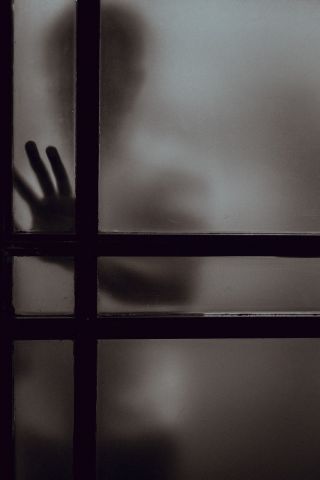

Stalking

What’s Love Got to Do With It? Ex-Partner Stalking

The purpose of pathological ex-paramour pursuit.

Posted July 3, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Ex-partner stalkers can be motivated by reconciliation or retaliation.

- A stalker's motivation determines the pathway of unwanted pursuit behavior.

- Victims need to be firm and consistent in resisting a stalker's overtures.

Rose petals on the front porch, a favorite brand of chocolate delivered to work—such expressions of romantic sentiment often accompany Hollywood-inspired stereotypes of behavioral patterns of ex-intimates desiring to rekindle the relationship. Real stalking victims are more likely to fear returning home to a dead cat or ominous message taped to their refrigerator, demonstrating a woman’s ex-paramour-turned-pursuer has been in her home. Understanding the real motivation behind romantic misperception can help protect victims and manage stalkers. Research explains.

No Love Lost

I have prosecuted stalkers for decades, most of whose attention evolved from focus to fixation after an unwanted breakup. Some jilted lovers mourn “love lost” regardless of the often very short relational duration, including after one-night stands. Others experience unrequited love, having never moved beyond the acquaintance stage before rejection triggers obsession. Yet because stalking creates fear, often by design, and can be dangerous, understanding the true dynamics is of utmost importance.

Revenge Over Rejection

Christina M. Dardis and Christine A. Gidycz (2019) examined the difference in unwanted pursuit behavior among stalkers motivated by reconciliation or retaliation.[i] They begin by discussing several theories that have been advanced to predict the extent of unwanted pursuit behavior (UPB) following romantic relationships, including relational goal pursuit, coercive control theory, and attachment theory. They assessed a proposed integrated model (Davis, Swan, and Gambone, 2012) of both cyber and in-person UPB toward former partners among an undergraduate sample.

Dardis and Gidycz found support for the integrated model through two primary pathways: the first based on relational goal pursuit theory, motivated by a desire for reconciliation and associated with minor UPBs, and the second based on coercive control theory focusing on retaliation motives, which was associated to a greater extent with severe cyber and in-person UPBs. How does this happen? Dardis and Gidycz found self-control difficulties and possessiveness impacted UPB perpetration mainly along the coercive control pathway, and anxious attachment impacted the pathway to reconciliation. There were few gender differences displayed among the models, although interpersonal violence by male perpetrators was more significantly linked with more severe UPBs than women’s perpetration of interpersonal violence.

Consequently, the implications of recognizing the motivation behind the obsession is of considerable importance to the safety of the victim and his or her family. And so is adopting an accurate perception of the pathology behind the pursuit.

Recognizing When the Bloom Is Off the Rose

Victims of ex-partner stalkers who once bought them roses need to ensure they are not viewing a perpetrator’s conduct through rose-colored glasses post-dissolution. When they accurately observe and recognize a stalker’s motivation, they are in a better position to take steps to protect themselves. In all stalking cases, a firm “no” followed by a consistent pattern of nonresponse to a stalker’s overtures is the best way to quash unrealistic goals of reconciliation, and involving law enforcement is often the best option in seeking victim protection and perpetrator redirection.

References

[i] Dardis, Christina M., and Christine A. Gidycz. “Reconciliation or Retaliation? An Integrative Model of Postrelationship in-Person and Cyber Unwanted Pursuit Perpetration among Undergraduate Men and Women.” Psychology of Violence 9, no. 3 (May 2019): 328–39. doi:10.1037/vio0000102.