Creativity

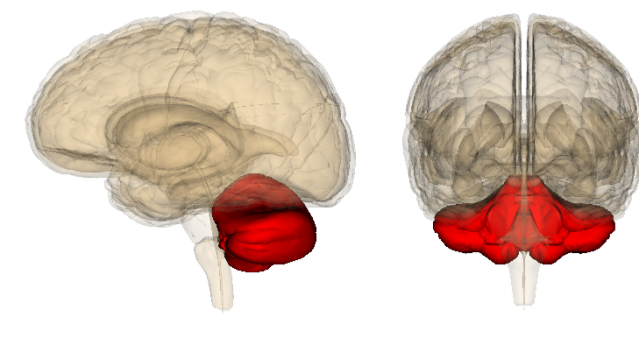

The Cerebellum May Be the Seat of Creativity

Researchers link creativity to the cerebellum for the first time.

Posted May 29, 2015

In a revolutionary discovery, new research from Stanford University published on May 28, 2015 reports that the cerebellum may be the seat of creativity. Traditionally, the “right brain” has been considered the seat of human creativity. The breakthrough study from Stanford literally turns our concepts of creativity upside-down by putting the cerebellum (Latin: little brain) in the spotlight as a prime driving force of the creative process.

For decades, the predominant split-brain model has been based on the idea of a “left brain-right brain” divide between the two hemispheres of the cerebrum. New research shows that the left and right hemispheres of the cerebellum may also play a crucial role in creativity and the creative process.

Cerebrum in red.

The cerebellum is traditionally viewed as home to muscle memory, coordination, and the reason "practice makes perfect," but hasn’t been considered by most experts to play a role in the creative process. The new study also suggests that “overthinking” (relying exclusively on the brain’s higher-level, executive-control centers held in the cerebrum) actually impairs, rather than enhances, creativity.

The study’s lead author, Manish Saggar, PhD, summed up the findings of the study by saying, “The more you think about it, the more you mess it up.” This is exactly what tennis legend Arthur Ashe would describe as “paralysis by analysis.”

The May 2015 study, “Pictionary-Based fMRI Paradigm to Study the Neural Correlates of Spontaneous Improvisation and Figural Creativity,” was published in the the journal Scientific Reports. The new Stanford study was a collaboration between the School of Medicine and Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (commonly known as the “d.school”).

This study is the first to find direct evidence that the cerebellum is involved in the creative process. In a press release, the study’s senior author, Allan Reiss, MD, professor of radiology and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, described the study,

Our findings represent an advance in our knowledge of the brain-based physiology of creativity. We found that activation of the brain’s executive-control centers—the parts of the brain that enable you to plan, organize and manage your activities—is negatively associated with creative task performance. Creativity is an incredibly valued human attribute in every single human endeavor, be it work or play. In art, science and business, creativity is the engine that drives progress. As a practicing psychiatrist, I even see its importance to interpersonal relationships. People who can think creatively and flexibly frequently have the best outcomes.

Jeremy D. Schmahmann, MD, an expert on the cerebellum from Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in this study, commented on the new findings from Stanford in a press release by saying “These are intriguing results, and it will be interesting to see how this relationship of cerebellum and artistic and intellectual creativity plays out in future studies.” Two of Schmahmann’s patients are artists who had their creativity sapped by strokes that damaged the cerebellum.

The research at Stanford on creativity and the brain began three and a half years ago, when Grace Hawthorne, an associate professor of design at Stanford University Institute of Design, approached Allan Reiss to explore new ways to objectively measure whether or not her design class actually enhanced students’ creativity.

Mannish Saggar, from the Center for Interdisciplinary Brain Sciences Research and Department of Psychiatry at Stanford, came up with the idea of recreating Pictionary for the study. Pictionary is a game in which players draw sketches to illustrate words while teammates shout out guesses about what word they’re trying to draw.

Participants in the experiment were placed in a fMRI scanner and asked to draw either “action words” (such as “vote,” “levitate,” “snore” and “salute”) or (as a control) a simple zigzag line. Drawing a zigzag line engaged the fine-movement and attentional-focus areas of the brain, but didn’t require creative processing.

Later, the drawings were rated by a panel of experts for creativity, accuracy, and other parameters, and then compared to the brain imaging scans. The fMRI results on creativity surprised the Stanford team. In an unexpected finding, the increased perception of difficulty for drawing a word was correlated with increased activity in the cerebrum's left prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain associated with executive function.

Interestingly, high creativity scores were associated with lower activity in the cerebrum's "left brain" combined with higher activation in the cerebellum, but not necessarily in the cerebrum's right hemisphere or "right brain."

The Stanford Researchers Were Surprised by the Connection Between the Cerebellum and Creativity

The heightened activity in the cerebellum was unexpected. The Stanford researchers hypothesize that the cerebellum "may be able to model all new types of behavior as the more frontally located cortical regions make initial attempts to acquire those behaviors. The cerebellum then takes over and, in an iterative and subconscious manner, perfects the behavior, relieving the cortical areas of that burden and freeing them up for new challenges." Reiss summarized the findings saying,

It’s likely that the cerebellum is an important coordination center for the rest of brain, allowing other regions to be more efficient. As our study also shows, sometimes a deliberate attempt to be creative may not be the best way to optimize your creativity. While greater effort to produce creative outcomes involves more activity of executive-control regions, you actually may have to reduce activity in those regions in order to achieve creative outcomes.

