Mating

The Mating Strategies of Extroverts

Extroversion is linked to both short and long-term mating

Posted June 29, 2016

Evolutionary theories of human sexuality have tended to describe people as generally preferring either short or long-term mating strategies. Hence, the idea that human sexuality falls on a continuum where people at one end focus intensely on seeking opportunities for brief sexual liaisons, while those at the other end focus on committed long-term relationships. There is research suggesting that this one-dimensional view may be too simplistic because some people pursue both short and long-term mating simultaneously, while some people make little or no effort to pursue either. Hence, a multi-dimensional view of human sexuality may be more accurate. A similar issue occurs with theories that attempt to integrate mating strategies and features of personality into a single common factor based on life history strategy. Such theories also propose a one-dimensional continuum that encompasses a broad swathe of human characteristics, where people at one end have a fast life history strategy and those at the other end have a slow strategy. This theory also seems too simplistic because not all personality traits related to human sexuality fit neatly into a fast-slow continuum. Hence, a multi-dimensional view also seems more accurate.

According to life history theory, individuals tend to vary along a fast/slow continuum according to their preferred reproductive strategy. In this view, fast strategies are associated with high mating effort, that is, sexual promiscuity, while slow strategies are associated with higher parental effort, that is, commitment to long-term monogamous relationships (Figueredo et al., 2006). The idea behind this is that in harsh environments where life expectancy is relatively short and infant mortality is high, individuals will focus on having more offspring with reduced parental investment. On the other hand, in resource-rich environments, where life expectancy is longer and infant mortality is lower, individuals will focus on having fewer offspring and investing more intensively in each one. Life history theory was originally applied to understanding differences in animal species. Some species of mammals, e.g. elephants and the great apes, are relatively long-lived, tend to reproduce slowly, generally have only one infant at a time, and provide intensive parental care over a period of years; hence they are considered slow strategists. Other species, e.g. wolves, have relatively shorter life spans, tend to reproduce more frequently, give birth to multiple infants at the same time, and provide parental care over a relatively shorter period of time; hence they are considered fast strategists. One thing I find puzzling about this is the claim that slow strategies are supposed to be associated with monogamy, while fast strategies are associated with promiscuity and short-term mating. Short-term mating is relatively common in mammals, including elephants, where males provides no parental care at all. Although chimpanzees are clearly slow strategists compared to most mammals, they are also highly sexually promiscuous, and parental care is only provided by females. On the other hand, wolves are clearly fast strategists compared to elephants and chimpanzees, yet they form long-term monogamous bonds, and both parents provide care for their young. Hence, the idea that slow equals monogamy/fast equals promiscuity does not seem to fit the data very well at a species level.

Life history theory has been extended from differences between species to differences between individuals and even whole populations within the human species (Figueredo et al., 2006). As I have noted in a previous post, anomalies occur when applying the theory to human populations. Specifically, developing countries have relatively low life expectancy and high infant mortality compared to wealthier developed countries. Hence, one would expect people in poorer countries to be fast strategists, and people in wealthier countries to be slow strategists. However, cross-cultural data on attitudes towards short-term mating contradict the predictions of life history theory: people in poorer countries are less likely to indicate an interest in short-term mating compared to those in wealthier ones (Schmitt, 2005). Hence, monogamy may actually be more adaptive than promiscuity in harsh conditions, contrary to claims made by life history theory.

Life history theory has also been applied to personality traits (Figueredo, Vásquez, Brumbach, & Schneider, 2004). According to this view, which I have discussed in a number of posts, there is a broad factor of health and vitality known as the K-factor, that is associated with not only the fast/slow spectrum of reproductive strategies, but with a general factor of personality (GFP) that combines all the major traits in a socially desirable way.[1] Hence, individuals with a slow strategy should generally be high in a combination of traits such as extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience, while those with a fast strategy should exhibit low levels of these traits, along with high levels of antisocial traits including the Dark Triad of psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism. There is research to suggest that Dark Triad traits facilitate short-term mating and sexual promiscuity (Jonason, Li, Webster, & Schmitt, 2009; Jonason, Valentine, Li, & Harbeson, 2011). However, whether high levels of a GFP facilitate long-term mating has not been studied.

