I've published a couple of columns on somatics, including an interview with Sumitra Rajkumar, the practitioner I work with--my therapist. Part 2 of that interview is more like a conversation than an interview.

The ethos of somatics is to embody feelings and purpose, so I want to get concrete about how that works. Sumitra and I decided the best way to do this would be through a dialogue comparing our perspectives on the nitty-gritty of the work we do together. We also want to open up the private space of the therapist's office because so much of somatics involves a commitment to social connections and movements, to relationships and the institutions that make our world what it is.

Somatics is also deeply ethical and rooted in consent. I hope this conversation reflects that. Think about Freud’s case histories of his famous patients, like Dora or the Wolf Man. Freud claims all the power to tell the story, and his subjects get reduced to illustrations of his theories. Consent was not a factor for him. What’s therapeutic about that? Instead, Sumitra and I are having a messier but more honest conversation about our work together. I hope it also comes through that this kind of somatic work is about the evolution of both client and practitioner, as individuals who are part of a collective world. So it’s also about tuning our commitments to other people, the larger world—and ultimately to the pursuit of justice and fairness.

JASON

In one of our early sessions, we centered ourselves together. Centering involves breathing, giving your attention to your core, bringing the height, depth, and width of your body into awareness. It involves a kind of inventory of what your body is doing and feeling in the moment.

What I remember next is that you had me pushing you across the room!

I know this isn’t exactly what we were doing. It was much more considered and intentional. But that’s how it felt in the moment. It both excited and freaked me out. I don’t know if I can remember it accurately. I think you taught me a move where you walked toward me, with your palms held up. You asked me to use my palms to push you across the room. You told me to yell “NO!” while doing it. You told me my goal was to move your body using my core, not my hands.

Now, I’m game. It’s one good thing about how I’m shaped (the somatics term for how intimate and social factors in life have conditioned your way of being). But I also have a lot of inhibitions around strong expressions and especially anything resembling violence. One of the commitments I’ve been practicing in somatics is freedom—all kinds, but definitely freedom to make an impact and be comfortable with that. At this early moment, I was pretty afraid of making an impact. I was afraid of hurting you, or even acting out a kind of violence directed at you. It was really a shock for me to do this. You want me to push you across the room? Yep, you said.

SUMITRA

Ha! By the way, I love the “it’s one good thing about how I’m shaped,” Jason. You were indeed totally game! But, there are many incredible things about how you’re shaped, not just one, and may I remind you that you very much enjoy those things about yourself -- just to get a quick scolding in before we begin? Nothing like a good, therapeutic scolding in public, right?

JASON

I love a good public scolding—so long as it’s one imbued with trust and love! I’ll take it. Yes, there are a lot of good things about how I’m shaped, and I savor those. I need reminding sometimes. But I will say, it takes some ego to be a writer. It takes what novelist Siri Hustvedt calls some “adaptive grandiosity.” I am a fan of myself. Let’s face it.

SUMITRA

Adaptive grandiosity as an artist sounds fabulous—a way to celebrate your worth and have the confidence to express your voice without it devolving to narcissism. So glad you found that. I want to embody it too for my own aspirations as a writer.

JASON

But I also have layers of history of inhibition and shame. Some of them come from growing up poor in a capitalist world, some from childhood abuse and trauma, some from being bullied as a gay kid, some from coming of age during the early days of HIV and AIDS. I experienced and witnessed a lot of violence and suffering.

I have since learned the value of pushing through inhibitions to get to something primal that wants to come out and circulate. You explained at the time that if I know I can express and embody this HARD NO—what you call the push away—it will give me a kind of peace. I’ll know I can do it if I need to, and because of that when I say no in more ordinary circumstances, I can do it with more grace or soft edges, more intention about whether I’m saying, “No, but I want to keep working with you on this” or “No way, I’m out of here. I want nothing to do with this,” or “No, but I really love you and I respect that you asked.” There are so many ways to say no, many of them loving or relational. I’m working on having more of them in my repertoire.

I spent the whole week after telling this story to my friends, probably pretty dramatically. It was a big deal to me.

How do you remember that session? I’m guessing your memories are a little different. I bet people would love to hear your take on what this particular somatics practice is all about—one of several fundamental consent practices. What’s your aim when you ask a client to push you across the room?!

