Alcoholism

Michael Phelps’ Heroic Journey Goes Far Beyond Gold Medals

By revealing lessons about hitting rock bottom—Phelps has enlightened our world.

Posted August 15, 2016

Michael Phelps secured his place as a mythic legend at the 2016 Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He is now the most-decorated Olympian of all time. This week, Phelps retired from an epic swimming career that spanned five Olympic Games and garnered him 28 medals, 23 of them gold. No other modern-era athlete in any sport has won more than nine gold medals.

Since the beginning of the Olympics in Ancient Greece millennia ago, Leonidas of Rhodes in 152 B.C. is the only person who historians say holds a candle to Phelps’ gold medal haul. In fact, Phelps has surpassed Leonidas 2,000 year old record and secured his place in the history books for eternity.

Michael Phelps is the stuff that mythology is made of on many levels. In a previous Psychology Today blog post, from March 2016, “Michael Phelps and the Romance of Archetypal Journeys," I explored how Phelps’ quest to win Olympic medals in Rio this summer held many unexpected clues about successfully completing “The Hero’s Journey.” That post was inspired by Phelps’ breathtaking “Rule Yourself” video clip released last spring.

Ever since seeing the video montage above (which brings tears to my eyes every time I watch it) I’ve been hoping that the blood, sweat, and tears that Phelps poured into his training for the 2016 Olympics would have a fairy-tale ending for him and his family.

It would have been tragic and heartbreaking to see Phelps' last hurrah as a 31-year-old Olympian make him seem like an over-the-hill 'has been' who was well past his prime clinging to his glory days. As we now know, the outcome of Phelps’ Rio performances couldn’t have been more awe-inspiring and well-deserved.

What Is “The Hero’s Journey”?

In archetypal storytelling and the academic study of comparative mythology, the hero's journey is a common formula that involves a protagonist (the hero or heroine) going on an odyssey or adventure far from home. On this odyssey he or she faces a life-altering crisis, prevails by seizing the ‘holy grail’ or some type of magic elixir, and returns home as a transformed human being. Joseph Campbell is credited with coining the term “monomyth” or "the hero’s journey” in his 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

You don't need to be a world-famous athlete or some kind of extraordinary human being to embark on an archetypal heroic journey. The hero's or heroine's journey happens to varying degrees anytime you go on a quest for some type of holy grail that takes you out of your comfort zone.

For example, as I was coming of age as a young athlete, I was deeply inspired by Joseph Campbell’s classic 1988 PBS series and accompanying book, The Power of Myth. Campbell’s exploration of universal archetypes that play out again and again in our lives created a type of crystal ball that allowed me to foresee the short- and long-term consequences of the decisions I made every day—in both sport and life.

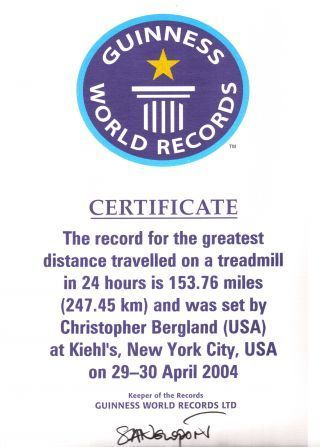

Campbell’s writings helped me romanticize my athletic competitions as some type of mythic quest. By the time I was 37, I'd completed dozens of Ironman triathlons around the world, run the Badwater Ultramarathon a couple times, won the Triple Ironman (7.2-mile swim, 336-mile bike, 78.6-mile run done consecutively) three years in a row, and broken a Guinness World Record.

To onlookers, breaking a Guinness World Record by running 153.76 miles in 24 hours would seem like the apotheosis of my lifetime accomplishments. (Apotheosis means, ‘the highest point in the development of something, culmination or climax; or, the elevation of someone to divine status; derification.’)

But, I knew that my journey was really just beginning. To complete the hero's journey I would have to cross the return threshold and come home to a world that didn't seem mundane, but rather filled with possibilities. That is why I decided to have a child. I wanted to dedicate myself to becoming a father and breaking the generational patterns of dysfunction that surrounded me growing up. I also decided to reinvent myself as a writer.

Obviously, I'm a flea in comparison to most Olympic athletes, especially Michael Phelps. Nonetheless, I think there are universal lessons we can all benefit from by looking at our life’s trajectory through the lens of the 12-phases of the hero’s journey.

Crossing the Return Threshold and Coming Home Is the Most Underrated Stage of the Hero’s Journey

After retirement or losing popularity with fans, athletes, and other public figures on the hero’s journey often have difficulty returning from the extraordinary world back home and re-acclimating to the ho-hum aspects of everyday life.

The final stage of successfully completing the hero’s journey is described as “The Crossing of the Return Threshold." During this stage of his or her odyssey, the hero must return back to the work-a-day 'ordinary' world after the thrill of exploring exotic and far away places physically, psychologically, and spiritually. This reentry from the stratosphere can be a death-defying challenge.

I have a hypothesis that one reason so many musical superstars self-implode like supernovas is the challenge of returning back down to earth and melding back into the ordinary world is just too much. Especially, after the rush of performing in the limelight in front of thousands of adoring fans at the peak of your fame and adoration.

