Bias

Transforming Schools to Promote Anti-Racism

We cannot overcome racism within the conventional schooling structure.

Posted August 27, 2020

As I wrote in a previous post, the scourge of anti-Black racism is on center stage in American society. Many activists and commentators have noted that if we are to defeat racism, simply being non-racist is insufficient. We must be engaged in anti-racism and actively work to dismantle prejudice. This is a multi-faceted undertaking, and every institution must confront its own biases. These may not always involve violence, but could include harassment/bullying, discrimination in learning or job opportunities, and low representation of people from minority groups which can distort our quest for knowledge.

Fortunately, I am sensing a groundswell of support for anti-racism in academic circles. For example, at the University of Maryland where I work as a faculty member, my colleagues Nazish Salahuddin and Monica Kearney led a summer workshop and discussion series called “Advancing Anti-Racist Education,” which was open to faculty across campus. In these sessions, we discussed how to incorporate anti-racism into our work by making substantive changes to our teaching. This can include modifying syllabus language, changing classroom norms, infusing anti-racist goals into coursework and assignments, and promoting BIPOC scholars. Essentially, these actions involve ways that individual academics can positively change practices such that anti-racism permeates their work. I fully support this approach.

But on reflection, I wonder if dispersed individual actions are enough to change deep-rooted institutional traditions and culture?

This is something I’ve thought a lot about in the context of the environmental movement and the fight against climate change. Many activists encourage individuals to change their lifestyles to reduce their carbon footprints (e.g., eating less meat, using energy-efficient appliances, traveling less). But individual actions stop short of the larger goal to reverse climate change. Even in the context of lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic which created large reductions in our individual energy consumption, carbon dioxide levels in our atmosphere are the highest they’ve ever been. In order to truly stop climate change, we need wide-scale solutions (like carbon pricing) as a means to decarbonize our entire economy. Climate change won’t be stopped until we replace fossil fuel energy with alternative energies (like solar or wind energies) on an enormous scale. This requires mass coordination across all levels of society.

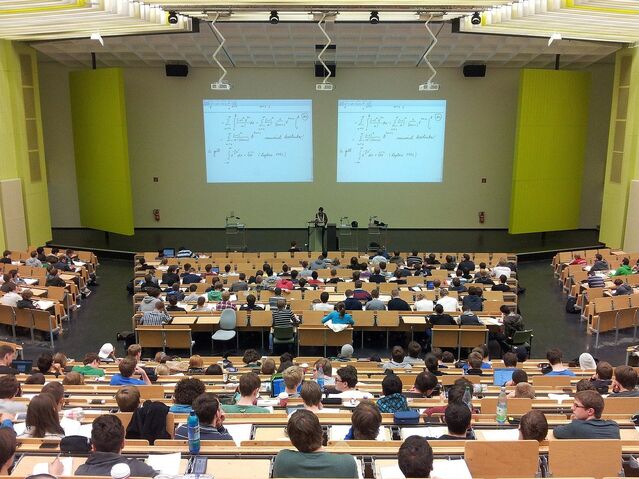

I think the same type of mass coordination is necessary if we are to achieve anti-racist and anti-fascist goals in academia. Positive actions from individual faculty are necessary but insufficient to achieve real momentum shifts. Addressing structural racism involves rethinking and reforming every aspect of higher education. This includes the conventional schooling structure that involves standardized learning outcomes, mandatory coursework, high stakes exams, and letter/number grades. Such a system de-emphasizes the motivational curiosity that is essential not only for deep learning but also for creativity/innovation, well-being, and a functioning society. As others have written before, the aspirational model for school relies on students’ genuine academic interests. When students are motivated by curiosity (which cannot possibly be forced), then they are driven to make the world a better place. But when the system incentivizes students to work towards maximizing their credentials, then they are driven by competitive self-interest, and social progress cannot be realized.

We can all take individual actions to make change if we want. For instance, in terms of classroom norms, I tell my students to address me by my first name and invite them to talk with me about any topic they’re interested in (like sports or TV shows)—essentially, to treat me like a peer. This empowers students to question what they’re told and to think critically about information and institutions. But other instructors may want students to address them by their formal title “Dr.” or “Professor” followed by their last name, thereby reinforcing a social hierarchy, and confine their conversations with students to focus only on course content. Such practices restrict learning and disempower students, but there are no formal institutional rules against them.

I can also voice concerns among fellow faculty and administrators that student evaluations of teaching do not correlate with learning outcomes and so we should be skeptical about what they truly measure. In many cases, these are fraught with racial and gender biases. But colleges and universities still use them as performance indicators, and they play a major role in hiring, merit pay, promotions, and awards.

I can also advise my students that grades don’t matter as much as they think, and they should focus on the value of learning for its own sake. But students are keenly aware that employers or grad/med schools are looking at their GPAs, so they act like anything less than an A++ is a tragic failure. If perfectionism is a symptom of white supremacy, then this kind of unrealistic standard for success can only be fixed by dismantling the entire grading taxonomy. We cannot possibly preserve a system in which students are competing with each other for a .1% edge in GPA, class rank, or Latin honors, while at the same time hoping to eradicate racism. It’s simply not possible. Anti-racist pedagogy should be unbounded by antiquated traditions like transcripts, where students’ learning is artificially reduced to mere numbers.

Instead, the anti-racist movement can embrace alternative forms of education that involve pure freedom of academic inquiry, curiosity, love of truth, and respect for dissent, such as the models outlined by scholars like Nikhil Goyal, Peter Gray, Susan Blum, and others. In democratic schools, students take charge of their learning, and the institutional structures hold them on equal footing with faculty, staff, and administration. It is in this type of environment that colleges and universities will truly be vehicles for social change and racial progress.

In sum, we should continue conversations that involve individual actions, but true progress will only happen when we strive for institutional reforms at all levels of academia. In particular, I think the best way to achieve our anti-racist and anti-fascist goals in the context of school is to transform the learning environment to be egalitarian, where students and personnel perceive each other as social equals. We must liberate ourselves from the constraints of conventional schooling and set our minds free.