Identity

Ideological Identity Adds Fuel to Political Disagreements

Viewing oneself as liberal or conservative can foster partisan animosity.

Posted November 27, 2018

Research in political science shows that Republicans and Democrats are more divided along ideological lines than at any time in the past 25 years. Not only do they disagree strongly about many issues, but antipathy between the two parties is stronger and more apparent than in recent memory. In part, this partisan mistrust and animosity is fueled by genuine differences in beliefs, attitudes, and policy preferences. Yet, recent research shows that political divisions in the United States are based on more than mere differences of opinion.

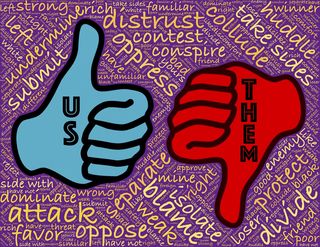

One of the most striking discoveries in social psychology involves how little it takes to lead members of different groups to come into conflict with each other. Often, merely the existence of two groups is all that’s needed to create favoritism toward one’s own group and hostility toward the other group. People sometimes dislike and disadvantage one another simply because they view themselves as members of groups that stand in opposition to one another. Their social identity as members of a group is enough to generate and maintain conflict.

In the 1970s, Henri Tajfel and his colleagues introduced the “minimal group paradigm” to study the conditions under which the members of a group will discriminate against another group. Tajfel planned to create laboratory groups that were so artificial that their members would not show the characteristic tendencies toward in-group favoritism and out-group hostility seen in real groups. With these minimal groups as a baseline, the researchers hoped to study the factors that lead groups to come into conflict with one another.

Unfortunately, the researchers hit a snag. They found that it was impossible to create a group that was so artificial and minimal that its members did not show in-group favoritism. No matter how trivial the basis on which members were assigned to their respective groups, the members began to favor their own group and discriminate against the out-group. Even when assigned to groups at random or on the basis of some meaningless criterion, participants almost always showed in-group favoritism. And, group members displayed an in-group bias even if they never met one another and didn’t know who the other members of their group were! All that was required to create conflict was for people to perceive themselves to be members of different groups.

Lilliana Mason, a political psychologist at the University of Maryland, recently took these findings a step further to examine the animosity that exists between political liberals and conservatives in the United States. Most of us assume that our feelings about people who fall at the other end of the political spectrum are based on the fact that they have different beliefs and attitudes than we do. But, given what we know from the minimal group studies, it’s possible that merely identifying oneself as a liberal or conservative also plays a role.

To test this hypothesis, Mason measured people’s attitudes regarding controversial issues such as immigration, abortion, the Affordable Care Act, and gun control, as well as the degree to which they identified themselves as liberal or conservative. Then, Mason assessed the degree to which participants indicated that they wanted to maintain social distance from people who fell in the other ideological group. Specifically, she asked participants how willing they would be to live next door to, be friends with, spend occasional social time with, and marry someone who was from the other political category.

You might imagine that whether people regard themselves as liberal or conservative is merely a shorthand description of their beliefs about political issues. But, consistent with other research, Mason found that the relationship between political identity (liberal-conservative) and beliefs about political issues was actually rather small. In other words, identifying oneself as a liberal or conservative is not strongly linked to people’s beliefs about the issues. Both liberals and conservatives show a great deal of within-group diversity in their beliefs (more so for conservatives), and self-identified liberals and conservatives are not as different in their beliefs overall as the labels might suggest.

Even so, Mason found that desired social distance from members of the other ideological group was more strongly predicted by whether people identified themselves as conservative or liberal than whether they actually held “conservative” or “liberal” attitudes. In fact, identity-based ideology – whether people indicated they were liberal or conservative – was twice as important in predicting social distance from ideological out-group members than people’s actual political beliefs. As Mason observed, “Americans are dividing themselves socially on the basis of whether they call themselves liberal or conservative, independent of their actual policy differences.”

These findings may provide a few hints for how we can lower the enmity of our political conversations. First, we should remember that most people’s political views do not fit a consistent, coherent pattern that is unambiguously “liberal” or “conservative.” For example, a voter might easily be pro-life, support gun control, and be middle-of-the-road about the Affordable Care Act. Furthermore, research shows that most Americans are actually political moderates rather than distinctly liberal or conservative, although this proportion is lower than it once was. It is important for each of us to acknowledge the complexity of our own political views and to recognize that identifying ourselves with a single label – liberal or conservative – probably misrepresents what we believe to some extent. And, whatever your beliefs, why turn your preferences for particular government policies into an identity?

Labeling other people as “liberal” or “conservative” is counterproductive for the same reason. Your seemingly “conservative” neighbor may, in fact, agree with your liberal views on particular issues, or your seemingly "liberal" uncle may share your conservative views in certain areas. Understanding that we aren’t different types of people who fall neatly into one box or the other – but rather people with different patterns of specific beliefs – reduces the perceived differences among us. Using broad labels such as "liberal" and "conservative" masks the things that we have in common.

Finally, focusing our political conversations with one another on specific policy issues rather than on broad liberal-versus-conservative debates should reduce the degree to which our ideological identities enter the fray. It's easier for us to talk calmly about our disagreements about particular issues than to approach our interactions with the assumption that people in the other ideological camp are wrong about everything.

References

Mason, L. (2018). Ideologues without issues: The polarizing consequences of ideological identities. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82, 280-301.