SUMITRA

So your readers know what they are getting into, we are going to delve into some painful details about your personal history. You decided you wanted to do this because of how rare it is for a practitioner and client to get to talk openly about specific healing practices in context. Plus you are a seasoned writer and memoirist so we are taking full advantage of your skills for revelation, vulnerability and storytelling—other beautiful ways in which you shaped yourself to survive, by the way. Anyway, since we are about to talk about consent, let’s just practice it live by noting that this was a consensual willing act of open discussion between us, client to practitioner, and vice versa. We also came to a lot of these assessments about you together, through practice, not as a one directional diagnosis.

JASON

100%. This was my idea. I’m glad you consented to collaborate. Writing about an important experience can really help crystallize what it means, in our everyday lives and our ways of thinking about the world. I hope this conversation will also be helpful to others. I hope it will get people curious.

But I still want to hear your take on me pushing you across the room!

SUMITRA

Yes, that push away session was pretty dramatic, wasn’t it? It’s great to read your memory of the push away as a stand out practice in the early days of our work together. It made such an impact in your muscle memory. That makes total sense to me. The push away was the first boundary you had to get skilled at in your commitment to freedom.

Like we talked about in the previous interview, any practice we do fits along your arc of transformation towards what you long to embody. In your case, you had a conviction that you wanted freedom in so many forms-- feelings, actions, relationship, and structures. We always have a verbal mantra or commitment that we declare to ourselves and that we try to find early on in our time together. It can change along the way but becomes the guiding rudder for our work, the point of departure with the destination as its embodiment. It means that, after a given amount of time in practice, we are going to embody this quality and/or purpose much more than we do now including or especially when we’re under pressure, grabbed, or triggered. At least about 80 percent of the time. It’s not just an aspiration; it is a concrete accomplishment. It is not this total finite goal but we are able to measure and assess how it lives in you, how you live it.

The push away made sense in this context of your arc early on. As the practice tends to go, I came towards you with palms facing you and you had your palms ready to meet mine too. As I approached, you pushed me away from your center declaring “NO,” sending me staggering backwards. It was amazing to feel the conviction of your centered boundary, not violent at all, completely consensual, an invitation in fact, and a joy to participate in your learning that skill. The center of your body, the center of gravity was the home base for this push away as it is for many consent-based and other practices. You got to say no with presence as an adult in real time in a core leverage of your physical and emotional power.

The choice of practice was for good reason: What you had shared with me is that you did not get to say no in your early life to the abuse you went through and that you watched your mother go through. Your own boundary was not respected. You also told me that it was not safe to say no even though you certainly did not consent to being violated by adult men in your life. Children are vulnerable and depend on adult guardians for their survival. This was a profound emotional-physical violation that also involved direct verbal assaults on your performance of masculinity. Another person might say no all the time or more aggressively than they may need to, depending on what their bodies adopted to feel safe enough or survive an actual threat. That reaction can stay and replay. You hold back or brace yourself from impacting others including the impact of your own boundaries. The no was not possible and seemed like it could threaten relationships, safety, belonging. This was one of the first things you told me about yourself, remember?

Practicing declines in your muscle memory got you to feel that boundary in your body that you didn’t get to feel or even know you had when you were being traumatized as a vulnerable child. You were stunned because you had an internal story about consent that shifted almost instantly--boundaries can actually enliven and dignify you and even those you are saying no to. We did a whole symphony of centered declines after that! For example, the redirect is a firm and sustained guided no that keeps you clearly on route to your own commitment, the intimate decline is also firm but gently invites you to stay in connection, or there’s the counter offer and also other consent practices like centered requests and offers and also centered yesses and even maybes. All of them got you the core consent-based skills that help you live freedom. You really took to all those physical consent practices as a way to achieve more ease and peace with people in your life, also freeing. Your tissues started to soak them up like they had been waiting for it.

JASON

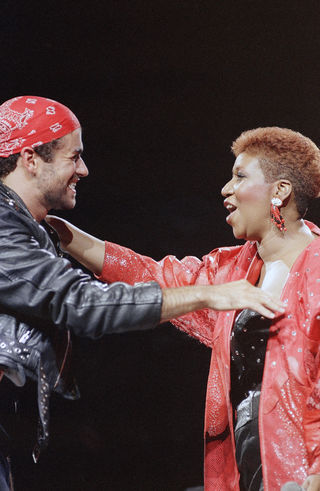

Yes, I remember that when we first met, you asked me to make a commitment to a clear ideal or purpose. I chose freedom. It’s a commitment with many tentacles. It can mean a lot of things, but every move we’ve made since is about freedom in some way--embodying freedom to be me, free of shame, freedom to express myself, freedom to face stress or difficult people with presence and equanimity. Now, it's no coincidence that Aretha Franklin and George Michael both recorded so many songs about freedom. The way their voices soar--that's the kind of freedom I'm after. Let loose. I'm married to a singer, and I witness the depths of emotion that move through his body when his voice soars. It's one of my inspirations.

