Persuasion

What Turns Some People Into Hoarders

Brain lesion patients provide new insights about hoarding.

Posted November 24, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

In reading my recent book, Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play, a professor pointed out to me that she realized for the first time that hoarding could be due to organicity rather than psychological factors. She emphasized to me that this concept is a novel idea to most students of collecting and/or hoarders, and it's an area that needs more attention. The professor was right, and she spurred me to action.

Putting the Issue in Perspective

Although one-third of the American population, roughly 197 million people, collect one thing or another. Many fewer are hoarders, between 6 and 15 million. Still, this group garners the most publicity. The underlying cause of their affliction is thought to be variable. In one large U.S. study, major depressive disorder was found in over 50 percent of hoarders. Generalized anxiety and social phobia were uncovered in roughly 25 percent. Fewer than 20 percent had obsessive-compulsive disorder.

More Complicated Than It Seems

Still, there is likely more here than meets the eye. Researchers at the University of Iowa examined 86 patients with brain lesions. Thirteen displayed new abnormal collecting behavior that was severe and associated with troublesome accumulation of useless objects.

They exhibited this behavior only after the onset of their lesions, not before. A close relative, usually a spouse was the source of this information. To qualify as a hoarder, the individual had to accumulate objects of little value to excess in such a way that their collecting interfered with daily function. For example, “A 70-year-old, right-handed, retired (female) bank clerk with 13 years of education underwent resection of an orbitofrontal meningioma (a tumor, usually benign). Her husband noted that she had been reluctant to throw away items with potential value all of her life, but that this characteristic was not so prominent as to cause any problems. However, following surgery, she began to collect large quantities of a wide array of items to the extent that serious space problems arose in their home. Most were mail-order, particularly clothes, which her husband would intercept and return.”

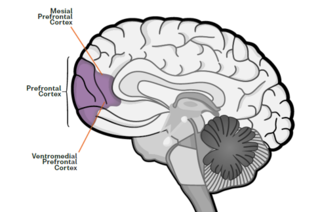

When the brain lesion patients who collected excessively were compared to those who did not, they did not differ in age or standardized neuropsychological tests designed to determine intellectual abilities. Additionally, the two groups were alike when examined for executive function skills and anterograde memory (which is the ability to recall events in the distant past but not recent occurrences). The difference was that the collecting group had damage in a specific part of the frontal lobe called the mesial (defined as the middle) prefrontal cortex.

The noncollecting group did not. It is worth noting that the same area is activated by fMRI when we perceive beauty. These two observations, taken together, support my belief that there is still a great deal to learn about the intersection of the appreciation of beauty and collecting.

The authors postulated that in people without brain damage, deep limbic brain structures initiate the drive to collect. It then is modulated by a prefrontal neural system including mesial sectors. Without the tempering influence from the frontal mesial area, collecting behavior can go awry. The authors interpreted the presence of this specific lesion in those who collected excessively to mean that a normal overriding inhibitory system was disrupted. Without its influence, the drive to collect objects was free to operate without its usual restraints. This resulted in disinhibition which, in turn, led to collecting gone awry. I postulate that the reverse could also be true. The mesial sector is more active, and objects not previously found to be attractive become so.

Promise for a New and Better Understanding

Today, as neurology and psychiatry are beginning to merge, few would say that collecting is pathological. But, perhaps as hoarding is investigated in years to come, detection of an organic basis for at least some cases may lead us to a better understanding not only of hoarding, but the drive that motivates collectors as well.

This post was adapted from chapter six of the book Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: trekandshoot/Shutterstock