The long, hot summer is over. It’s time to head out to the country, fire up the grill and kick back. The hardworking men and women of America are taking a day off.

According to the US Department of Labor, Labor Day in America started out with a parade and a picnic at Wendel’s Elm Park in New York. The Central Labor Union had passed a resolution that the 5th of September should be a general holiday for the working people of their city. Close to a dozen years later, on the 28th of June, 1894, Labor Day was set aside as a legal holiday by the United States Congress.

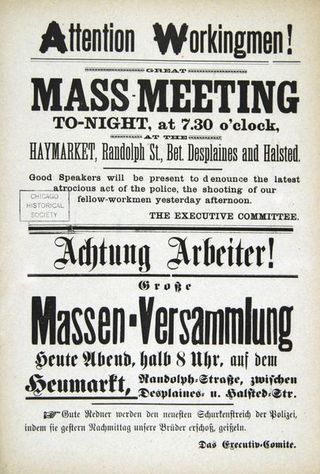

In other parts of the world, they celebrate on May 1st. Just 2 years after the first Labor Day in New York, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions organized a strike in support of the 40 hour week. On Saturday, May 1st of 1886, as many as half a million workers took part in that strike, coast to coast. And on Tuesday, May 4th, there was a riot at Haymarket Square. 7 police officers died when a bomb went off, and 4 anarchists were hung from the gallows outside of Chicago.

In their honor, since the Second International met on the French Revolution centennial, International Workers’ Day has been celebrated worldwide on May 1st—from India to China, from Europe to Latin America, from Israel to Iraq.

Over the long course of history, Labor Days and Workers’ Days are apparently without precedent. The written record, or history, started with civilization, in the first cities of around 5000 years ago. Before the written record, before history, most human societies were fairly egalitarian. After the written record, after history, they were not.

Herodotus, who was known as the father of history, wrote about how the pyramids went up in Egypt. He guessed that the work had gone on in 3 month shifts, with 100,000 men in a shift, over a period of 20 years. Workers hauled stone from quarries in the Arabian hills to the Nile, then fitted the polished stone blocks in steps. “They were compelled without exception to labor as slaves.” There was no record of picnics.

Hundreds of years after Herodotus, China’s first historian, Sima Qian, wrote about how the First Emperor conscripted workers to build another tomb. Over 700,000 condemned castrates and convict laborers were called up, some to work on the emperor’s palace at Shanglin, and the others to carve out his mausoleum at Mt Li. Replicas of palaces and officials, horses and soldiers armed with crossbows were made for that tomb. “Cracking his long whip, he drove the universe before him.” There was no record of parades.

Over the much longer course of natural history, there have been many animal societies. And most—whether made up of insects, or birds, or mammals, or fish—have been filled with what biologists call “workers,” or “helpers-at-the-nest.” Most helpers or workers devoted their days to hard labor: they fetched food and prepared it; they built and cleaned house; they defended their homes from invaders; and they babysat. While most of the insect, bird, mammal or fish bosses they worked for, or helped, did less: they ate, rested, cowered under cover, and reproduced. So when given a chance, most workers and helpers run off. Superb fairywrens are dull brown or iridescent blue birds that nest in the shrubs, gardens and grasslands around Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra. Dull brown males, the nonbreeders, tend to be “helpers-at-the-nest:” they defend territories against currawongs and kookaburra, red foxes and black rats; and they feed the young that iridescent breeders produce. But when given an opportunity, the dull brown nonbreeders fly off. When Steve Pruett-Jones and his colleagues removed breeding males from their nests, they found that nonbreeding males filled those vacancies in 31 out of 32 cases. It took them an average of about 5 hours. And afterwards, their plumage turned blue.

The history of Labor Day, and the history of the Labor Movement, starts with the mass migrations from Europe that followed Columbus, that spurred trade, industry, enlightenment, and representative government. Equal opportunity—in history, as in natural history—begins with freedom to move. And for most us, that freedom is remarkably new.

So have a cold beer, go for a swim, and enjoy your day off. You’ve earned it. Generations of helpers-at-the-nest and workers have earned it, too—more than most of us bother to count.

SOUNDTRACK: