Freudian Psychology

Understanding the Defensive System

The basics of the defensive system.

Posted September 13, 2015

"That is not what I said!" I protested. My wife had just reported to me, in a somewhat accusing tone, that something I had said had hurt my daughter's feelings.

"I did bring it up, but that was not what I meant," I explained.

"Well, that was the way she heard it, and she was hurt and pissed," my wife went on.

"Well, you know she is a bit sensitive about this issue," I declared, reasserting I had been justified in what I had done.

This brief exchange occurred the other day. The process elements here are likely so common that you recognize the dynamics without needing to know the content. It is also the case that after some time and reflection, I realized that actually I had said it pretty much exactly the way my wife accused me of. Yet, in the context of being accused, my immediate reaction was to defend myself and imply the issue resided with my daughter's hypersensitivity.

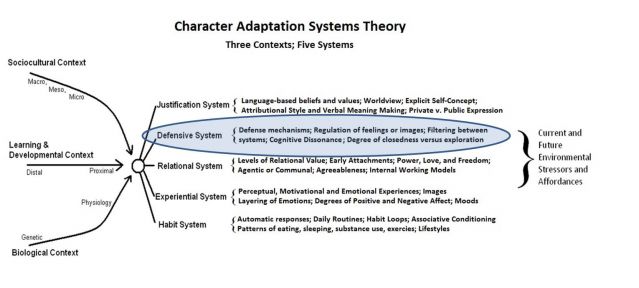

The goal of this blog is to help you get clear about the ingredients that make up the psychological defensive system. According to Character Adaptation Systems Theory (CAST), humans have five systems of psychological adaptation, one of which is the defensive system. Whereas the other four systems (habit, feeling/experiential, relational, and justification) are pretty easy to identify, the defensive system is more difficult to definitively nail down. Indeed, psychologists of various stripes have adopted an enormous number of positions on the concept, ranging anywhere from psychological defenses being central to almost every aspect of human functioning (e.g., Freud) to them being dismissed as too nebulous a concept to be useful (e.g., Watson). In a recent review of the concept of psychological defense, Hart proclaimed that, even today, “ambiguity reigns” and there is much debate and disagreement about the fundamental nature of the concept.

Rather than review the debate and provide a historical context, I am simply going to explain the defensive system from the vantage point of the Unified Theory. First, I will describe “where” it is relative to other systems of adaptation and in our map of human consciousness. Then I will describe what it is that people are usually defending against. Then I will describe why the defensive system functions the way it does. Finally, I will articulate what are the various ingredients that make it up.

Where does the defensive system reside?

To get clear about what I mean by the defensive system, here is a CAST diagram with the defensive system circled. Notice the placement of the defensive system. It resides “above” the habit, experiential and relational systems. These are “sub-self-conscious” systems, which mean they (often) operate beneath or without full self-conscious awareness.

These systems correspond to Freud’s “unconscious” (for Freud, consciousness referred to self-reflected reasoned awareness, rather than phenomenological experience). The defensive system is below the justification system, which corresponds to reflective self-consciousness.

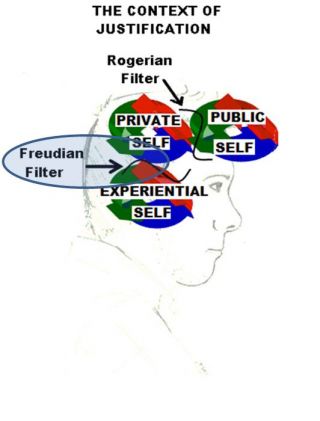

Here is a map of human consciousness to be clear on what I am talking about. The unified approach delineates three domains of consciousness: 1) Experiential (the theater of experience); 2) Private Self (your narrator and seat of agency); and 3) Public self (the image you attempt to convey and way you say publicly). In addition, there are filters between these domains. Highlighted here, the Freudian filter exists in between experiential consciousness and Private self-consciousness. The Freudian filter corresponds directly with the defensive system, such that the two are almost synonymous (the defensive system is just a bit broader, and includes more than just filtering).

What is it that people are defending against?

As the example that started this blog suggests, people are motivated to maintain certain states. For example, because I have an identity as a "good father" I am motivated to resist accusations that I am insensitive and would hurt my daughter's feelings. Thus, my initial rejection of the accusation was in part because my defensive system got activated.

There are a number of things that people are defended against, but we can identify five broad domains, including: 1) Death and the idea of death; 2) threats to one’s worldview and meaning making systems; 3) threats to one’s relationships with others; 4) threats to self-esteem or self-concept (i.e., one's ego); and 5) painful feelings, scary impulses, or traumatic memories.

