Psychology

The Psychology of Artistic Expression: Verbal vs. Visual

When writers paint, how do words and visuals intersect and inspire each other?

Posted September 17, 2020

The intersection between visual and written forms of artistic expression is a fascinating space to explore. It is particularly interesting when writers become painters or vice versa.

Painting and visual art have an immediacy of impact on the viewer and are in some ways more brazen and controlling of the viewer’s imagination than writing, which relies heavily on a collaboration with the reader’s internal musings. Not to say that writing cannot be striking and driven in its own right; an author’s point of view is never in question, just the mental filter through which it comes alive in the reader, so writing feels slightly more oblique and indirect than visual art.

Both writing and painting can leave the viewer/reader befuddled and feeling left outside instead of embraced, especially in this era of abstraction and conceptual art. But when the viewer/reader tries to look at both modalities proffered by one person, the author’s intentions might come into better focus.

For the writer who paints, their visual expression can be an intriguing foray into what they are trying to achieve with their words. It isn’t as surprising perhaps to see poets who paint, given that poetry relies more on abstraction and aesthetic mood.

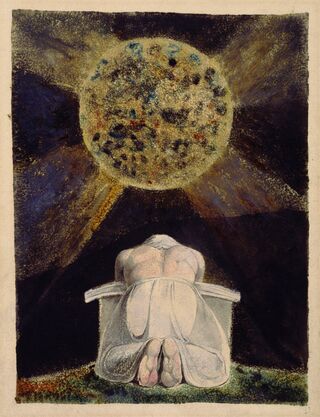

The British Romantic artist, William Blake, made the most of both worlds with his illustrated mystical poetry. His images are blazing, grandiose, hyper-spiritual, with sharp contrasts of dark and light and a mixture of religious and fantasy figures. His poems are also musical, expressive, and can also reach a similar fever pitch of feeling as with "A War Song to Englishmen":

"Prepare, prepare the iron helm of war, Bring forth the lots, cast in the spacious orb; Th’ Angel of Fate turns them with mighty hands, And casts them out upon the darken’d earth! Prepare, prepare!"

He was one of the few artists who maximized his commitment to both genres, and in doing so achieved a precursor of cinematic dynamism in his work, by having language dance alongside vibrant illustrations. He understood the power of synesthesia, of multiple senses being engaged simultaneously for different reverberations of meaning and effect. Fiery words allied with fiery visions pushed Romantic art to another level.

However, most famous writers who paint have kept it as a quiet side pursuit or switched gears from one craft to another. At age 20, Sylvia Plath almost decided upon an art career but went into writing instead. A set of her early drawings was released by her daughter and exhibited in London in 2011. The drawings are remarkably benign in subject matter, cutesy even, like a pair of heels, farm animals, or a citronnade stand in the park. Yet I see something of her future self in the precision of the lines, the crisp characterization of figures with an economy of purpose.

She continued to paint throughout her life (Ted Hughes reportedly encouraged her because the activity seemed to calm her). Some of her later art shows a jazziness, like Mad Men fashion ads meet Picasso, with bright, chaotic colors and geometric, neo-cubist lines. They are a bit unsettling, because of their fragmented, kaleidoscopic, acid nature, but also reassuring in their calculated freedom, their cataloguing different patterns, colors into an expressionist crazy quilt. She still seemed to be at play, as opposed to her poetry, where her dark muse was in full wrathful force.

Mark Strand, a poet who also initially began with a painting career (getting a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Yale), had returned to his first love of late. In a September 2013 New Yorker post by Rachel Arons, he is interviewed about an exhibit of new collages on display at a Chelsea gallery. They are described as “playful” as well; again a freedom or escape from the pressures of “trying to make verbal sense” in writing.

The collages are highly abstract, filmy patches of colored paper crudely pasted against each other, and indeed, somewhat childlike in execution. The colors vary from those of bright tropical fruits to placid pastels to muted grays; the stone-like roughness of the shapes let the colors converse with each other on their own terms. The mood is all.

He says visual art for him is an active “escape from making meaning." This return to primal expression is fascinating, given the poised precision of his poetry. His writing has in common the emphasis on mood, the careful placement of seemingly plain words in an artful alliance, not unlike the movements of an interior designer, where the overall composition and harmony matter as much if not more than the individual pieces on display. For example, this short 2002 poem, “The Coming of Light:

“Even this late it happens: the coming of love, the coming of light. You wake and the candles are lit as if by themselves, Stars gather, dreams pour into your pillows, Sending up warm bouquets of air. Even this late the bones of the body shine And tomorrow’s dust flares into breath.”

But with Strand’s collages, the mood is more bluntly achieved, through color and shape alone, on an innocent, pre-verbal level. Perhaps at this late stage of life, he feels that the essence is enough. The striving for linguistic precision obfuscates his pure love of expression.

Annie Dillard, another master “word painter” who mainly worked in prose (albeit beautifully styled), has also taken up painting, after declaring herself retired from writing in 2007, and exhibited and sold some of her works in small galleries. (The proceeds go to charity.) Her works are reportedly all small-scale (less than 16-inch canvases) and mainly portraits and landscapes (given her obsession with nature), with simple subjects like roads, flowers, fences, hillsides.

Like her language, there is a charismatic poise to her choice of colors and figures, but also a certain lightness and softness that isn’t as evident in her diamond-hard prose. Take this excerpt from Pilgrim at Tinker Creek:

“The air bites my nose like pepper…The rutted clay is frozen tonight in shards; its scarps loom in the slanting light like pressure ridges in ice under aurora. The light from the moon is awesome…not the luster of noonday it gives, but the luster of elf-light, utterly lambent and utterly dreamed.”

Her obsession with gradations of light and imagery are evident in her subject matter and gorgeously precise. With her paintings, there is the same admiration of light and vision and beauty, but, as with Plath, now there is a certain freedom that comes from attempting a new line of expression unburdened by expectation—a feeling of innocent pleasure and peace. It is freedom from the perfectionist genius that sometimes drives writing, especially prose, because on some level, language is constrained by rules of grammar, vocabulary, coherence–rules that can arguably bend a lot more with painting and still produce its intended effect (masters of realism notwithstanding).

I encourage readers to look up these curious cross-genre novelties, for what new angles and insights they shine upon the writer’s artistic goals and method of expression. They can stimulate new admiration for what both modalities can accomplish, and how they can inform each other.

Perhaps as writers, we also need to remind ourselves of that mode of innocent curiosity and exploration that can be discovered when switching “teams” into the nonverbal, visual art zone. We can discover that evocation of our childhood sensibilities, when curiosity for its own sake and playful creation captured something pure and truthful in ourselves and our lives, and that was all we needed to succeed in our mission as artists. Perhaps we ought to put less pressure on ourselves and let our creativity flow without the burden of perfection. It may still be beautiful enough.

Copyright Jean Kim. This piece was also published in Niche Literary Magazine's blog, which is now defunct.