Why is it that we get sad when we see someone crying and wince when a friend cuts his finger? Do animals feel this emotional contagion as we do? An experiment published today in the leading journal Current Biology shows how the brain makes us share the emotions of others and how similarly the brain of humans and rats seem when sharing emotions (see Carrillo et al, 2019).

For a long time, people believed that empathy is a uniquely human sentiment that sets us apart as a more moral species. More recent observations chip away at this notion. Dramatic anecdotes surfaced of chimpanzees who risked drowning in heroic attempts to rescue fellow chimpanzees in aquatic peril. Studies showed rats, not known as the noblest of moral beings, invest considerable effort to free fellow rats from a trap (see Do Rats Have Compassion?). Indeed, emotions are contagious among rats: If one receives a mild, but startling electrical shock, it gets scared and freezes; it stops all movements. Rats do so to avoid being detected by the main danger they encounter: predators. What is fascinating is that rats that witness the fear of another rat have been observed also to freeze. Somehow, the fear of one rat is transferred to other, nearby rats, just as we get nervous around nervous people. This observation paved the way to looking into the brains of humans and rats to see what mechanisms make emotions travel from one individual to another, and to understand whether these mechanisms are similar across species.

In humans, this has been done using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and typical experiments involve two conditions: one in which the participant is exposed to a stimulus that triggers an emotion, and one in which the participant witnesses someone else experience that emotion.

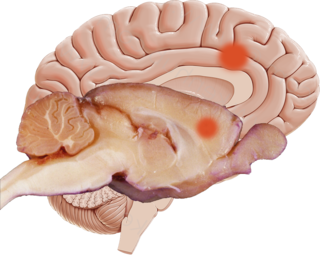

For instance, we can apply a mild electroshock to the hand of a participant to see what brain regions are involved in feeling pain. The core brain region that activates is the anterior cingulate cortex. People with damage in this region no longer feel the emotional agony we associate with pain, and this region is thus thought to be the hub of our emotional pain.

Interestingly, if you let the participant witness someone else get such a shock, participants activate brain regions involved in vision, but in addition, they also activate their cingulate cortex, as if they were suffering themselves. That the same brain region is involved in pain and in witnessing the pain of others led to the speculation that it may contain pain mirror neurons—nerve cells that map the pain of others onto our own sense of pain. Pain mirror neurons remained theoretical speculation, a kind of Higgs boson of emotional empathy—much speculated about but unobserved.

By recording from individual neurons in the same brain regions of rats, the existence of pain mirror neurons has now been confirmed. In the rat cingulate cortex, many neurons responded when the rat felt pain itself but not when it was only scared by a tone. These neurons thus seem to be tightly linked to the animal’s own sense of pain. The majority of these pain neurons, however, also responded when the rat witnessed another rat in pain, and did so within less than a tenth of a second. Just like the speculations on pain mirror neurons had predicted, the rat’s cingulate cortex thus contains nerve cells that translate the witnessed pain of another into the substrate of the observer’s own sufferance.

That the rodent’s own pain neurons got recruited so swiftly is telling in that it makes the sharing of pain more akin to a quick reflex rather than to a deliberate, reflective act of mental perspective taking. That this occurs in the cingulate cortex, the very place in which humans activate their brain while they witness the pain of others, shows that rats and humans seem to share the basic biology of emotion sharing. We do not only share the ability to take part in the agony of others with rodents: We do so using the same brain systems, the same fruits of social evolution. Empathy has routes that run deep in the tree of evolution and connect us with our fellow mammals.

You may wonder: How do we know that these neurons really do make us share the pain of others? To answer that question, the activity of the cingulate cortex was suppressed by injecting a drug into the very brain region where the pain mirror neurons were found. Now the rats that observed the distress of others no longer showed signs of sharing that distress. Altering activity in the cingulate sufficed to alter emotion sharing.

Psychopathic criminals do terrible things to people without feeling the moral shackles of remorse and empathy. Intriguingly, just as the rats with pharmacologically suppressed cingulate activity, such psychopaths show reduced activity in their own pain regions while witnessing the pain of others (see Inside the mind of a psychopath). An animal model in which emotion sharing can be altered offers hope for unlocking the development of drugs to normalize empathy in patients who suffer from abnormal empathy.

Although it remains difficult to really know what animals feel, the similarity across species in the brain mechanisms that are at play is striking. Perhaps the intuition we have that animals are endowed with empathy is not as irrational as some once thought.

References

Carrillo, M., Han, Y., Migliorati, F., Liu, M., Gazzola, V., and Keysers, C. (2019). Emotional Mirrors in the Rat’s Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Current Biology. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(19)30322-7