From the vantage point of the unified theory, the justification system seeks “equilibrium” such that the individual is in a “justified state of being”. A justified state of being is one that is secure and legitimate. When my wife accused me of being insensitive, this was an unjustified state of being and, almost reflexively, I challenged it. After a while, I reflected, and ultimately restored equilibrium by acknowledging that in this instance I was insensitive, and I was sorry because that was not the way I normally am.

Why does the defensive system work the way it does?

The first big idea I had in what would ultimately become the Unified Theory was ‘the Justification Hypothesis’, which placed Freud's key observation about humans as a rationalizing animal on a sound evolutionary base. (For a full length chapter on the JH, see here). The JH leads to the idea that the self-consciousness system, at least in part, functions in social settings much like a defense attorney, especially in times of conflict, uncertainty, or insecurity. A defense attorney, of course, biases and filters information with a goal in mind. In this case, the goal is a justifiable state of being (defined as a meaningful narrative in which one is secure and legitimate--being accused means that you are not secure or "legitimate"). This framework is consistent both with modern work in cognitive dissonance and modern psychodynamic theory. As Swanson said in his book Ego Defenses and the Legitimization of Behavior, we can think of all ego defenses as “justifications that people make to themselves and to others—justifications so designed that the defender, not just other people, can accept them”.

How does the defensive system work?

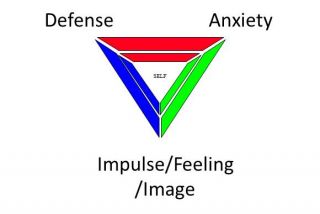

The defensive system works via two major processes. First there is the inhibiting filtration of information, images, impulses or feelings that would result in an “unjustified” state of being. The map for this inhibition is well capture by the Malan Triangle of Conflict (below), whereby the base of the triangle represents the feeling, image, impulse which in turn elicits anxiety, which then causes defense, usually in the form of experiential shifts to avoid the anxiety producing material and redirect attention elsewhere. This process is called repression by psychodynamic folks and experiential avoidance by folks of a more behavioral inclination (e.g., as in ACT). Other examples of inhibiting filtration processes are denial, suppression, and compartmentalizing. (See here for a description of common defenses--although note that I don't think all psychodynamic defense mechanisms are correctly described as such. Some, such as regression and acting out, can be reframed as a failure of defense mechanisms).

The second major process is the more active construction of justifications that allow aspects of the material into awareness, but the meaning is altered such that it is no longer as dangerous or disruptive. This is the process of rationalizing, intellectualizing, minimizing and so forth.

There are also structural elements in the justification system that enable it to maintain consistency, coherence, and security. For example, there are fairly automatic self-serving attributional processes that operate, such that if something bad happens, the tendency is to develop causal attributions outside the self, whereas if something good happens, the tendency is to be more inclined to make personal attributions (e.g., when we fail the test, it was because it was unfair, when we ace it, it was because we are smart). Here are some additional blogs on this topic:

Understanding-our-justification-systems

The-forces-and-filters-self-knowledge

When are defensive processes adaptive and when are they maladaptive?

A basic principle of the Unified Theory is that justification systems require at least some equilibrium (meaning coherence and consistency) to function. In order for people to function optimally in the social world, it is valuable that the individual has a generally positive view of themselves that is also grounded in reality or some emphasis on accuracy. Indeed, research on self-concept, biasing and dissonance points to the idea that, broadly speaking, the most “ideal” social position is to bias information towards one self and important others in the most positive way that can be justified. This suggests that some defensive biasing is adaptive.

In addition, we can think about defenses being adaptive in terms of helping folks regulate intense emotions without becoming debilitated. For example, one of the more difficult events in my life was when I left my back door open and my dog Spencer got out and later I found him on the side of the road. For about an hour after that, I was in a bit of a shock. As I drove down to where my wife worked and told her, as I drove to the vet, and as made preparations for his burial I was calm and hyper-regulated. Then, right after I called into the restaurant where I worked and told them I could not come in, as soon as I hung up the phone, I burst into tears. The defense against the pain was adaptive in the sense that it allowed me to get my stuff in order before I collapsed into grief.

Of course, defenses also have maladaptive elements. One of the most troubling aspects is that they generally operate outside of awareness, thus we often can’t assess them. Second, by definition, they blind and bias information available to our self-consciousness, thus when our defenses are operating we are not operating from a full deck, which makes us vulnerable to being blindsided. Further, they are often effective in reducing anxiety in the short term, but create long-term problems because they often orient us to avoid key issues. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, defenses create static in relationships (see the above for an everyday example). Anyone who has been in a close relationship with someone who is defensive about something (and who has not?) knows that the experience can be enormously frustrating.

One of my large scale goals is to increase psychological mindedness in our society. One of the most crucial things to understand to achieve this goal is to foster understanding of the defensive system. So, next time you are feeling more like an attorney in a relationship, take some time to reflect and get clear on what might be driving that, how and why.