When I sought you out, I’d done a lot of traditional talk therapy—and couple’s therapy too, with my husband David. I’d mostly made peace with my chaotic childhood, with my father’s heroin addiction, with the violence and abuse I experienced and witnessed. There was something else: My body. In somatics, there are two key terms: conditioned tendency and safety shape. How is your body conditioned to respond to various stimuli, to stress or triggers or stuff that scares you? What shape does your body take when you’re not feeling safe?

When I would get a haircut or a massage, the person cutting or massaging would of course move my body in various ways. But if you’d tried to move my head just a little, I’d freeze, at a muscular level. If I realized I was doing it, I’d overcompensate by moving my head myself in the way I thought the person wanted me to. I couldn’t let another person move my body. Imagine the implications for my sex life! This was a sign to me that my body remembered the abuse at the level of muscle memory and in my nervous system. I was tired of it. One of my other conditioned tendencies is to zone out—disassociate—when I’m confronted with something that scares me. I’ve tended to do this when faced with authority figures or people who represent upper or middle-class values or habits that intimidate me. I grew up poor, and I’m a professor, working in a world with lots of rules and some elitism. When I felt like I didn’t fit, I’d disassociate.

On top of all that, you helped me acknowledge that I was wounded, in a real, physical-emotional way. You asked me to envision the wound. I got an immediate image of a sea anemome. It could mutate on a dime from beautiful and searching to shameful and disgusting—and then back again. This is sort of a metaphor, but I believe it has a literal life in my body, my muscles, my nerves, my viscera. When I was beaten as a kid, when I watched my mom getting beaten-- that wounded me. I reacted with physical emotion. I spent a lot of time ashamed, covering the wound, but I always knew that it was a source of creativity and power too. The shame was an obstacle to the freedom of the creativity.

SUMITRA

You have an emotional body. We all do: the limbic space that governs our reactions, and where history is often buried in its neuromuscular network. It makes sense that some therapeutic work did bring you emotional peace and then the body went, hold up, I remember, wait a minute–don’t touch me. That smoke alarm goes off in you even though you know it’s just a haircut. That’s the threshold of the real and the surreal, the liminal space that trauma can put us into. You also suggest at this zone of creative wonder that can open up. I wish more research focused on the link between trauma and creativity. I certainly don’t think we need trauma to be creative and I hope that ceases to be any sort of link for all our sakes but there is some wild mystery that trauma seems to set off in certain bodies.

Your beautiful monstrous sea anemone offers that possibility. A wound that makes you suffer but that you have described as wondrous in a way. It is yours. It is an entryway to the very freedom you seek, as though it is your own secret sea garden path to an epic release. It speaks to how we are all resilient beings. We can bounce back from suffering with a deeper desire to live, relate to beauty and connect to the lives of others. Perhaps painful experiences can sometimes stimulate the ability to imagine and create and wonder how more life might be possible.

We always want to build off of the resilience you come with in somatics. And an early chunk of work is also about getting to know your conditioned tendency and also the survival strategies or safety shapes within them. The awareness of this “shaping” happens while also cultivating the path to bring yourself back to center and embodying purpose, or ideal, as you put it.

JASON

I’d love for you to explain a couple of technical concepts—conditioned tendencies and safety shape. You and I have often had conversations about how the terminology can start to feel like jargon—which can alienate or confuse. But the concepts are so practical and helpful that they outweigh this. I just want people to understand our shared perspective on that.

