Race and Ethnicity

Is the “Asian Americans” Documentary a Win for Brown Asians?

Though hailed as a landmark, the series still privileges East Asian experiences.

Posted May 14, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

The new PBS documentary series titled “Asian Americans” has received plenty of hype, and many people seem to like it.

Including me. I really like it.

With all honesty, though, I initially approached the documentary with caution because I have been disappointed many times before by things that claim to be about “Asian Americans." As a Filipino American, my community has been historically forgotten.

This is true in the field of psychology as well. For example, a simple search on PsycINFO—the largest database of psychology-related literature—found 8,568 hits for “Chinese American," 4,923 hits for “Japanese American," 3,125 hits for “Korean American," 1,889 hits for “South Asian American," and 919 hits for “Vietnamese American," but only 836 hits for “Filipino American” (as of May 14, 2020) even though Filipinos are the third-largest Asian American ethnic group (20% of the Asian American population).

So I didn’t want to get my hopes up because history has taught me that my people tend to be marginalized and disregarded even within the Asian American umbrella; even by well-meaning folks who do amazing things for the pan-ethnic Asian American community.

I was afraid history was going to repeat itself. Again.

To my surprise, however, the series opened with the story of the Igorot People during the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Not only did the documentary start with this history, but they actually interviewed an Igorot woman to discuss it and shed some light on the experience. That’s some principled filmmaking right there! Plus, the episodes featured several other folks who I know are respected leaders in the Filipino American community. Thus, right from the get-go, I was already beginning to shift from being suspicious and cautious toward having a very positive impression of the series.

So I kept watching, and the feature on Larry Itliong and the manongs further got me. Then they also covered the important role Filipino Americans played in starting ethnic studies! I was beginning to love this series.

And I especially love how one of the main messages of the documentary is to not let the many examples of this country’s oppressive, painful, and traumatic history repeat themselves.

I was this close to hailing it as a win for all Asian Americans!

I quickly caught myself, however, because I am just one person and the scientist in me says that’s too small of a sample. Also, my feelings about it might not be completely objective. Given the relative deprivation that my community has experienced over generations, I was careful not to be simply happy with whatever we get. That is, I didn’t want to be content with getting $10 because we were getting zero before, when what we really deserve is $20.

That’d just be a sad case of internalized oppression.

Even further, the Filipino American community isn’t alone in its historical marginalization within the Asian American umbrella. South Asians and Southeast Asians—other Brown Asians—also tend to be forgotten because of the persistence of the dominant but inaccurate narrative that “Asian” equals East Asian. So I tempered my joy because I didn’t want to celebrate what I felt to be increased Filipino American representation at the expense of further erasing other marginalized Asian Americans.

Therefore, I needed something that can help me better decide if this documentary was a win for Brown Asians or not.

And the data-driven person within me took over. Yup, I nerded out.

Method

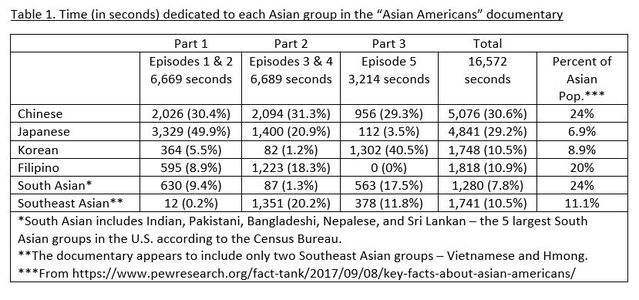

I decided to do a simple analysis of the documentary in order to get some more data that can inform my impression of it. I wanted to know how much time was devoted to different Asian American groups.

So while re-watching the whole series, I kept track of the time—in seconds—that was spent on discussing topics that were explicitly about the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos, South Asians, and Southeast Asians. I also kept track of the time when a Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, South Asian, or Southeast Asian person was speaking or being featured. Times when a speaker of a certain ethnicity is discussing a topic about another ethnicity (e.g., a Chinese American woman talking about her experiences in Vietnam, a feature on a Japanese American soldier fighting in the Philippines during World War II, etc.) counted for both Asian groups.

I did not keep track of the times when the narrators (one Korean American and one Japanese/Filipina American) were speaking about Asian Americans in general, the times when other speakers were talking about Asian Americans in general, and of the times when images of various Asian Americans were being quickly flashed.

Results

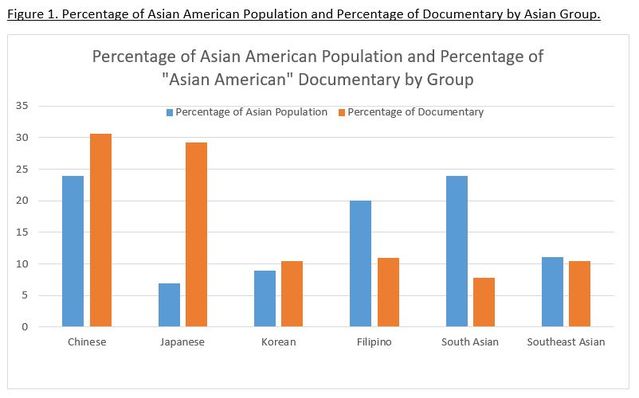

As can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 1, the documentary spent a disproportionately large amount of time featuring East Asians (Chinese, Japanese, Koreans) or discussing topics about East Asians. Approximately 70.3% of the documentary involved East Asians when they collectively compose only around 39.8% of the Asian American population. The disparity is largest with Japanese, as approximately 29.2% of the entire documentary involved Japanese but they compose only 6.9% of the Asian American population.

In contrast, the documentary spent a disproportionately small amount of time featuring Brown Asians (Filipinos, South Asians, Vietnamese, Hmong) or covering topics about Brown Asians. Only around 29.2% of the documentary involved Brown Asians even though they collectively compose approximately 55.1% of the Asian American population. The disparity is largest with South Asians, as only around 7.8% of the entire documentary involved South Asians but they compose 24% of the Asian American population.

Conclusion

So is the documentary a win for Brown Asian Americans? Based on this data, I don’t think so.

I sincerely like it, and I applaud all the folks involved in it. As well-intentioned as the creators may be, however, the documentary still ends up privileging East Asians and not giving Brown Asians fair treatment.

It must be acknowledged that it is almost an impossible task to cover all the communities under the very diverse Asian American umbrella, even in a 5-hour documentary. Indeed, as the series producer stated, the film is just a beginning.

I agree, and it is a very good one. But if we see it as a start, then we must have some goals to aspire to, even if they’re just intermediate ones.

Perhaps one goal can be to devote to Brown Asians what’s fair.

Brown Asians have been historically marginalized and forgotten within Asian America. Let’s stop repeating this history.