Sleep

Sleep: The Clean-Up Crew of a Dirty Mind

Sleep isn't a passive state, but an active one that literally clears your head.

Posted February 19, 2014

Updated: May 30, 2020

When you throw a party, you don’t clean up until everyone’s gone home. The brain parties every moment you are awake.

The waking brain makes a mess

While it’s alert and it makes a mess, just like partiers everywhere do. All living cells metabolize energy. And as they burn fuel they leave behind residue and toxic wastes—the equivalent of empty glasses, smelly ashtrays, and dirty dishes that hosts confront when the action is over and things have died down.

To tidy the place up a host must exert energy to reverse the disarray (its entropy, to use the scientific name for disorder). But how the brain flushes out waste has been a mystery until now. That’s because, unlike every other organ in the body, the brain has no lymphatic channels, the stand-alone drainage highway that transports white blood cells, antigens, and metabolic waste from our organs to the lymph nodes.

Filtering out toxins during sleep

In humans, 700 such lymph nodes filter the extracellular liquid before returning it to the circulatory system by way of the large subclavian veins in the neck (they lie next to the jugular). Blood circulates in a loop, but lymph flows only in one direction towards the heart. Other parts of the lymphatic system include the tonsils, adenoids, spleen, and thymus.

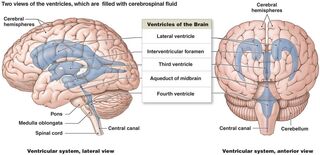

Just how does the brain get around the shortcoming of having no lymphatics? One answer, published in the journal Science, may lie in the cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF. This crystal clear fluid is constantly secreted into the central nervous system and reabsorbed. CSF is manufactured inside the hollow ventricles. The fluid circulates over the outer brain surface and spinal cord, and then percolates through nervous tissue and bathes the entire “interstitial” space between individual cells. The fluid is reabsorbed into veins, enters the general blood circulation, and the cycle begins anew.

During this unique rinsing cycle it appears that the brain not only flushes away toxic waste but also picks up beneficial molecules and nutrients. At the moment we know most about how it handles waste. And what we do know is pretty surprising because it contradicts what we’ve thought was the case for decades.

Sleep deprivation builds up the concentrations of both beta–amyloid and neural plaques, two hallmark abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease. For decades we have known that demented individuals do not sleep for long or well. Traditionally we have attributed that to the degeneration their brains were undergoing. But researchers have begun to question whether insomnia might actually be a cause of mental decline rather than its result.

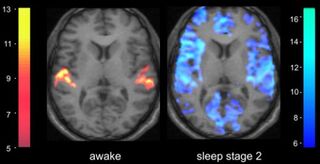

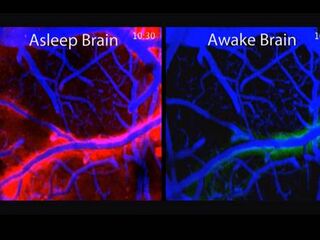

In mice, where direct observation of brain tissue is possible, CSF dyed with a visible marker circulates briskly when animals are either anesthetized or naturally asleep, but not when they are awake. Toxins, including beta-amyloid, are flushed away twice as rapidly in sleeping brains than in wakeful ones.

A follow-on study in humans confirmed the finding by recording rising levels of beta-amyloid during wakefulness and falling ones during sleep. The pattern is particularly robust in teenagers and young adults. So mothers, as usual, are right: young people need their sleep if they want to be mentally sharp the next day.

What the long-term effects of sleep deprivation are with respect to dementia are not yet clear. For now it remains a chicken-and-egg question. But it’s something you may want to sleep on.

Send comments to neuroman@gwu.edu at the links below, or to ask for a free copy of "Your Brain on Screens.