SUMITRA

Conditioned tendencies (CT) are the dominant ways into which we’ve been conditioned and adapted, from behavioral habits to mood to worldview, and they especially include our automatic reactions under pressure. We come by our tendencies honestly. Generally, we say our bodies are shaped to move towards, away from, or against others in relationship. We also say that humans tend to shape themselves within a range of conditions to find safety, dignity or belonging. I think we’d both say that you are shaped or tend “towards” people, Jason, including under pressure. So much in your life suggests that, from your teaching to the chosen family and the community you have purposefully built around you and that is such a part of queer resilience too. Overall you do all you can to sustain that movement towards relationship, including sometimes erasing your own needs

The safety shape lies inside all this and can inform the CT but is more closely related to what kept you safe in traumatic conditions, what the body’s intuitive strategy of survival was. It’s closer to the bone, a deeper set of contractions or armoring. It’s very related to the fight, flight, freeze, appease, disassociate reactions that are at this point in common parlance--that residual reaction to perceived threat, the muscle memory that got stuck in you that kept you safe once but is less useful to you now and that nevertheless you still might default to like a broken record so that there’s less choice in how you be. This reaction is more intense. Feels like the safest or only option in the moment but can feel like hell after, kicks up shame, makes you feel like you aren’t really yourself, causes anxiety or panic or worry. Some people’s CT’s are more directly linked to their safety shapes than others. We often find more than one reactive tendency in some bodies: even an equal and opposite reaction in certain shapes. Those who go forward hard can collapse backwards hard, for example. I see this in so many community organizers, actually. Our bodies have a strange emotive physics to them. Our emotional maps are not simple. But through practice, we can clarify, sort, simplify, air out and ease up on those contradictory reactions, creating more choice in our responses and perceptions over time.

It was smart for you to freeze and to zone out to be safe. It allowed you to strive towards what you wanted while taking care of your self. It assisted an overall “towards” tendency that kept you in relationship. But it did not always give you all you wanted from relationship, that closeness and vulnerability for example, that ease from the bracing fear of impacting others. It made you suspicious of your own belonging and struggle to feel your own dignity and it’s not always useful anymore, so you want more of your emotional choices back.

JASON

With this in mind, I want to talk about Hand on Heart, one of the most direct and intimate somatics practices. You and I stand, facing each other. We center, which means envisioning and embodying the height, width, and depth of our bodies and doing it with commitment to a purpose. You place your palm on my heart, and I place mine on yours. The point is to be with oneself and also with another person, in mutual connection. It took me a while to get comfortable with this. We’re really close to each other. I have a tendency to turn slightly away from you. I get confused about how much pressure to apply. I worry that maybe my hand is too close to your breast.

You taught me that the easiest thing to do is ask: How’s the pressure? How’s the placement? Then, something powerful happens. We enter into a relational bond, centering each other, supporting each other physically, in ways that are beyond words. You’re steadying me, and I’m steadying you. In the process, I’m embodying freedom, eschewing the inhibitions of my safety shape, which can keep me from connecting with other people. As you’ve often said, that shape saved my life in all kinds of ways. But I have other choices now. Hand on heart encapsulates that for me.

SUMITRA

The practice of Mutual Connection, also known as Hand on Heart, is quintessential here. I love how you explain your own practice within it: from the neurosis of intimacy to communication and consent to settling in and tolerating it to the relaxed power and joy of connection. That has taken some practice! It got you to reduce the neurotic tick around emotional intimacy, communication and belonging through basic communication, verbal and nonverbal, and also by just by tolerating being with another while being with yourself. Consent gets worked out through simple questions and affirmations (Contact okay? Chest or shoulder okay? Placement and pressure okay?) and then the practice is just about being present with yourself and with another.

It is jarring for most of us when we first do it because it’s so damn close and involves eye contact and hand contact near our hearts and chest and breast and we can be either all up in the other person or all up in ourselves, depending on your conditioned tendencies, toggling wildly, grabbed or triggered. But, it can become hugely reassuring when we practice tolerating what gets kicked up in the move and find that we are not only safe within it but we’re facing one another with vulnerability and literal heart to heart kindness while taking care of ourselves as well.

Once you felt safe, you could feel the mutual dignity and mutual belonging that was possible and it had relevance for many of your interactions. You could be close to someone without worrying that you or they were doing damage. Even if you had collected evidence of damage from your history.

The practice of “Push way” is an embodiment of a “Centered No” and Mutual Connection is in many ways an embodiment of a “Centered Yes.” It enters us quite boldly and openly into relationship with one another. It is a somatics fundamental and favorite for sure. It can be especially relevant to us politically where we’re building authentic relationship, power and culture with one another in order to face and counteract oppositional and oppressive structures, cultures and worldviews. Mutual connection allows us to see and listen to each other and allow for one another’s dignity and belonging and resilience.

