Addiction

Who Is The Real Father of Sex Addiction?

A fascinating new book now reveals a dark history for sex addiction

Posted October 2, 2015

The history of the concept of sex addiction is a complex, somewhat contentious one. As a writer and critic of the sex addiction industry, I’ve often cited the concept back to the initial writings of Patrick Carnes, and his first 1983 work. Some researchers and proponents of the concept have gone much further back, even to a signer of the Declaration of Independence, physician Benjamin Rush.

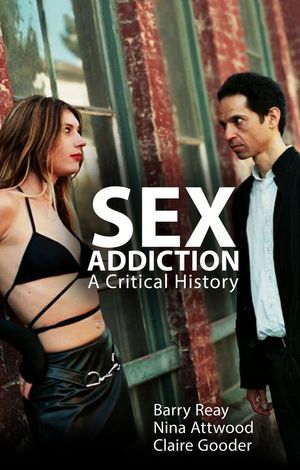

Now, three New Zealand historians have contributed a wealth of astounding, rich and often surprising information to the issue, with the first book chronicling the history of this influential concept. Sex Addiction, A Critical History, was published in 2015, and represents a remarkable detailing of the troubling, often hidden, history of this concept.

“Sexual addiction is a newly coined term for a disorder as fictitious as thirst addiction, hunger addiction or reading addiction. Sexual addictionology does not address the specificity of addiction. Instead it decrees that the only nonaddictive form of sexual expression is lifelong heterosexual fidelity and commitment in monogamous marriage. Everything else is the gateway of sin through which exits the broad road to sexual depravity, degeneracy and addiction. Within addictionology, the wheel of degeneracy has made a full turn.” John Money, 1989, p. 6 in Reay, et al.

Reading the book is surprising, even for scholars of sex addiction. The surprises start on the first pages of this book, with the revealing and even titillating origins of the term sex addiction, in 1950’s pulp erotica and pornographic novels, where sex addict was used as a salacious tem of erotic excitement. One book was called "Love Addict" with the teaser, "He couldn't klck the habit," and a cover showing a uniformed man spanking a buxom woman. It's ironic, that sex and love addiction was first used to sell porn, and now is used to condemn it.

But why do New Zealanders care about sex addiction? It’s mostly an American concept, reflecting, in many ways, Western conflicted attitudes towards sex. The book’s authors explained to me that sex addiction has become a global phenomenon, with worldwide impact:

“As academics, we chose to work on sex addiction interested in the global history of sex. I have published on the history of sex in both England and the US (including a book on hustlers in New York). Nina published a book on 19th-century English prostitution. Claire has researched and published on the history of New Zealand sex education but in order to do that she read widely in an international literature. More specifically we were all teaching a first year university course on the history of sex – with no New Zealand content – which included reference to sex addiction. I had been teaching that course since the late 1990s and used Janice Irvine’s 1995 article “Reinventing Perversion,” an early critique of the rise of the concept. Eventually, we became curious about the history of sex addiction after Irvine’s summary.

In this internet age, cultural/medical phenomena are not limited to one country, and the idea of sex addiction has “popped up” in New Zealand – but perhaps not with the intensity experienced by you in the US.”

It’s often argued that the debate over sex addiction is merely a semantic debate, over what to name it. There are dozens of terms employed over the years, from nymphomania to hypersexual disorder or erotomania. But Reay and his colleagues didn’t get bogged down in this morass of semantic confusion, and even suggested to me that they thought this argument over a name was a distraction, away from much more important issues of substance:

“we thought that the discussion about what to call it, much like the obsession with measuring it, deflected thinking away from whether there was actually anything of substance to name or measure in the first place.”

As historians, this work brings an outside, nonclinical eye to the question of sex addiction, based upon what has actually been written, created and said about sex addiction. As a result, this book doesn’t delve as much into a clinical debate over whether sex addiction is or isn’t a disorder. Instead, the work explores the rich cultural and social dynamics that brought sex addiction into being. Though the authors went into their exploration as neutral outsiders to the concept, their investigation led them to take a critical stance against the concept of sex addiction:

“We were interested in sex addiction as a construct rather than a given truth. We knew that it had a history, a short history, and we were interested in exploring that. I think that I said in another interview that while we were skeptical about the concept, having read Irvine (who, by the way, is a sociologist), we did expect to find more justification for the concept. We thought that because sex addiction had been so successful as an explanation for (vaguely defined) out-of-control sexual behavior there would be more basis to it. But the more research we did, the more and more critical we became. We said in our introduction to the book that Trysh Travis’s history of Alcoholics Anonymous was different to our project in that she refused to take a stance, remained neutral. We found that impossible. Even when, in Chapter 3, “Addictionology 101,” our intention was to merely set out the claims/beliefs of addictionology, we found it difficult not to comment critically (we had to continually edit out such comments in that chapter). Of course no histories are neutral. Opinion intrudes in all sorts of ways. But I have never written a book that is so unrelentingly critical: it certainly lives up to its subtitle, “A Critical History.””

Despite the fact that sex addiction has always had powerful critics and challenges, many of them cited in Sex Addiction A Critical History, the concept has enjoyed decades of popular success and growth, largely outside the traditional mental health system. “The short answer is the supposed disease has been defined, built and reinforced through an industry of therapists and therapy-speak; in workbooks for addicts and partners, and textbooks for clinicians; through websites, and social networking services. We have become culturally habituated to the concept; our book discusses the roles of the press, internet, TV, film, literature, and even library classification in this process, and the manner in which the supposed malady has become the unthinking default explanation for any kind of promiscuous or obsessive sexual interaction. And it is important that all of this has occurred in a culture obsessed with psychiatric disorder and addiction, what has been termed therapy culture. In fact it would have been curious if sex had remained immune to inclusion in that myriad of disorders and addictions that we are all supposed to be suffering.”

One of the most startling aspects of the history of sex addiction, is who they name as the “father” of sex addiction. For years, most of us hang this laurel on the shoulders of Dr. Patrick Carnes. Instead, Reay, et al name Dr. Lawrence Hatterer, Cornell psychiatrist as the true father of the modern sex addiction concept. Though rarely cited by modern addictionologists, Reay and his coauthors found powerful writings by Hatterer from the 1960’s and 70’s, where he blamed a sexually addictive process for sexual excesses. Powerfully, they detail Hatterer’s disturbing history of treating homosexuality as an illness, and the way he treated homosexuality “like an alcoholic,” with “addictive hypersexualized living” and “addictive sexual pattern” in his writings, including the book Changing Homosexuality in the Male. so, from its inception, the concept of sex addiction has ben applied to treatment of homosexuality as an illness. It's worth noting that Hatterer wrote about homosexuality as an addiction prior to the APA removing homosexuality from the DSM. But, he continued his use of the concept that sex was addictive into the 1980's.

Given the fact that formal sex addiction groups have publicly rejected the use of addiction treatment to “cure” homosexuality, it is perhaps understandable that Hatterer represents a piece of their history which sex addiction therapists would prefer to forget. Sadly, one doesn't have to look far to find that many today are still following in the true Father of Sex Addiction's footsteps. Remember that those who ignore their own history may be condemned to repeat it.