Psychology

What It Means to Be a Human Person

It is time we get clear about the ontology of personhood.

Posted December 10, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Christian Smith's excellent book, "What is a Person?," clearly spells out an ontology of human persons for sociology.

- The Unified Theory gives a clear ontology of the mental that directly aligns with Smith's view of human persons.

- There is now a clear bridge from psychology into sociology that clarifies the ontology of both mental behavior and human persons.

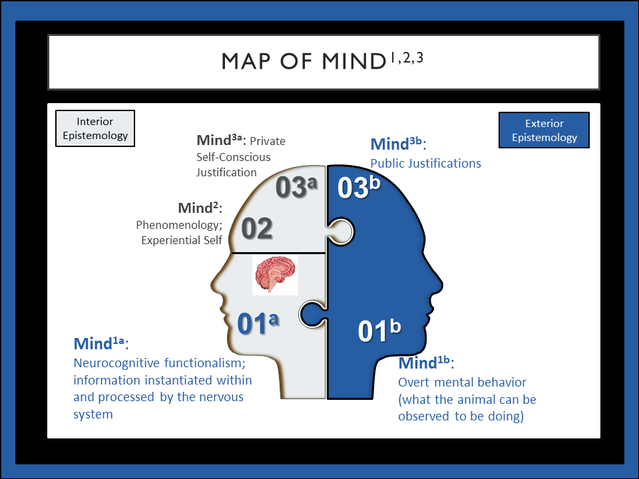

A central feature of the Unified Theory of Knowledge (UTOK) is that it affords us a way to scientifically frame the ontology of the mental (see here for this argument in detail). Via the Tree of Knowledge System, it shows how "mental evolution" began with the evolution of animals with nervous systems and complex active bodies during the Cambrian Explosion approximately 550,000,000 years ago. In addition, it clearly defines the mental behaviors of "minded animals" as consisting of sensory-motor looping functions that allow animals to develop paths of behavior investment via recursive relevance realization that produce a functional effect on the animal-environment relationship. Moreover, via the Map of Mind1,2,3, UTOK specifies why there are three domains of mental behavioral processes that must be differentiated, both ontologically and epistemologically.

The domain of Mind1 refers to the domain of covert neurocognitive processes (Mind1a) that regulate the overt mental behavioral activities that are observable to others (Mind1b). Mind2 refers to the subjective conscious experience of being in the world and it is only directly observable from the inside, that is from the subjective perspective of the animal. Mind3 is present in human persons and refers to the self-conscious justification processes that take place within the individual's subjective field of experience (Mind3a) or between people in the form of verbal expressions to others (Mind3b).

Getting clear about the ontology of the mental is necessary to solve the problem of psychology. And this is a necessary step to link psychology to the social sciences. Indeed, it is at the intersection between psychology and the social sciences (as well as humanities and philosophy) that we find one of the most central problems in the academy, which pertains to the question of what is a person? This question is directly taken up in Professor Christian Smith’s excellent work, What Is a Person? Rethinking Humanity, Social Life and the Moral Good From the Person Up.

Smith tackles this perspective from the vantage point of critical realism and personalism. Critical realism is the philosophy of science developed by the visionary Roy Bhaskar It can be thought of as developing a synthetic, "metamodern" philosophical position that effectively bridges between modernist scientific traditions that emphasize analytic truth claims and postmodern critical positions that emphasize the social construction of knowledge. That is, critical realism effectively works to clarify both the process by which humans socially construct knowledge (i.e., epistemology) and the scientific reality of nature as stratified levels of complexity (i.e., ontology). Smith combines this with personalism, which he acknowledges is less easy to summarize as a clear statement. He characterized personalism as a broad school of thought and collection of thinkers that enables us to emphasize the reality of human lived experience and human dignity. Smith puts the issue as follows:

The central idea in personalism that is relevant for my argument is deceptively simple. This is the belief that human beings are persons.