In many ways you’ve already found the resilient, freeing way out by embodying the irreverent teller of tales that you are. You get to air out your own working class and queer rebelliousness and also be the loving, rigorous teacher and supportive colleague who is freed up to take the institution’s rules less seriously. You are deepening into these through boundaries and mutual connection, especially when triggers take you away from yourself and what you value.

Affirming the vast extent of your resilience is important here I think. Your grandmother comes to mind too as the loving, consistent and dignified guide and guardian in your story that helped you reconcile your own striving for class mobility with the internalized class shame and self-critique. She helped feed the possibility in you for more ease and freedom in everyday connection, without overthinking, shutting down or checking out.

JASON

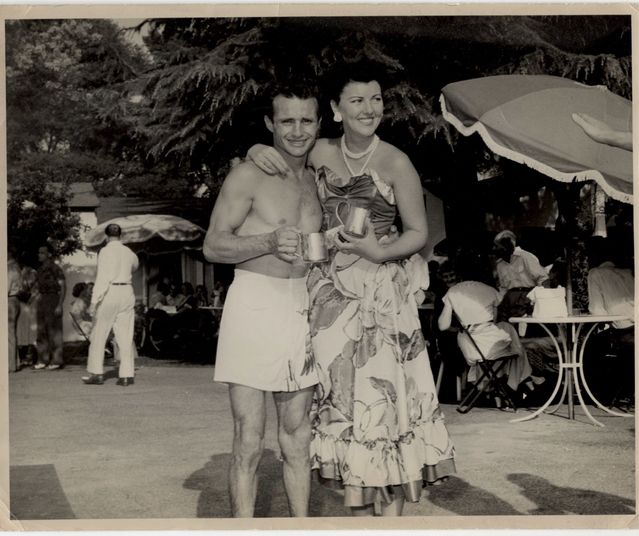

I’m so glad you brought up Nanny—my grandma. She was a savior for me as a kid. She’d flown high in life and had a hard landing, from wealth and celebrity into poverty. My grandpa, Ralph Neves, was a famous jockey. They were loaded. Their best friends were Harry James and Betty Grable. Their neighbors were Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. They divorced right before I was born, the money already vanishing. They lived their last years in separate mobile homes in the same park.

Everybody—and I mean everybody—loved Nanny, known to most as Midge. She was poised, elegant, and supremely wry. We spent a lot of time together. I lived with her when things got bad at home. I learned her wry humor. I learned her fierce determination and her aspirational take on life, even when she was drying paper towels on the laundry line for re-use because we couldn’t afford to buy more. She and I were deeply connected, bits of her in me and bits of me in her.

But Nanny wasn’t perfect. She had a lot of fear, and she hid most of it. Nanny was good at empathizing, but she was terrified of other people seeing her shame and vulnerability. She died of a brain tumor. She kept the symptoms a secret until they were so severe they were evident to all of us. I inherited her fear, especially around stuff about the body, health, and safety. It's my strong belief that a lot of this is physical, beyond cognition. It requires physical practices and their emotional corollaries to dig into it.

SUMITRA

Midge is such an embodiment of dignified glamour! I can just see her wisecracking in that picture with her cocktail--what is it, a mint julep?--arm flung with loving ease around your grandfather. I love how you describe her and how you both have or even are bits of one another. It’s heartwarming and heartbreaking. We are who we come from.

There is also so much to say about her fall from class security and even celebrity in this society and the kind of shame and the ensuing guard and mistrust that sudden poverty can cause. And of course there’s more: all that stoicism and striving, Jason, in her and in you, all that fear of people seeing the wound and taking advantage of it or pitying it. Such good reason to put the guard up. Then there’s also the huge store of resilience that she enabled you with! You have different choices now than in the world your beautiful Nanny had to navigate. It is possible to trust again, to be vulnerable, to be close to those you love, to even choose your own political contributions based on your queer and class experience.

JASON

Somatics can be like dancing. I’m dyslexic, and I have some trouble with spatial relations. Sometimes it takes me a minute to get the moves. I screw it up. We try again. We often end up laughing pretty hard, which is something I really appreciate about our practice. I’ve had therapists say things like, “Is laughter a form of deflection for you?” I object! When we laugh, it’s a form or connection and release. It’s organic to the practice. It injects a little irreverence. Imagine somebody peering in on us form outside. “What are they DOING?” We look pretty funny sometimes.