Recent research (Holtzman & Strube, 2013) suggests that life history theory may have another problem. The idea that sexual strategies fall along a one-dimensional continuum assumes that short-term and long-term mating are polar opposites. However, some people may prefer to pursue both kinds of strategies simultaneously, while some people do not pursue either. Hence, life history theory overlooks important human variations in sexual strategies. The study by Holtzman and Strube examined the relationships between the two mating strategies and a number of personality traits including the Big Five and the Dark Triad in two different cultures: one Western (the USA), and one Eastern (India). They found that measures of long-term mating (i.e. experience with long-term relationships) and of interest in short-term mating (e.g. comfort with and desire to have uncommitted sexual affairs) had only a moderate negative correlation in the American sample (r = -.23), and a somewhat larger negative correlation in the Indian sample (r = -.54). This showed that although there is a general trend for people to have a preference for either long or short-term mating, the two preferences are far from mutually exclusive. The results for personality were also quite interesting. As expected, the Dark Triad traits were all positively associated with interest in short-term mating, while psychopathy and Machiavellianism were negatively associated with long-term mating (narcissism was unrelated). Additionally, agreeableness and conscientiousness were negatively associated with interest in short-term, and positively associated with long-term mating. The finding I found most interesting was that in the American sample, extraversion was positively correlated with both short and long-term mating. In the Indian sample though, extraversion was positively correlated with short-term and unrelated to long-term mating. Extraversion being positively related to both short and long-term mating (at least in one culture) is difficult to explain within a one-dimensional view of reproductive strategies, but is readily accommodated by a multi-dimensional view in which short and long-term strategies are to some degree independent of each other.

These findings on extraversion are in accordance with past research linking personality with various dimensions of sexuality (Schmitt & Buss, 2000). For example, high extraversion has been linked to lack of relationship exclusivity and erotophilia (i.e. an open, accepting, guilt free attitude towards sex) – things that seem to facilitate short-term mating – yet also with emotional investment (being loving, romantic, and affectionate), something that would seem compatible with long-term mating as well.

According to Holtzman and Strube, extraversion might facilitate a dual relationship strategy, at least in some cultures, where a person aims to balance the benefits of being in a long-term relationship with the excitement of having short-term affairs on the side. This might help shed some light on why some people in committed long-term relationships are frequently unfaithful . Extraversion has been linked to an underlying sensitivity to rewarding experiences of all kinds, not just with sexuality but also with alcohol and recreational drug use (Cook, Young, Taylor, & Bedford, 1998; Miller et al., 2004), as well as to interpersonal effectiveness in general. Hence, it would make sense that extraversion may be linked to a relationship strategy of trying to have as many rewards as possible, even when these involve conflicting interests. Traits related to extraversion have also been linked to risk-taking (e.g. risky sex and drug use) (Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000), thought to be a feature of fast life history strategies. Yet high extraversion is supposed to be linked to high levels of a general factor of personality, (and therefore with slow strategies) due to its association with social effectiveness. Consequently, extraversion combines both socially desirable and undesirable qualities, and is not clearly associated with either end of the proposed K continuum.

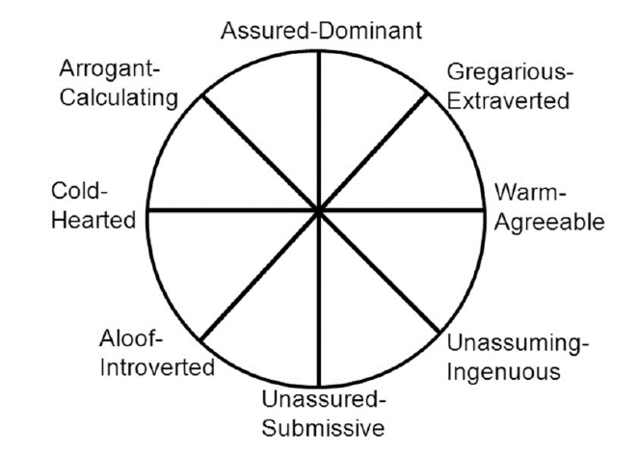

The idea that short-term and long-term mating are not mutually exclusive is difficult to reconcile with one-dimensional models such as life history theory, and the general factor of personality. However, it is clearly compatible with multi-dimensional models. Holtzman and Strube suggest that short-term and long-term mating may map roughly onto the interpersonal circumplex. This model features two dimensions of interpersonal behavior known as agency (getting ahead and attaining social status) and communion (getting along with others and maintaining warm relationships). Long-term mating may be aligned particularly with communion, while short-term mating might align particularly with agency. Interestingly, the combination of high agency and high communion is associated with extraversion, while a combination of lower agency and high communion is most associated with agreeableness. This makes sense in the light of Holtzman and Strube’s findings that agreeableness was positively associated with long-term mating and negatively associated with short-term mating, while extraversion was positively associated with both (at least in the USA).

