Philosophy

The Tree of Knowledge System

The first piece of the unified theory

Posted December 17, 2011

"Look, Daddy! I drew your work!" I looked down to see a picture that warmed my heart both as a father and as the developer of the Unified Theory. At the age of four, my daughter Sydney was presenting me with the picture shared here. "See," she said, "Rocks, plants, animals, people." That my daughter was able to so quickly grasp these categories is really not all that surprising. Work from cognitive developmental psychologists strongly suggests that humans are intuitively prepared to categorize the world into these groups. Yet while virtually all human societies, and many great thinkers like Aristotle, see these four categories in nature, science has consistently debunked the ideas people have generated about the fundamental differences between these categories and instead has tended to emphasize an underlying continuity. Plants do not have a vitalistic life force that makes them grow, but instead are made up of cells, which in turn are made up of molecules. Complex animal behaviors are the product of the brain, which is made up of cells, which are made up of molecules. And humans don't have a soul, but instead they evolved from animals, and their unique form of consciousness comes from language and their big brains.

So which is it? Are their fundamental categories in nature with clear dividing lines? Or does nature simply exist on a continuum of complexity, with no fundamental breaks? The Unified Theory says, paradoxically, that the answer is both. And one of its key pieces, the Tree of Knowledge System, shows how.

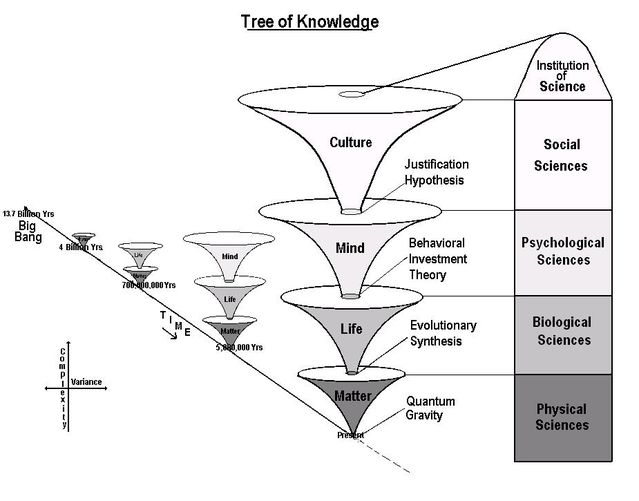

The Tree of Knowledge (ToK) System is a map of cosmic evolution (click here to go to the ToK Website and here to read about it on Wiki). Cosmic evolution refers to the changes that have taken place in the universe since the Big Bang that have resulted in the incredibly diverse and complex entities that exist today. Specifically, the ToK System characterizes the universe as an unfolding wave of Energy-Information that began as a pure Energy singularity 13.7 billion years ago.

Although many have offered a similar conception, it is nonetheless the case that the ToK System is a new map-one that clearly resolves the continuity versus discontinuity conundrum. The way it does so is via the depiction of the universe as four distinguishable dimensions of complexity. Virtually all other similar models depict the hierarchy of nature as a single dimension of complexity that stretches from subatomic particles to molecules to organisms to human societies (emphasizing the continuity). In contrast, with its claim that the universe is an unfolding wave of Energy-Information, the ToK System argues the emergence of novel information processing systems have resulted in fundamental phase shifts and, because of this, the higher dimensions of complexity are not reducible to the dimensions beneath them.

The ToK System posits that there are four dimensions of complexity: 1) Matter; 2) Life; 3) Mind; and 4) Culture. Why are there four (instead of 3 or 5) such dimensions? Because following the emergence of Matter from Energy, three separate information processing systems have evolved. First, about four billion years ago, genetic information processing systems evolved, giving rise to the dimension of Life. Second, approximately 600 million years ago, neuronal information processing systems evolved, giving rise to the dimension of Mind. Third, approximately 100,000 years ago, symbolic information processing systems evolved (aka language), giving rise to the dimension of Culture. (Note, if you are wondering about computers, you are getting the hang of thinking this way...computers may well represent the beginnings of a new phase transition!).

These dimensions of complexity are different dimensions of causality, which is a rather profound philosophical argument. To see why, consider that Descartes' philosophical analysis is famous for its dualism. Matter and mind were conceived by Descartes as separate spheres of substance and cause. In contrast, modern scientific views have generally argued for a monistic position. Mind must be some form of matter because the problem of nonmaterial causality is philosophically insurmountable. The ToK System is monistic in the sense that the higher dimensions of complexity supervene on the lower dimensions. By that I mean that everything that is biological is also physical, everything that is psychological is biological, and so forth, with Energy being the ultimate common denominator. But the ToK System is not greedily reductionistic. Everything is not just energy and matter, and biology, psychology and the social sciences cannot be reduced to physics because there are fundamentally different dimensions of complexity.

How is the Tree of Knowledge System related to a general Theory of Knowledge (TOK)? It is essential because it provides a macro-level view of the key elements of the universe, and defines the key elements and shows how they exist in relationship to one another. The ToK System also provides a framework for situating human knowledge (Culture) in relationship to the rest of the universe.

But how is the ToK System relevant to defining the field of psychology? Well, that has been the primary focus of my writings. In the first paper I wrote on the ToK System, I emphasized the points between the dimensions, what I called "joint points". Two of the other three pieces of the Unified Theory are joint points. One, called Behavioral Investment Theory, is the joint point between Life and Mind, meaning that it provides a causal explanatory framework for explaining animal (or mental) behavior. The other is called the Justification Hypothesis, which is the joint point between Mind and Culture, and provides a causal explanatory framework for the emergence of human self-consciousness and culture. These pieces of the unified theory will be the subject of my next two posts.