Now, let me take myself down a notch. I’ve learned not to think of whether I’m embodying my ideals as right or wrong. That’s the easiest way to get up in my head and start wobbling off center. But I do better sometimes than others. Just today I yelled at a colleague by email. I was genuinely angry, and it had been building for a while. So it was honest. But it was also like I wanted to assert my freedom, to yell a hard NO! I don’t think this colleague deserved to be my practice target. That said, life is messy. We screw up, and we impact each other when we do. I don’t really know how I made her feel. Maybe one day I will. But I can imagine other, more compassionate ways of expressing my anger, ways that preserve the relationship rather than threaten to cut it off.

SUMITRA

Laughter is amazing. I believe it’s often a resilient force. But, laughter can also be an urgent and pre-emptive discharge of emotional discomfort, which is hard to tolerate for some people so it makes sense that therapists ask that sometimes. But that’s not always the case. It depends on the shape. Some people laugh nervously all the time and that can be part of their conditioned tendency so it’s important to just pay attention and listen to what the body longs for, different in every case.

In your case I think it’s freeing and connecting for you and it loosens and eases you up. And what can I say Jason, you bring it out of me. It’s also a way that you and I connect because we both see the humor in things, and like to not take ourselves too seriously, especially because I think we can also be very serious, so it’s a good counterbalancing force. Laughter has been a resilient force for both of us in our own lives. As a practitioner I am intentional about yes, “being myself” and infusing organic humor because I do laugh easily but also to not impose it on my clients so I can listen to what they are coming with around it.

We’ve come to a place in somatics where we try to not take the actual techniques too seriously and focus on the principle of the moves instead and how they fit with certain bodies. Yeah we can look weird when we do them: I think it’s good to have that perspective. I remember when a friend came to pick me up from a somatics course and saw us through the window all whirling around and was like, “What the fuck were you doing in there?” I mean we totally can look strange out of certain cultural contexts, hey. But when we do the Jo Kata— we can also look like badass warriors.

In the physical movement techniques, which we can do seated or standing, we often adapt martial arts Aikido moves and principles into relational emotional moves. Works well for social justice principles too. We have been developing healing ways of relating from the practices of warriors, no less! Emotions can feel like a battle, and so can the fight for justice. Approaching from a center of gravity in our bodies can shift how we receive and engage one another’s intentions and actions. But it’s the principle that matters not as much whether your foot is placed correctly or even whether you have a foot. We want to appreciate and move from the physical capacities of a range of bodies and abilities. So, of course we move with your dyslexia and the particularity of your body’s spatial relations. We are all messy creatures.

Speaking of which, in somatics we also believe in engaging our contradictions not suppressing them. It’s not about perfectionism. Rigor is different from perfectionism. Rigor is about paying attention. This can include an attentive surrender or letting go or easing up, if that’s a practice we are less skilled in. Rigor is about tending to each other better and better as people and as a society and growing our individual and collective capacity. Perfectionism and repression often swallow emotional risk and can be an internalized CT (conditioned tendency) of a repressive, bourgeois Puritan culture.

Instead, we want to be rigorous with ourselves to do right by one another but really loving of our messiness. There is no correct way of doing the moves but rather it’s noticing and re-organizing what you’re practicing towards your commitment, which in your case right now is to freedom. In many ways the moves are about becoming rather than being, as much as there is a clear there-there in somatics with our focus on embodying commitments and intentional shapes. But it’s more of a spiral than an arc. We’re not fixing ourselves for good. We’re allowing for more and more of ourselves to be intentional and congruent with our longings and with others’ longings as change continues over the course of our lives and history. That’s the beautiful hot mess of transformation. And we can get rigorous about how we do it with more awareness, intention, skill and presence. Also, the more we practice together, staying in conversation about all this, the more we can make change happen together. I have a hunch Rosa Luxembourg or Amilcar Cabral or Sylvia Rivera had deeply instructive things to say about all this. We can shape society according to the shared values we practice over and over, messily, with both love and rigor.

JASON

We can’t talk somatics without talking bodywork. Most people associate bodywork with massage. This is very different.

I lay on your table. You guide me through some breathing exercises. From there the bodywork can take a variety of forms, from the intense to the gentle. Let’s talk about the intense variety.

