Fear

Recognizing Our Common Humanity

Can finding common ground with others help us find peace?

Posted May 15, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Try to find common ground with people—especially those you fear or are angry with or different from you.

- Try thinking of “us” with others is to see our common humanity and recognize that we all want.

- When you notice that you are “them-ing” others again, stop fueling this process.

- Play with the sense of being an “us” to others.

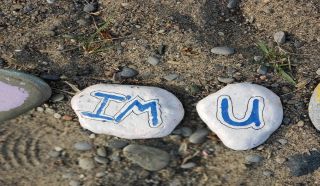

Finding common ground with every person—especially those you fear, are angry with, or who are simply very different from you—is a practice that is, these days, more important than ever.

For most of the past 300,000 years, our human ancestors lived in small bands of about 50 people in which they survived by being good at caring about and cooperating with people inside the band—with “us”—while also being good at fearing and aggressing upon people outside their band: “them.” And for 2 million years before that, our hominid ancestors lived and evolved under similar pressures.

That’s a long, long time. And during the last 10,000 years, as agriculture produced food surpluses that enabled larger groups, this same tribalistic pattern has repeated at bigger scales. While there are heartening examples of people extending themselves to strangers, most of us are vulnerable to the ancient drumbeats of grievance and vengeance—now amplified to thunder by modern technologies like social media.

And it’s not just in our politics. You can see the “them-ing” of others as you walk down a street in the rapid sorting of people into like-me and not-like-me. You can see it in office politics and family discord. The in-group and out-group, the casual dismissals, the turning away in anger, the easy disdain. You can see your mind moving so quickly to reduce another person to a 2-dimensional figure as you invest in your own position and identity—even when that person is your beloved mate.

You also know what it’s like to feel “themed” yourself. To be ignored, discounted, used, attacked, or tossed aside. Not good at all.

To “us” others is to see our common humanity—to recognize that we all want pleasure and fear pain, that we all are frail, that we all suffer and die, and that each of us will be separated one way or another from everything we love someday. As you see this fact and the deep, deep ways we’re like each other, a wary tension in the body eases. Then you see others more clearly and can be more effective with them, even those you oppose fiercely. And when you don’t feel needlessly threatened, you’re less likely to be needlessly threatening.

The Practice

Take a little time to know what it feels like to be “me,” to be part of an “us,” and to see those who are “them.” Then be mindful of when your mind is “us-ing” or “them-ing” other people.

They can be quite subtle yet consequential—those moments when we look away, lose empathy, stereotype, discriminate, cast out, or punish. When you notice that you, like me, are “them-ing” others again, try to stop fueling this process; step back, climb back down the ladder of anger, and see the bigger picture, the larger whole that contains you and the other person in a single “us.” Help it sink in that you can still stand up for your rights and protect those you care about without dehumanizing others into “them.”

As you move through your day, see similarities between yourself and others. For example, when you see a stranger walking down the street, take 20 seconds to really look at them and get a sense of “Wow, they’re like me. Their back hurts like mine, they love their kids as I do, and they, too, have felt joy and sorrow.”

Try this in particular, with people who seem very different from you and with people who belong to groups you may mistrust or fear or dislike. Notice what this practice feels like for you—probably heart-opening, calming, and actually strengthening.

Also, imagine a kind of circle that includes you and others you like, and then gradually widen that circle in ways that feel genuine to you. This could mean gradually including people you know but feel neutral about, including people you don’t know but are like you in some ways, then including people who are unlike you, and eventually including people you don’t like, perhaps who have harmed you or others, knowing you don’t have to approve of them to recognize our common humanity. Take your time with this, drawing on compassion for yourself and others and expanding the circle only as it feels true and right for you. Be aware of a softening in yourself as you do this, a releasing of defensiveness and righteousness, a widening of your perspective. Rest in how this feels, and enjoy it.

You can also play with the sense of being an “us” to others. Start with those who naturally include you, and notice what this feels like. Then you could try this with people who may not initially see their common ground with you—and as appropriate, you could do little natural things to establish similarities and connections, like finding out if you both have children or that you both have a sarcastic sense of humor or simply that you do not wish each other harm.

It’s often in these simple ways that bridges build among us, circles widen, and we come to live together in peace.