It would be interesting to look at the relationships between personality traits, particularly extraversion, with long-term mating in a wider range of cultures. One large study (Schmitt & Shackelford, 2008) found that interest in short-term mating and promiscuity were associated with higher extraversion and with lower agreeableness and conscientiousness across many regions of the world. However, the study by Holtzman and Strube is the first one to look at the relationship with long-term mating in different cultures. They found different relationships between extraversion and long-term mating in India, a collectivistic non-Western culture, compared to the highly individualistic USA. Perhaps, extraversion is associated with long-term mating mainly in Western cultures, where individualism is highly valued. Western cultures generally tend to be more permissive than most non-Western ones. It is possible that permissive societies facilitate mixed reproductive strategies, allowing some people to have things both ways when it comes to sex, while more conservative and traditional cultures might suppress such tendencies more strongly.

Footnote

[1] To be fair, some proponents of life history theory (Dunkel, Cabeza De Baca, Woodley, & Fernandes, 2014) have argued that life history strategy and a general factor of personality are quite distinct from each other and that the latter is not a good proxy for the former, although they claim that both are components of what they refer to as a “super-K factor.”

Image Credits

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli (1485). Source: Wikipedia

Bonobo mother Lana, age 25, and daughter Kesi, 2, at the San Diego Zoo in 2006. Credit: W. H. Calvin Ape Bonobo San Diego Zoo. Source: Wikipedia, licensed under Creative Commons.

La Belle Dame sans Merci by John William Waterhouse (1893). Source: Wikipedia

The diagram of the Interpersonal Circumplex originally appears in: DeYoung, C. G., Weisberg, Y. J., Quilty, L. C., & Peterson, J. B. (2013). Unifying the Aspects of the Big Five, the Interpersonal Circumplex, and Trait Affiliation. Journal of Personality, 81(5), 465-475. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12020.

References

Cook, M., Young, A., Taylor, D., & Bedford, A. P. (1998). Personality correlates of alcohol consumption. Personality and Individual Differences, 24(5), 641-647. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00214-6

Dunkel, C. S., Cabeza De Baca, T., Woodley, M. A., & Fernandes, H. B. F. (2014). The General Factor of Personality and general intelligence: Testing hypotheses from Differential-K, Life History Theory, and strategic differentiation–integration effort. Personality and Individual Differences, 61–62(0), 13-17. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.017

Figueredo, A. J., Vásquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., & Schneider, S. M. R. (2004). The heritability of life history strategy: The k‐factor, covitality, and personality. Social Biology, 51(3-4), 121-143. doi:10.1080/19485565.2004.9989090

Figueredo, A. J., Vásquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., Schneider, S. M. R., Sefcek, J. A., Tal, I. R., . . . Jacobs, W. J. (2006). Consilience and Life History Theory: From genes to brain to reproductive strategy. Developmental Review, 26(2), 243-275. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.002

Holtzman, N. S., & Strube, M. J. (2013). Above and beyond Short-Term Mating, Long-Term Mating is Uniquely Tied to Human Personality. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(5). doi:10.1177/147470491301100514

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The dark triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men. European Journal of Personality, 23(1), 5-18. doi:10.1002/per.698

Jonason, P. K., Valentine, K. A., Li, N. P., & Harbeson, C. L. (2011). Mate-selection and the Dark Triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy and creating a volatile environment. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(6), 759-763. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.025

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D., Zimmerman, R. S., Logan, T. K., Leukefeld, C., & Clayton, R. (2004). The utility of the Five Factor Model in understanding risky sexual behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1611-1626. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.06.009

Schmitt, D. P. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: a 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 247-311.

Schmitt, D. P., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Sexual Dimensions of Person Description: Beyond or Subsumed by the Big Five? Journal of Research in Personality, 34(2), 141-177. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1999.2267

Schmitt, D. P., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Big Five traits related to short-term mating: From personality to promiscuity across 46 nations. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(2), 246-282. doi:10.1177/147470490800600204

Zuckerman, M., & Kuhlman, D. M. (2000). Personality and Risk-Taking: Common Bisocial Factors. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 999-1029. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00124