Sometimes you instruct me to make a strong humming sound from my chest and diaphragm. While I’m doing that you pump my torso, so the humming becomes staccato. It’s like my body is working against the force you’re coming at me with, to keep the humming steady. It feels really primal. The first couple of times it felt alien, like these animal sounds could not possibly be coming from me. It was just the kind of thing I have inhibitions around—freaking people out by doing something that’s socially off limits, wailing like an animal. I am an animal after all, and that belief is core for me and informs how I live and what I write about.

After one session of bodywork, you told me to take it easy for the rest of the day, drink a lot of water. Luckily, David was home. I curled up on the couch, and for a few hours I felt like my entire life history was rushing and swirling through my body. It was intense and unstoppable. It was scary. But it also had this cleansing quality. After that, I felt much more comfortable wailing like an animal on the table and a little more free to make an impact.

Sometimes in addition to all that, you’ll direct me to move my eyes so that I look at your fingers, then the ceiling, then your fingers—in rapid succession. Then, as if that weren’t enough, you tell me to start moving my legs, kind of like I’m riding a bike. It’s a totally disorienting experience. You explained that the goal is to disorganize me, literally scramble up my usual shaping. That makes for possible new ways to assemble my body and psyche. This is real. This totally happened for me.

I can’t really track all the magic moves you’re making while you’re doing bodywork. I’m too in the moment. But I’m aware that you’re using really particular techniques with clear aims. Your hands are busy the whole time. Your breath is steady. Your focus is total. Will you talk a little about the techniques and what you’re up to while I’m in my dazed limbic state?

SUMITRA

It’s so intriguing to me to read your description of this, Jason. Animal sounds and primal feelings indeed!

Bodywork is all about opening and de-armoring. It’s about opening up more possibility for a person towards their more chosen, purposeful shape, of course in your case, freedom in many forms.

It’s also about softening up our body’s protective armor so that it is possible to feel safe in other ways not just the ways that past trauma mandated. You brace and freeze, contracting in your throat, pulling in your shoulders and chest, pulling up from your legs, almost folding into your wound to protect it. You’ve described hiding under the sheets, keeping perfectly still as a child, no breath, so your presence wouldn’t make an impact or watching helplessly as your mother is abused.

Imagine another person’s head that bows in constant apology, a chest that quickly collapses to give up hope and trust, eyes that often narrow with suspicion, an unsmiling jaw that juts to keep people away, shoulders puffed with bravado, a pelvis tucked in to disappear oneself--you get the gist. Literary writers and visual artists who describe emotion have communicated this for centuries. And, if you look at these descriptions they make an intuitive sense to many of us, even if these are not always the specific emotions associated with the particular physical description. We assess one another all the time and whether we name it or not, often have an animal sense of each other’s armoring, decide if we’re attracted or repulsed, whether that armoring fits with our own, intuitively.

To de-armor, we want to open, ease or even disrupt the pattern or the holding to allow for more. But to disrupt what has felt safe even if it has felt limited can feel scary and uncertain. So why the hell would we do that? Because, if there is a longing for more, the point is to find new or more ways of feeling and being safe that feel less threatened. We want to regenerate safety, a wider range of safety in our emotional being. Bodywork can help do this.

So yes, you lie on the table and it’s a collaborative experience from then on, not massage although it involves suggestions I make through contact with your connective tissue, active guided breath, stretching the eyes out of their contraction like you describe, sometimes voice with the breath, sometimes moving the ribs, pulsing certain points, sometimes kicking and other movement on the table. And, yes, we talk in the midst of that. We connect, human to human. We talk about what or whom you care about, for example, or what you’re afraid of. Or what a particular feeling of release you experience or a shuddering or tingling in a part of your body might signal for you. So your speech and cognition is involved too but in a rare turn for us humans, especially those of us in our hectic everyday urban lives, we encourage those to be subservient to the emotional body, the limbic state.

JASON

The first few times we did this, it scared me--a lot. I think that’s because I’m so comfortable with my cognitive self, which can sort of hide the rest of me—that limbic stuff.

SUMITRA

Yes, sometimes bodywork can be intense and disorganizing but it can also be integrating and cohering. It depends on what the body is ready for in opening up its patterns. The intense kind that you talk about can open up a lot of memory and even plunge us into massive swirls of emotion underneath all the holding, whether old grief or fear or rage or coughing and laughter. People can shake, jaws can chatter. Or stream, where the entire body enters into a prolonged period of shuddering waves of release and opening up of long contracted muscles. It can feel wild. Yes, it can feel scary at first or magical or trippy and yet, here again, it’s oddly pragmatic and shit, it’s what’s happening. It is real. It is a weird combination of chemicals, firing synapses and evolutionary instinct. But, really it’s not weird at all. It is just us in all our glory. Our psycho-biologies -- I mean, come on, life is so incredible, isn’t it?

