Relationships

"It's Your Fault, Not Mine!"

Blame and shame have the potential to wreak havoc on our relationships.

Posted February 11, 2020 Reviewed by Daniel Lyons M.A.

Growing up, fights with my little brother followed a predictable tango-like sequence. First, he’d barge into my room. Next, he’d find some way to antagonize me – touch my stuff, fart, poke me, make kissy noises that drove me crazy. I’d scream to get out. And when he refused, I’d chase him into his room, wailing like a banshee. Sometimes I may have slapped or pushed. Inevitably, he’d yell, “Mom, Kim hit me” or, “Mom, Kim’s bothering me.”

You can probably guess what I yelled back. “It’s not my fault!”

Mom tried to be fair. But more often than not, I got scolded. I was the older sister. I should know better. Of course, that made me feel bad and confused. I mean, he started it… didn’t he?

Today, I view my brother’s behavior through a more benevolent lens. He was probably just looking to play with me. And when I blew him off because I was absorbed in my oh-so-important Barbie fashion show, he found a clever and effective way to get my attention. So maybe it was kind of my fault.

Furthermore, my angry and violent reactions were not OK. So even if I had unwittingly hurt him by ignoring him, and had been innocently playing with my dolls when he got obnoxious, I became complicit in the problem through my response.

This confusion about fault followed me into adulthood, often keeping me up at night. For years, whenever I had an interpersonal conflict, my gut defense was defensiveness, “it’s not my fault.” Of course, this fleeting thought generally gave way to the belief that everything was my fault, which left me feeling unnecessarily guilty.

It’s only through maturity and growing self-confidence that I’ve had the ability to more accurately discern my role in conflict from other people’s. But still, defensiveness can trip me up sometimes.

Who’s Fault is It?

As a psychotherapist, I see I’m not alone in my confusion. If I had to guess, I’d say roughly 75 percent of my sessions are focused on helping people parse their roles in interpersonal conflicts.

I see individuals who tend to err on the side of feeling, like me, guilty about everything, even if a part of them doesn’t think they’re responsible. They can be overly apologetic, berate themselves unnecessarily, and believe what other people say about them without filtered reflection.

On the flip side, there are the perpetual victims, who seek empathy and validation because nothing is ever their fault. This stance is problematic because it’s impossible. We’re human, therefore we err.

Regardless, both extremes are unconstructive because chances are, if you’re in an interpersonal conflict, you probably did something. But maybe it wasn’t something necessarily “wrong.” Either way, the story you tell yourself about the problem, the feelings it brings up, how you respond, and how it affects your relationship with yourself and the other person is very important, and not so cut and dry. Meanwhile, blaming and shaming can be detrimental to relationships, preventing us from engaging in productive soul searching.

The Blame Game

To untangle the fault knot, let’s first address why we blame.

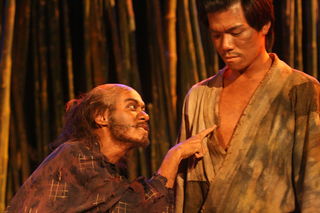

Blaming is as old as history itself, as portrayed in our earliest historical, mythical and literary narratives. Ever since Adam blamed the apple-offering Eve, who pointed at the snake, humans have been passing the buck. Some famous scapegoats in history include the mythical Pandora, Joan of Arc, Julius Caesar, the Salem Witches, Leon Trotsky, Patient Zero in the AIDS epidemic, and, more recently, The Whistleblower. Blaming is also at the heart of racism, anti-Semitism, and other forms of persecution.

The truth is we’re conditioned to find fault for good reasons. We live in a society where people step on each other’s toes. Sometimes a simple apology will suffice, especially when it’s an accident. But what if someone breaks your toe because they were texting instead of watching where they were going? If you’re a dancer, now you’ve got medical bills and you can’t work for at least a month. Or far worse, what if someone purposely breaks your toe because they were mad at you, or don’t like the color of your skin? Without fault, there would be no consequences, and without consequences, there would be lawlessness.

We also blame for psychologically self-protective reasons, for example:

- We equate being wrong with being bad, unlovable, or unworthy

- We project our own fears and insecurities onto other people

- We lose touch with — or don’t know how to express our softer emotions – sadness, shame, fear – in the midst of an argument

- We’ve been taught to blame and know no other way

- We don’t want to risk being vulnerable

- We don’t want to take responsibility

- We don’t want to change; and

- We feel anxious living in an imperfect world we can’t control

Simply put, it feels better than guilt. If you’re not at fault, you didn’t make a mistake. And if you didn’t make a mistake, you’re not bad. And if you’re not bad, you don’t need to change, which can be scary and difficult. But if you don’t need to change, the other person does! So you’re off the hook.

It takes a pretty strong ego to hold the dualistic notion that we can be ostensibly “good” people, who occasionally screw up, sometimes in epic ways. Some of us grew up with stories about what it means to do something wrong. Parents who screamed at us when we accidentally spilled milk, or who blamed and shamed us for crying when we were being neglected may leave us with subconscious messages about ourselves – that we are bad, unlovable, or worthless. These messages, if relayed over and over again, can codify into entrenched beliefs about ourselves that have more to do with our parents’ reactions than with who were are at our core.

We may not be aware of these messages. In fact, we may feel like a confident lawyer, parent, artist or business person. But the second something happens that awakens the deep, dark feelings, of our inner “unloveable child,” it can be too much to bear.

“It’s not my fault,” gets us off the hook and redeems our worth.

Do True Victims Exist?

That said, there are such things as legitimate victims – especially when it comes to child abuse, rape, murder, ethnic persecution, slavery, genocide, and other criminal, inhumane acts.

Even in the realm of everyday interpersonal conflicts, sometimes things are genuinely not our fault – they are other people’s projections, which can be harmful for us to internalize. In this case, respectfully asserting our truth becomes an essential part of our growth. Furthermore, there is nothing worse than being falsely accused. My heart breaks every time I read about convicts being exonerated for crimes due to DNA evidence after serving years in prison. I can barely stand a few days when someone misunderstands a text, and jumps to false conclusions about my intentions. Serving years for a murder I didn’t commit seems existentially cruel and unfathomable.

Still, there is hope. If we can untangle the fault knot, we can take responsibility for our own experience, mistakes or assumptions without taking on other people’s baggage. That way, we can avoid fault traps altogether, and navigate disagreements with more satisfying outcomes.