Relationships

When Parents Offer Gaslighting Instead of Love

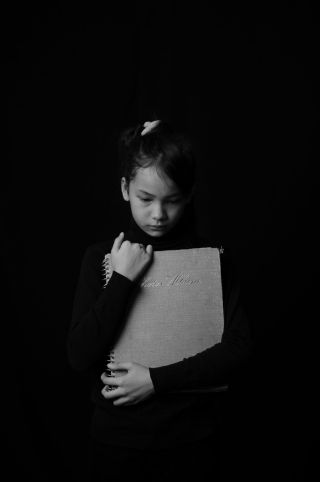

Childhoods to be survived, not savored.

Posted April 14, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Some kinds of bad parenting are invisible to outsiders. A bit like white-collar crime, they are hidden behind perfectly acceptable appearances. They involve no physical abuse or child neglect. They are compatible with taking children to the museum, checking on their progress in school, and organizing birthday parties. They are subtler and more insidious.

Consider a passage from Augusten Burroughs' autobiographical A Wolf at the Table, about his own relationship with his father:

I thought of the few times we'd gone to the university together and how he'd taken me around and introduced me to his colleagues. He'd seemed like such a dad that I'd wondered what was wrong with me to always feel so suspicious of him. I remember thinking how in the light of day out in the world, my father was just like anybody's father. But as soon as I was alone with him, Dad was gone and dead was there in his place.

Riding back from the grocery store, I realized my father was two men—one he presented to the outside world, and one, far darker, that was always there, behind the face everybody saw. [1]

The father Burroughs describes is extremely aloof and distant and never engages in a joint activity with his son despite the child's desperate attempts to gain his father's affection. Elsewhere in the book, Burroughs writes:

As a little boy, I had a dream that my father had taken me to the woods where there was a dead body. He buried it and told me I must never tell. It was the only thing we'd ever done together as father and son, and I promised not to tell. But unlike most dreams, the memory of this one never left me. And sometimes I wasn't altogether sure about one thing: Was it just a dream? [2]

Parental two-facedness is only one form psychological abuse can take. There are others.

A mother may accuse her daughter of stealing the father’s love or else condemn her son for loving a girl more than he loves his mother, where the intention is clearly to have the boy compensate for the love the mother needs from the father.

Mothers and fathers sometimes pit children against each other; they may play favorites but persuade the unloved child it's all his or her fault for not being more gifted, prettier, and otherwise more lovable. (Psychiatrist Irvin Yalom tells a chilling story of a woman whose young daughter died and who realized in the course of therapy that she was blaming her son for not being the one to have died instead of her daughter.) [3]

Blame is particularly pernicious. The problem is not simply that the parent is accusing the child of what is not the child's fault. That's bad but need not be harmful.

Say a parent comes back from work angry and flies into a rage seemingly for no reason. Children feel intuitively, even at a very early age, that this is a heat of passion moment. The parent was like a seething volcano, ready to erupt, and not surprisingly, lost it.

That's the kind of storm a child can learn to weather (unless, perhaps, it happens too frequently). Moreover, a good parent, in such a case, is likely to feel guilty afterward and try to compensate children for unfairly directing anger at them. The damage here can be contained. The tumor on the bond between parent and child can be removed because it hasn't spread, permeating every fiber of the connection between the two.

Not so with cases in which parents blame children for their own marital or life unhappiness. There, the parent involves a child in a poisoned web of attitudes. The whole system of interaction is toxic. This is cancer that has metastasized. There is no storm to wait out. One must wait out one's whole childhood, and even then, it won't be over.

It is important to note that the spread of this type of toxicity can take place using very few words. Several remarks made over the course of a few years may suffice. The infected system of relationships may co-exist with a deceptive, picture-perfect family image, as in Augusten Burroughs' case above. The child affected by what remains hidden from view may not realize until very much later just what was going on. That's to be expected. It is difficult for any of us to believe that we really saw what no one else did.

It may take many years to acknowledge to ourselves that we have been victims of parental abuse. There are several reasons for this.

First, the thought of not having been loved by the only people in the world who were supposed to love and support us come what may is a humiliating thought, and we naturally look for ways to avoid the pain of humiliation even at the cost of suffering other kinds of pain.

Second, we can simply carry the distorted beliefs our parents may have instilled in us without examining them. If mothers and fathers made us believe we weren't favored because our brothers or sisters were much better, we may not consider how unjust to us that was until much later in life.

Last but not least, strangers often refuse to believe victims of parental abuse, choosing instead to hold on to what in another post I describe as the no bad parent myth, roughly, the idea that there are bad and ungrateful children but not bad and abusive parents.

When the abusive parents are deceased by the time the fog clears and we perceive the truth about our childhoods, it may be even more difficult. Anger at a dead parent is often experienced as unacceptable and so gets denied and suppressed.

Finally, delayed anger, unlike rage, can persist for years. The good thing about rage is that it is a very intense state and so bound to peak and subside shortly after. Delayed anger that simmers quietly under the surface, by contrast, can torment us for a very long time.

Gaslighted and otherwise psychologically abused children often show remarkable resilience and go on to become good and successful people, despite the toxins left by parents in their psyches. Some intuitively stumble upon the technique of distraction and refocusing, and pour their energy into various pursuits. But this does not mean that they have healed. What it means, rather, is that resilient people can go on despite trauma, like soldiers who continue marching in battle in spite of injury.

What else can be done? For the children of psychologically abusive parents, probably not much, unfortunately. (There is therapy, of course, but who would take the abusive parents' children to the therapist?)

For adults, accepting the truth of what happened, I think, is the crucial part. It is only the beginning, but without it, the rest will never come. To attempt to heal from childhood trauma while denying its cause is a bit like trying to recover from a physical illness after misdiagnosing it and taking the wrong remedy.

Try as you may, you probably won't succeed in finally getting your mother's love by becoming more successful than your brother, whom she always preferred. It may simply be that you will never get her love by any means. If she is deceased, you may not be able to confront her about it either. You must find a way to heal without ever repairing the broken relationship.

But something can be done. The key, I believe, is to fully accept that you were not at fault. A child should not have to win a parent's love nor compete for it as one might compete with a coworker for a promotion. That your parents didn't love you is simply not on you. It's on them.

How much were they at fault? It could be difficult to say. While as the adults in the situation, they should have known better, they may have been enacting a psychological pattern that they did not invent or fully control.

It may also help to remember that if your relationship with your parents was ambivalent, they likely had some affection for you, albeit not the kind of pure well-wishing and love one might hope for. Indeed, a bad parent’s love for a child—which frequently exists alongside bad parenting—is often more personal than that same parent’s toxicity. The gaslighting may have psychological triggers that have nothing to do with you; you are just the victim. Your mother or father became abusers to fulfill a dark psychological need, and there you were, a perfect target. Whatever love they may have felt alongside this, by contrast, was for you.

I am by no means suggesting that grown children ought to forgive their parents. While true forgiveness is therapeutic, and we do sometimes, upon reflecting on abusive parents' circumstances, discover reasons to take pity on them and to forgive, adult sons and daughters may or may not have it in them to forgive. Neither is forgiveness ever owed by victims to abusers, whatever the abusers' circumstances.

In her novel The Judge, Rebecca West writes, “Every mother is a judge who sentences her children for the sins of the father.” Perhaps we can add that, eventually, every child becomes a judge too, one who sentences his or her parents for their own sins.

Follow me here.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: fizkes/Shutterstock

References

[1] Burroughs, A. (2008). A Wolf at the Table. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Yalom, I. (2012). Love’s Executioner & Other Takes of Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books.