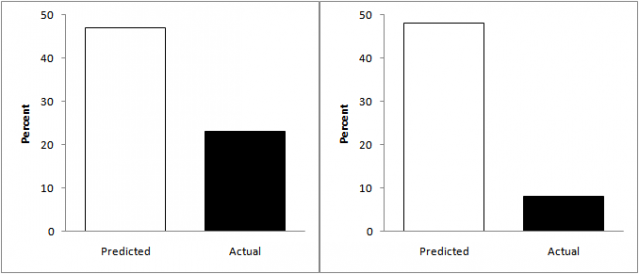

One set of studies by Thomas Gilovich and colleagues (2000) gave the spotlight effect its name and put it to the test. In their first two studies, they had participants put on a shirt with a big picture of someone’s face on it and then walk briefly into a room filled with students sitting at a table facing the door. After the each participant left the room, he or she was asked to estimate how many people in the room would be able to remember who was on their t-shirt, while the observers in the room were asked if they could remember who had been on the shirt. This was all done under the guise of it being a “study on memory.” What did they find? As shown below, in the first study participants drastically overestimated how many people would remember that Barry Manilow (a face they were embarrassed to wear) had been prominently featured on their shirt. Even when their t-shirt had a face that wasn’t embarrassing*, they still overestimated how many people would remember who was on their shirt, suggesting that its not just those moments when we’ve tripped on the stairs that trigger the spotlight effect.

They followed up this first set of studies with a third study where they tested whether the spotlight effect extends not just to people’s appearances, but also their actions. They had people get into groups to talk about “the problems of the inner cities” for 30 minutes. At the end of the conversation each person estimated how the whole group would view their performance and the performance of each of the other members of the group. As with the previous studies, whether the participants were thinking about what they’d done right or were asked to recall their more embarrassing moments during the conversation, they tended to overestimate how much attention had been paid to them.

So why do we think everyone’s paying attention to us? Gilovich and colleagues suggest its because we are so focused on ourselves. We are acutely aware of our own appearance and actions, and we have trouble realizing other people might not be as focused on us. This is an example of a phenomenon called “anchoring and adjustment.” We are anchored by our own experiences and we have trouble adjusting far enough away from them to accurately estimate how much attention other people are paying us. They found evidence for this when they ran the Barry Manilow t-shirt study again, but had half the participants wait for 15 minutes in a nearby room before they completed their estimations. By delaying the estimation process, the experimenters gave the participants time to get used to wearing their shirts. Once the participants were comfortable in their shirts, they were no longer as aware of Manilow’s face, and along with this, they no longer assumed everyone else was as well. These findings suggest that they had indeed been using their own experience to estimate what everyone else was thinking. I know this rings true for my own experiences—the day after an embarrassing haircut I am sure the whole world is pointing and laughing, but four days in when I’ve gotten used to the face in the mirror, I think everyone else has too, even if they are seeing if for the first time.

The bottom line: No need to blush and run the next time you embarrass yourself since you are probably the only person who was really paying attention to your mishap. But you also have to give people a break when they don’t notice your new shirt or compliment you on that really smart comment you made during a meeting. They aren’t paying as close of attention to your appearance and actions as you are because they are too busy paying attention to themselves.

*who did students of the 90’s see as not embarrassing? Bob Marley, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jerry Seinfeld

What do you think of these studies? Do you fall prey to the spotlight effect? Do you pay much attention when people around you do embarrassing things?