Watching Phelps interviews over the past few weeks has helped me fill in some of the psychological gaps of how an athlete retires gracefully that were unclear until now. Hopefully, looking at Phelps’ heroic journey through the lens of the ‘monomyth’ will help others achieve greatness, cross the return threshold to come home, and complete their hero’s journey successfully.

As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve never felt as depressed and hollow inside as I did the day after reaching the zenith of my athletic career. Like a climber who has summited Everest, there was no place higher for me to go, and it made me feel hopeless inside.

The first thing I started doing to fill this void after retiring from athletic competition was binge drinking. This was something I had learned how-to do really well at boarding school and never resolved in analysis. Sports had become a substitute for the high I would get from drugs and alcohol when I was seventeen. I realized when I retired from sports training competitions—and no longer had a constant runner's high—that alcohol was my Achilles heel.

Much like the ecstatic process of aerobic exercise—binge drinking creates superfluidity between my mind, body, and brain on a neurobiological level. Alcohol makes me feel as if I’m existing without any friction or viscosity, much like I did when I was training for ultra-endurance events 24/7. I have a hunch that Michael Phelps might be cut from the same cloth.

Of course, binge drinking takes a heavy toll, wreaks havoc on someone’s existence, and is unsustainable. Because I’ve been there myself, I felt very simpatico with Phelps after the 2012 Olympics when he retired and his life seemed to go off the rails. After his second DUI in September of 2014, Phelps entered rehab. I wrote about the issues surrounding this in a Psychology Today blog post, “The Neuroscience of Binge Drinking.”

In an August 2016 interview with Bob Costas, just prior to competing in the Rio Olympics, Phelps described various stages of his life and his archetypal journey in a heart-to-heart discussion:

Bob Costas: “You’ve said that without swimming, your sense of yourself, your identity, was lost, and you had no real direction. And this led to some dark places, right?”

Michael Phelps: “Oh my gosh. For so long I just looked at myself as a kid that was talented who would go up and down the pool. Very little else. Very few people really knew who I was. I took some wrong turns and ended up in some of the darkest places you could ever imagine. Places I hope nobody else ever goes.

I still remember the days locked up in my room, not wanting to talk to anybody, not wanting to see anybody. Really not wanting to live. I was on a downward spiral and I was on the express elevator to the bottom floor, wherever that might be. And I found it. . . I think for me, I really had to reach my absolute rock bottom to get a wake up call. Those mornings not wanting to be alive. I just decided that something needed to change."

Bob Costas: “So you go to a rehab facility . . . What’s the most important thing you learned?”

Michael Phelps: "I went through this process where we tried to connect with our inner child, and I had so many vivid memories of me at the age of seven, eight, nine. It was kind of cool to realize that the kid is still going to come out in this, and that’s who we really are. I remember, I went through a box of tissues that day, just pouring emotions out. Once we brought all of that stuff out, I literally felt like a new person.

It’s like you’re walking down the street with a backpack full of weights. One by one you just remove weight, after weight, after weight. That’s how I felt. I literally felt like I was walking on clouds."

Bob Costas: (Voiceover) “Phelps says he hasn’t consumed alcohol since Oct. 4, 2014. Since then, he’s focused on repairing many relationships in his life. In particular, reconnecting with his father, Fred . . . Since leaving rehab, he’s gotten engaged and he’s had a son. After emerging from that dark time in his life, he says he’s now as happy as he’s ever been.”

Michael Phelps: “The life that I live now is a dream come true. I’m able to do what I love in the pool and out of the pool. I have a beautiful baby boy, a gorgeous fiancé, a great family, I’m closer to the people who like me and love me for me than I ever have been in my life—and I would never change that. I truly am living a dream come true.”

Conclusion: The Chinks in a Hero's Armor Are Often a Source of Inspiration

For me, the most refreshing thing about Phelps being the most-decorated Olympian of all time is his lack of hubris and willingness to make himself completely vulnerable. Phelps has the courage to reveal his innermost fears and traumas. As Brené Brown reminds us, the key to feeling worthy of love and belonging is found in living wholeheartedly and making yourself vulnerable.

In my opinion, Michael Phelps’ accomplishments in the pool pale in comparison to what he’s teaching us all about: getting in touch with our inner child, forgiving parents who have let you down, forgiving ourselves for our failures, and breaking patterns of paternal neglect.

In Japanese culture there is a concept called “wabi-sabi,” which represents a Japanese aesthetic and mindset based on embracing imperfection. Wabi-sabi reminds us that nonconformity and irregularity can be much more eye opening than cookie-cutter perfection. In many ways, Phelps represents the power of wabi-sabi to me. He's shown us all that our heroes and heroines don't have to be perfect. Styrofoam, phony and guarded people are boring. Thank you for letting your guard down, and showing us who you really are Michael Phelps. Bravissimo!

In many ways, phase two of Phelps’ heroic journey is just beginning... As he said in an interview moments after winning his final gold medal, “It’s not the end of a career. It’s the beginning of a new journey. And, I’m just looking forward to that.”

To read more on this topic, check out my previous Psychology Today blog post,

- "The Dark Side of Mythic Quests and the Spirit of Adventure"

- "Dad's Psychological Well-Being Impacts His Kids' Development"

- "Why Do So Many Superstars Self-Destruct Like Supernovas"

- "Love What You Do, Pour Your Heart Into It and You'll Succeed"

- "Peak Experiences, Disillusionment, and the Joy of Simplicity"

© 2016 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.