At first, this might sound silly as it seems self-evident and thus might appear to be akin to saying something like dogs are canines. But it is not. In fact, it is very consequential because persons are a particular kind of thing. Indeed, a central insight from UTOK’s analysis of the mental and the difference between animal-mental behavior and human mental behavior is the conclusion that humans are both primates and persons.

The question thus emerges regarding what Christian means by a person. Through a long series of detailed and powerful arguments, Christian delineates how personhood has emerged in evolutionary and social history and consists of a long list of intersecting capacities. Ultimately, he comes to define persons as follows:

By person I mean a conscious, reflective, embodied, self-transcending center of subjective experience, durable identity, moral commitment, and social communication who—as the efficient cause of his or her own responsible actions and interactions—exercises complex capacities for agency and intersubjectivity in order to develop and sustain his or her own communicable self in loving relationships with other personal selves and the nonpersonal world.

Smith’s analysis of the ontology of human persons is remarkably consistent with UTOK’s analysis of the ontology of the mental, from the animal into the human, and then into the emergence of the Culture-Person plane of existence. Indeed, I have argued repeatedly that the key to understanding humans from a scientific perspective grounded in a coherent ontology is to see them as primates that are organized by the two metatheories of Behavioral Investment Theory and the Influence Matrix and as persons, which is framed by Justification Systems Theory. Justification Systems Theory provides a framework for understanding the emergence of the domain of Mind3 and the Culture-Person plane of existence. It aligns remarkably well with Smith’s analysis.

Importantly, Smith is a sociologist, not a psychologist. Indeed, his book has almost no psychology in it at all. Rather the book positions his argument for the ontology of human persons in relationship to other traditions in sociology, such as social constructionist traditions, network structuralist positions, and variable aggregate analyses. As such, we have a strong, independent, convergent argument, when the two positions are placed side by side.

According to the UTOK, the Enlightenment failed to produce a clear framework for understanding the proper relationships between matter and mind and science and social knowledge. This is called the Enlightenment Gap. It resides at that center of our modern state of chaotic fragmented pluralism. This gap means that we cannot go from our relatively coherent knowledge in the physical and biological sciences into the psychological and social sciences. Although he did not directly call it as such, the gap was nevertheless very well seen by Edward O. Wilson in his important book, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. He described it as follows (p. 126):

We know that virtually all of human behavior is transmitted by culture. We also know that biology has an important effect on the origin of culture and its transmission. The question remaining is how biology and culture interact, and in particular how they interact across all societies to create the commonalities of human nature. What, in the final analysis, joins the deep, mostly genetic history of the species as a whole to the more recent cultural histories of far-flung societies? That, in my opinion, is the nub of the relationship between the two cultures. It can be stated as a problem to be solved, the central problem of the social sciences and the humanities, and simultaneously one of the great remaining problems of the natural sciences.

At present time no one has a solution. But in the sense that no one in 1842 knew the true cause of evolution and in 1952 no one knew the nature of the genetic code, the way to solve the problem may lie within our grasp.

Another way of saying this is that the Enlightenment left us with a gap in scientifically understanding the ontological evolution of the animal mental into human persons and modern societies. This is why we cannot clearly trace the ontological trail from biology into the animal mind into a clear map of human mental behavior and the assemblages of societies.

UTOK’s frame affords us a way to bridge and resolve the Enlightenment Gap. Most importantly, it affords a coherent naturalistic ontology for the animal-mental into the culture-person plane of existence. Put differently, via its unified theory of psychology, UTOK bridges the gap from ethology and cognitive-behavioral neuroscience into human psychology. This "human psychology" sits at the base of the social sciences and frames human mental behavior.

What is so encouraging about Christian Smith’s work is that it shows how we can pick up the baton of understanding from human psychology and place it directly at the base of sociology, and from there advance into the social sciences that study large-scale social systems. Success in this means that the stage is being set for our capacity to resolve the Enlightenment Gap. This will enable us to start moving toward a second Enlightenment that gives rise to a scientific understanding of a coherent naturalistic ontology that is well situated to revitalize the human soul and spirit in the 21st century.