Freudian Psychology

Hidden Mentors: Sophie Freud and Me

Personal Perspective: She didn't realize it, but she changed my life.

Posted July 18, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Sophie Freud was an inspiration to many, probably without realizing it.

- She was an important mentor in my life, even though I understood her influence only belatedly.

- You might never know that others consider you a mentor.

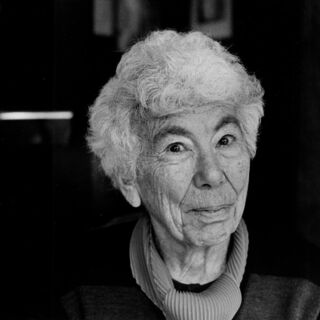

Sometimes people can influence you, and you don’t even realize it’s happened until much later in your professional trajectory. Even though I’ve been thinking and writing about mentors a lot lately, my reaction to the recent death of my former professor, Sophie Freud, took me a little by surprise. I hadn’t realized until now what a great mentor she had been in my life—in fact, I’d never thought of her as one. And then she died, and I realized—albeit belatedly—how much she did to inspire me.

Sophie Freud was influential to so many people, both publicly and academically.

Though she was Sigmund Freud’s granddaughter, Sophie didn’t exactly follow in her famous grandfather’s footsteps; she spent most of her career instead challenging and eventually repudiating his theories of psychoanalysis. “I’m very skeptical about much of psychoanalysis,” she told the Boston Globe in 2002. “I think it’s such a narcissistic indulgence that I cannot believe in it.”

I liked the way The New York Times described her reaction to her grandfather in its obituary:

While he often challenged the Victorian era’s patriarchal view of female sexuality, she wrote, “he mirrored in his theories the belief that women were secondary and were not the norm.” As for his conclusion that “women are forever falling in love with their male therapists,” she said, he sanitized such attachments as transference.

“He said it doesn’t matter, women get over it afterward,” Professor Freud said, “but I disagree. Women then go to another therapist to get over that one.”

Sophie Freud (who, by the way, never went to therapy herself) instead became interested in children’s welfare and in introducing feminism into the field of social work. After earning her doctorate at Brandeis, she became head of the human behavior program at Simmons College School of Social Work (now Simmons University) and subsequently spent her career teaching, leading, inspiring… even establishing her identity as a true “character” (she arrived at school on a bright red motorbike wearing something akin to a space suit until well into her 70s!).

Sophie was a rigid academic and had a daunting presence. She was also a woman who influenced me more than I’d realized when it was happening. It wasn’t until I read her obituary that I realized how important she’d been in shaping my career.

Recognizing a hidden mentor:

I arrived “early” at the graduate program at Simmons School of Social Work, right out of my undergraduate work at age 21. That was widely considered to be quite young for the work; most social-work students put in some time in the real world first. Professor Freud conceded, drily, that other students were indeed “usually more sophisticated.” That certainly put me in my place! I don’t know whether she said it to validate my experiences or to mobilize me to succeed, though I suspect the former. Little did I know how much her remark would motivate me—mostly in an effort to prove her wrong!

Over the year I spent as her student, I learned to love the nuances of being human and the experiences of internal and interpersonal connections. Not only did she curate a list of favorite articles—the gift of a lifetime from a master—but her fascination with experiences and dynamics taught me to look at others and enjoy them through a similar lens.

She taught what was at the time heretical thinking: that unconscious forces weren’t the only factor to pay attention to, that social and family systems were just as important. I’ve embraced that thinking wholly in my own practice.

I learned that my enthusiasm when sitting with people made me as influential to them as she was to me, albeit in a different way. I was impressed with her passion for psychological nuance. I used to sit in her classes in awe when she discussed the weekly readings or what made people tick. Her fascination with human behavior was powerful—and infectious.

From her, I learned that what may be obvious to us as clinicians can translate to our clients as perspective and wisdom.

None of that was to say she was a comfortable person to be around—far from it! Peculiar and eccentric in many ways, she barely smiled, and when she did, it was hard to know how to interpret it: mischievous, for sure, but obligatory or sincere? We never knew.

Now I understand that it was sincere, expressing the joy of sharing her enthusiasm with her students. During group sessions in a simulated therapy group, she’d sit and knit, seeming to pay more attention to her scarves than to us. But she never missed a beat. She was well aware of her role and what we as individuals and a group were creating together. She didn’t have to do the work for us because we did it ourselves through her facilitation.

I often felt I didn’t measure up to her expectations, and this spurred me to try harder, to work more, to find that elusive something she was looking for. Maybe it was in my best interests all along.

In those days, students handwrote essays in blue notebooks; professors were often seen around campus balancing a stack of them. In one of mine, I wrote about coming out. It was still new for me, and I hadn’t become fully comfortable in my self-understanding. I was taking a risk, using a graduate school essay to describe my experience. To my surprise—and gratitude—Professor Freud expressed herself as “moved” by the essay. Her subsequent comments showed she’d put a lot of thought and attention into what I was saying about my life. It enabled me to take even more risks throughout my career trajectory.

Thirty-nine years later—now—I read about her death, and I feel real grief. Sophie Freud was never a friend, but I never really realized what she represented in my life: a vital and valuable mentor. As time passed, I would think about what she said in class, how her fascination with humans had inspired me—but I didn’t do it frequently, and never for very long. Yet she is reflected in every interaction I have with clients and supervisees: I can see her influence as I work with people to interpret their lives and work.

Did she know how important she was to me? Possibly. Probably not. Powerful professors aren’t always aware of the impact they have on others. But I’ll be forever grateful for the impact she had on me. Her indirect connection and serious nature left me intimidated and wondering if I measured up at the time; I now realize that, indeed, I did. If only I had known this sooner, maybe I would have reached out and thanked her.

I suspect I am not alone in this experience.

Sometimes our biggest influencers and sources of inspiration aren’t who we assume them to be. Keep your awareness open to the powerful influencers who are your best teachers, and thank them now, before they, too, pass on.

Thank you, Sophie Freud.