I remember a time when Spenta Kandawalla, my dear friend and teacher, used her fingers to soften the tissues within my first and second ribs to suggest widening my chest, right around my heart, which had felt closed so tight, so stubbornly sad. My jaw and teeth began to chatter uncontrollably for what felt like a full ten minutes. And of course, with encouragement, I let go of the inhibition and let it happen and sobbed, full body shuddering. I had been holding in such an old frozen rage and grief. It’s a pretty profound thing for human beings to be able to hold and care for one another in such vulnerable, deep emotions.

However, Staci Haines was always clear to point out that body workers don’t do catharsis. We’re not in it to milk emotion out of people as a sign of success. We're not venting bodies like steam valves. We’re increasing the tolerance of a range of emotion and energy in our bodies. Emotions can arrive into the full realm of sensation in bodywork and that can be a place from which to allow for them in all their swell and subsiding. More emotional range becomes possible. We start to feel safer and more at ease without the words that need to understand things.

A skilled body worker is not just going to mine you for the big cry or release but allow for your body to open or deepen to the next level that it’s ready for, which can be conscious or subconscious but they are deeply listening to your longing under the skin. A more emotionally expressive person might long for the capacity to hang out with themselves inside their own bodies instead, to get really internal and contain their emotions without the need to express them. It does not all look one way. Someone heady who ruminates a lot may finally feel safe enough to feel how emotions and sensations connect within them after several sessions. It’s different for different bodies. So we, as workers, stay very present to what wants to unfold on the table.

I’m in a lot of study here with a lot to still learn. I have to keep being present, centered on my own commitment, and deepen my own capacity to listen and follow every body’s rhythms, get my own grabs or triggers out of the way, understand simple and complex aspects of our anatomies more, feel more deeply into how the emotional and physical body are enmeshed in how we hold and shape and move our muscles, structure, breath and energy, the ebbs and flows over the course of our lives.

JASON

This brings me to screaming. I thought I wasn’t capable of it. My friend Dana Lyn, a brilliant musician, has this moment in a show she does with Stew and Heidi Rodewald. She’s playing violin and stops, pauses, and then screams in this extended primal way. The show is about James Baldwin, so the scream has all kinds of historical, racial, sexual, and literary resonances. The first time I saw it I was in awe. I could never let loose like that, I thought. I asked her if it was hard. She said it was fun. I told you about this. We talked about whether I should try it in your office. We decided against it. But then I was driving home after our session and I tried it. Turns out I can scream. No problem. I can scream with abandon. That was an exciting moment of new freedom. The truth is I don’t love doing it. It hurts my throat. But I love that I can do it.

SUMITRA

For you, the screaming was such a sign of longing for release. You told me the story of your friend, the one who screams. You were fascinated. It wasn’t the end game in the sense that the goal for you was not screaming itself but there was something about it that felt like doing it would give you a strong opening into and achievement of the bodily freedom you long for.

So, yes, I wanted to disorganize the highly protective and organized tendency of yours to not be a burden, to hold it together, to fear the unpredictable, to stay braced for something to go wrong. That needed to be disrupted in order for you to engage more possibility for your voice outside of writing and intellectual life, literally and figuratively. That was part one. You weren’t ready to be witnessed in the actual screaming itself, in my office. But, the car is an awesome place for a solid scream. Part 2 was on you. Screaming with abandon—how beautiful. Yes, don’t hurt your throat. But how alive you were, no?

JASON

You often ask me a direct question and say, “first thought, best thought.” This is me turning the tables. First thought, best thought: Why do you do this work?

SUMITRA

Yes, that’s what we often say as body workers, to encourage spontaneous response from the body itself. Okay. So, first thought: I do this because I want to be the deepest fight for life, the boldest love of life that I can be.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Kelly Breez for the original art. Thank you to the many people who work with generative somatics for developing the practices we discuss, including Richard Strozzi-Heckler, Staci Haines, and Spenta Kandawalla. Thank you to Glenn Zermeño for suggesting we work together. This piece wouldn't exist without him.