Health

All the Pain We Cannot See

Part I: The hidden costs of social distancing and lockdowns.

Posted April 2, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

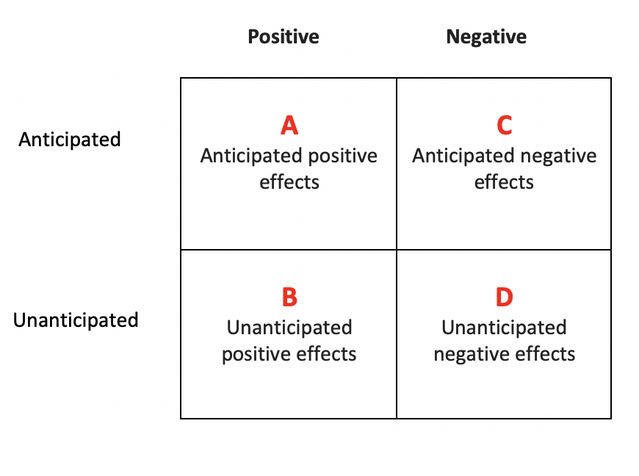

It is well known that social interventions often carry with them a variety of unintended consequences, some positive (“collateral benefits”) and some harmful. R.K. Merton wrote about this in back in 1936, in his paper “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action.” More recently, in a meeting I attended in New York, Paul Bolton of Johns Hopkins University captured this idea in a wonderfully simple two-by-two matrix:

Cell A is whatever we aim to achieve with our intervention. In Cell B are the unexpected collateral benefits that result from the program. For example, a group intervention aimed at increasing parenting knowledge and skill among new parents may have the unplanned benefit of increasing social support among group members, leading to lowered stress and improved mental health (both of which happen to lead to better parenting). Cell C includes those negative effects we expect might occur, and for which we can develop preventive strategies. For example, anesthesia often causes nausea when people awaken; therefore, physicians will sometimes give patients anti-emetic drugs prior to their awakening to prevent this unpleasant side effect. Cell D is the great challenge: It includes all the harms that may occur, but which we don’t foresee prior to implementation. For example, an HIV prevention program for African-American women in the United States initially encouraged participants to insist that their partners use condoms; however, many men interpreted this as an expression of distrust and found it offensive. Some men even became violent. As a result, this preventive intervention actually increased the occurrence of violence against several of the women in the study.

When we are developing an intervention, ideally we have the time to anticipate what the possible adverse consequences might be, and put in place strategies to mitigate or prevent those unwanted effects. That is, we try to minimize the effects in Cell D, by shifting them to Cell C, so that we can either modify our intervention or plan ways of minimizing any adverse effects. To not do so, when we have the luxury of time on our side, is a risky strategy that can backfire painfully.

Sometimes, however, we simply don’t have the luxury of time to plan ahead. This moment in history is precisely such a a time.

The world is in the midst of a pandemic caused by the wildfire spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by a novel coronavirus. Most public health experts agree that the best strategy for slowing, and eventually stopping, the spread of the virus is social distancing, or physical distancing, as some (myself included) suggest calling it to underscore the importance of maintaining physical distance while preserving social connections. There are some experts who hold a different view, and there are examples of countries that have eschewed widespread physical distancing, opting instead for comprehensive testing of their population and isolation of sick or high-risk individuals to successfully slow the virus. Nonetheless, the overall consensus is that physical distancing is the key to stopping the virus, coupled with various preventive strategies such as frequent hand washing, not touching one’s face, and, more recently, wearing face masks in public.

I don’t question the wisdom of physical distancing. On the contrary, I nod to the expertise of the many physicians and epidemiologists who strongly advocate it.

My purpose here is simply to draw attention to some of the unanticipated negative consequences of this global social intervention and its more extreme expression in the lockdowns now in effect in countries such as Italy, Spain, Lebanon, and Greece. There was precious little time to consider and prepare for the enormous challenges that such distancing and isolation would create, the hardships that would ensue in so many domains of everyday life.

My hope is that greater attention to these challenges, and to harms both real and potential, may lead to strategies for mitigating them so that physical distancing can achieve its public health goal of stopping the virus, with minimal cost to the physical and psychological health of everyone involved.

Part II of this post can be found here.