Autism

Neuromodulation of the Cerebellum Influences Social Behavior

Cerebellar neuromodulation restores social behaviors linked to autism in mice.

Posted December 14, 2017

A potentially game-changing new study on mice by neuroscientists at UT Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) reports that social impairments can be improved by brain stimulation of targeted areas in the cerebellum. This study, “Altered Cerebellar Connectivity in Autism and Cerebellar-Mediated Rescue of Autism-Related Behaviors in Mice,” is the cover story for the December 2017 issue of Nature Neuroscience.

Approximately one of every 68 children in the U.S. is affected by autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is often characterized by challenges with social interaction and communication along with atypical and repetitive motor behaviors. Although this study was conducted using a mouse model, the researchers are optimistic that the findings have human implications regarding the use of cerebellar neuromodulation for the treatment of autism.

Senior author Peter Tsai is an Assistant Professor of Neurology & Neurotherapeutics at UT Southwestern Medical Center's Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute who cares for children with autism and cerebellar disorders. Tsai conducted this research along with first author Catherine Stoodley, from the Department of Psychology and Center for Behavioral Neuroscience at American University, and neuroscientists at UTSW.

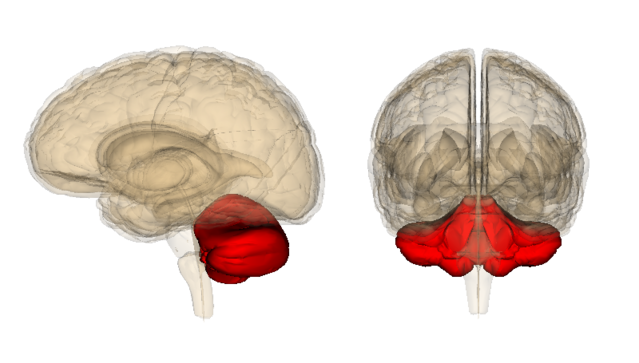

These findings by Stoodley et al. provide fresh evidence that the cerebellum—which has long been considered by most experts to only play a role in fine-tuning coordinated muscle movements—plays a significant role in driving social behaviors and ASD.

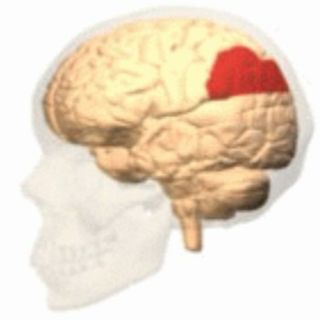

As Tsai explained in a statement, "This area of the brain has not received the attention it deserves in regards to understanding autism. Most of the focus of autism research has been on the cortex, a region of the brain associated with cognition.”

Cerebellar abnormalities have been implicated in previous autism studies. However, this is the first clinical study to show that neuromodulation of a specific region within the cerebellum has the power to improve autism-like behaviors in mice and could improve social behaviors in children with ASD.

To gain a better understanding of the role that the cerebellum plays in mediating these behaviors, Tsai and collaborators used neuromodulation and other state-of-the-art techniques to illuminate that humans and mice have parallel connections between the Right Crus I (RCrusI) located in the right hemisphere of the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex's inferior parietal lobule.

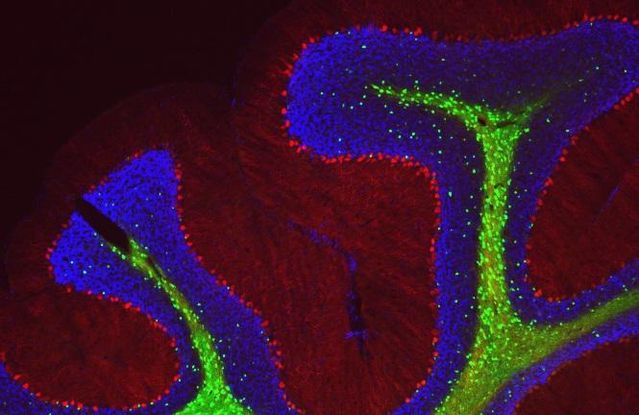

More specifically, the researchers found that atypical RCrusI–inferior parietal lobule structural connectivity was evident in Purkinje neurons. Another prong of this study used chemogenetically mediated inhibition of RCrusI Purkinje neuron activity in mice to generate ASD-related social, repetitive, and restricted behaviors.

That being said, the authors emphasize, "Although RCrusI is functionally connected with ASD-implicated circuits, the contribution of RCrusI dysfunction to ASD remains unclear." This research does reveal that targeted neuromodulation of the cerebellar Right CrusI domain is correlated with improved cerebellar functional connectivity to the inferior parietal lobule housed in the cerebral cortex.

"This is potentially quite a powerful finding," according to Tsai. "From a therapeutic standpoint, this part of the cerebellum is an enticing target. And although neuromodulation would not cure the underlying genetic cause of a person's autism, improving social deficits in children with autism could make a huge impact on their quality of life."

The next step for the UTSW research team is to ensure the same neuromodulation technique used on mice would be safe to use on children with ASD. In the past, doctors have safely applied cerebellar neuromodulation to treat adults with schizophrenia. But this brain stimulation technique has not yet been clinically studied in children with autism. The good news is that Tsai and colleagues will begin conducting these type of clinical trials sometime soon at UT Southwestern's Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities.

In conclusion, the authors write: "Together, these studies reveal important roles for RCrusI in ASD-related behaviors. Further, the rescue of social behaviors in an ASD mouse model suggests that investigation of the therapeutic potential of cerebellar neuromodulation in ASD may be warranted."

Tsai summed up the main takeaway of this research: "Our findings have prompted new thoughts on how the cerebellum may be involved in autism and most importantly suggest that the cerebellum could be a therapeutic target for treatment."

References

Stoodley, Catherine J., Anila M. D’Mello, Jacob Ellegood, Vikram Jakkamsetti, Pei Liu, Mary Beth Nebel, Jennifer M. Gibson, Elyza Kelly, Fantao Meng, Christopher A. Cano, Juan M. Pascual, Stewart H. Mostofsky, Jason P. Lerch, and Peter T. Tsai. "Altered Cerebellar Connectivity in Autism and Cerebellar-Mediated Rescue of Autism-Related Behaviors in Mice." Nature Neuroscience (December 2017) DOI: 10.1038/s41593-017-0004-1

Catherine J. Stoodley and Jeremy D. Schmahmann. "Evidence for Topographic Organization in the Cerebellum of Motor Control Versus Cognitive and Affective Processing." Cortex (2010) DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.11.008