Synesthesia

Synesthesia is a neurological condition in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway (for example, hearing) leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway (such as vision). Simply put, when one sense is activated, another unrelated sense is activated at the same time. This may, for instance, take the form of hearing music and simultaneously sensing the sound as swirls or patterns of color.

Sight, smell, taste, touch, sound… and synesthesia? Though we’re no closer to discovering a true sixth sense, research suggests that synesthesia may confer some sensory enhancements. Some scientists posit, for example, that synesthetes are better at distinguishing between smells as well as between colors.

Synesthesia can enhance cognitive abilities such as creativity and memory, as it’s easier to make connections between concepts. Renowned creative minds such as Vincent Van Gogh and Vladimir Nabokov claimed to have synesthesia.

Synesthesia can be associative, so senses are connected and associated in a person’s mind, or projective, when the images and colors are projected into reality.

A person who reports a lifelong history of synesthesia is known as a “synesthete.” They often (though not always) consider synesthesia to be a gift, allowing them to see the world through an integration of multiple senses that is truly unique. Consistency is one sign of a synesthete—for instance, repeatedly associating the same color with a sight or sound.

It is estimated that approximately 3 to 5 percent of the population has some form of synesthesia and that women are more likely to become synesthetes than men.

Synesthesia often appears during early childhood. Research has shown signs of a genetic component; there is some debate over whether everyone is born with some degree of synesthesia, or if it’s a special perception of the world that only some individuals share.

In rare cases, synesthesia can develop later in life, either temporarily from the use of psychedelic drugs, meditation, and sensory deprivation, or permanently, from head trauma, strokes, or brain tumors.

Research shows that synesthetes tend to have more vivid mental imagery than non-synesthetes. Some say this is associated with greater connectivity in the brain. Synesthetes also demonstrate more creative thinking, discovering that metaphors come easily.

No, synesthesia is not an illness or mental disorder. Rather, it’s a fresh way of experiencing the world through a mixing of the senses that is unique to the individual.

Yes, there does seem to be a genetic component to synesthesia, which can be passed down from parent to child.

The earliest mentions of synesthesia were recorded by 19th-century scientist Francis Galton, although research would not begin in earnest until the late 20th century.

Since synesthesia can involve any combination of the senses, there may be as many as 60 to 80 subtypes. However, not all types of synesthesia have been documented or studied, and the cause remains unclear. Some synesthetes perceive texture in response to sight, hear sounds in response to smells, or associate shapes with flavors. Media like books, films, and TV shows often take advantage of the multimodal mental imagery associated with synesthesia (which explains the popularity of cooking and baking shows).

While nearly any sensory combination is possible in synesthesia, here are some of the most well-known ways it manifests:

- Auditory-tactile synesthesia occurs when a sound prompts a specific bodily sensation (such as tingling on the back of one’s neck).

- Chromesthesia occurs when certain sounds (like a car honking) can trigger someone to see colors.

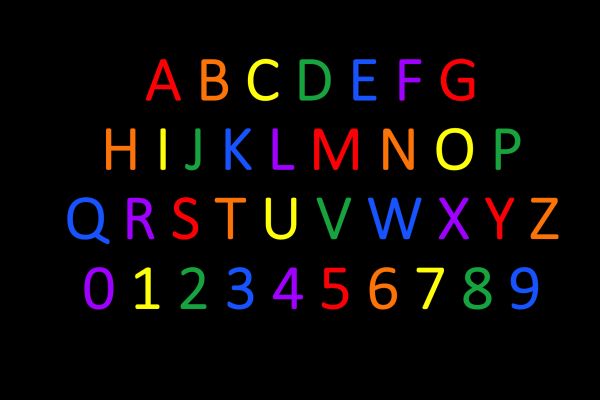

- Grapheme-color synesthesia occurs when letters and numbers are associated with specific colors.

- Lexical-gustatory synesthesia occurs when hearing certain words triggers distinct tastes.

- Mirror-touch synesthesia has been described as a kind of supercharged empathy: A person feels as though they’re being touched if they witness it happening to someone else. It can be benign—such as an observed advantage in recognizing facial expressions—or burdensome, as in the case of a neurologist who felt intense pressure in his chest when he saw a patient receiving CPR.

- Number form occurs when a mental map of numbers involuntarily appears whenever someone thinks of numbers.

- Ordinal linguistic personification is a kind of synesthesia where ordered sequences (e.g., the days of the week) are associated with personalities or genders.

- Spatial sequence synesthesia involves seeing numbers or numerical sequences as points in space (e.g., close or far away).

Many synesthetes have more than one type of synesthesia. It is estimated that 4 percent of humans have some form of synesthesia, though the percentage who have multiples types is much smaller.

The most commonly seen example of synesthesia is grapheme-color synesthesia, in which individual letters and numbers are associated with specific colors and sometimes colorful patterns. Chromesthesia, the association of sounds to colors, is also fairly widespread.

Synesthetes can experience some strange and compelling associations. For instance, they may be able to taste letters (lexical-gustatory synesthesia) or have a strong spatial experience when thinking about time units (spatial time units/sequence-space synesthesia). Swimming-style synesthesia, or seeing colors when watching or thinking about a specific swimming stroke, is also unusual.

There’s no clinical diagnosis for synesthesia, but it’s possible to take tests such as “The Synesthesia Battery” that gauge the extent to which one makes associations between senses. To truly have synesthesia, the associations have to be consistent. They should happen every single time one invokes one of the two senses, over a span of time, and be memorable experiences: Letters are associated with the same very specific shade of a color every time they’re read, and sounds always evoke the matching texture, even months later.

Because synesthesia is not widely studied, not all researchers agree on these standards. Some scientists speculate that everyone is born with a degree of synesthesia because the infant's brain is hyperconnected, and these connections are pruned as it develops. In fact, synesthesia can decrease over time.

Be aware of those times when you have associations that involve two or more of your senses. (Perhaps you see the letter “A” as pink, or maybe the smell of gasoline looks like a brown fog.) These are some examples of how synesthesia might manifest, which involve cross-talking between your senses.

There are many different types of synesthesia tests, including both visual and auditory. Many of them are designed in a test-retest format. Consistency across multiple testing sessions helps to rule out the possibility that someone is making up their associations versus being a true synesthete.

For certain types of synesthesia, you can take the Synesthesia Battery, an online test, to help confirm.

Yes, some synesthesia experiences are more mild than others. For example, associated synesthesia is generally less intense and disruptive than having different sensory combinations projected into reality.