The fact that activity in the cerebellum decreased when participants faced a cognitively challenging task, but increased when the task required little conscious thought supports the hypothesis that the cerebellum plays a role in cognition in the same way it plays a role in motor control. If this is true, Reiss surmises, “it’s likely the cerebellum is the coordination center of the brain, allowing other regions to be more efficient.”

Reiss’ observations echo exactly what Jeremy Schmahmann has been saying about the cerebellum for years. Schmahmann is the father of a revolutionary cerebellar theory he calls “Dysmetria of Thought” which is a hypothesis that the cerebellum fine-tunes and coordinates our learning and thinking just like it fine-tunes and coordinates muscle movements.

Recently, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post, "The Cerebellum Deeply Influences Our Thoughts and Emotions,” based on cutting edge cerebellar research Schmahmann is conducting on ataxia and "Dysmetria of Thought" at Massachusetts General Hospital at Harvard Medical School. If you'd like to watch Schmahmann explain his theory on "Dysmetria of Thought" check out this YouTube video:

The Cerebellum Is a Prime Driving Force in My Life

Personally, I feel vindicated by the findings from Stanford University which have found a link between creative problem-solving and heightened activity in the cerebellum for the first time.

My father, Richard M. Bergland, MD, was a neuroscientist and neurosurgeon who was one of the early pioneers of the widely accepted "left brain-right brain" model. Betty Edwards actually consulted with my father for her bestselling book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, and cites my father's book The Fabric of Mind, in which he said,

You have two brains: a left and a right. Modern brain scientists now know that your left brain is your verbal and rational brain; it thinks serially and reduces its thoughts to numbers, letters and words… Your right brain is your nonverbal and intuitive brain; it thinks in patterns, or pictures, composed of ‘whole things,’ and does not comprehend reductions, either numbers, letters, or words.

Later in his life, my father became convinced that the cerebellum was responsible for much more than just our body’s muscle movements and coordination. Unfortunately, most of his peers in academia and the medical establishment labeled my father a heretic when he moved away from the "left brain-right brain" model and tried to put the cerebellum in the spotlight.

My dad passed away in 2007. After my father died, I made a vow that I would do everything in my power to stay plugged-in to the latest neuroscientific findings and do my best to report these ideas to a general audience. That is why I am writing this blog post. For the past decade, I’ve been waking up every day hoping for news on the cerebellum that would vindicate the stand my father and I had taken on the importance of the cerebellum.

While writing the manuscript for The Athlete’s Way in 2005, my dad and I worked closely together to create a new split-brain model we called “up brain-down brain” as a way to challenge the prevailing notions of “left brain-right brain.” On page xiii of the introduction to The Athlete's Way, from over a decade ago, I described my personal relationship to the cerebellum saying,

When I was growing, up neuroscience was a constant topic of conversation, and discussions with my father have continued over the years. The Athlete’s Way is based on the hypothesis that humans have two brains: an animal feeling-and-doing brain called the cerebellum (Latin: little brain), and a human thinking-and-reasoning brain called the cerebrum (Latin: brain).

My dad and I refer to this brain model as “down brain-up brain.” The up brain is the cerebrum based on its position north of the midbrain, which is midway between the two brains. The cerebellum is the down brain, the southern hemisphere in the cranial globe as it were, based on its position south of the midbrain. The simple names down brain-up brain may sound grammatically incorrect but are a direct and cogent response to the 1970s split-brain model of ‘“left brain-right brain."

As I will show you throughout this book, the salient divide in the brain is not from east to west or from right to left. Instead, it is from north to south. New brain imaging unavailable in the 1970s has confirmed the power of the cerebellum to do more than just keep our balance, posture, coordination, and proprioception, a sense of body position.

The cerebellum is our emotional and intuitive center and may even hold our personal and collective unconscious ... In trying to decode the cerebellum, I have uncovered new ideas about the mysterious and exotic little brain. The cerebellum has been hidden under the surface for far too long. This book puts the cerebellum in the spotlight.

Unfortunately, my book was a total bomb. A decade ago, the ideas I presented about the cerebellum were flat-out rejected by both the medical establishment and my athletic peers. I was highly disappointed, but took solace in my editor Diane Reverand’s reassuring words about being patient and not giving up on my beliefs. Diane said, “Chris, it often takes ten years for people to catch up to ideas that are ahead of their time. Keep researching and writing about the cerebellum.” Reading about this Stanford research yesterday reaffirmed my faith in Diane's words of wisdom.

Yesterday, I was running on the treadmill when my phone dinged with the typical Google Alerts sound that there was an update about the cerebellum on the world wide web. Needless to say, I literally almost flew off the back of the treadmill when I read about the new study from Stanford linking creativity and the cerebellum. In many ways, this is the study I’ve been hoping to read for over a decade. Thank you Allan Reiss, et al!!

Conclusion: The Cerebellum May Take Center Stage in the 21st Century

The new study from Stanford University linking the cerebellum and creativity may be the tipping point for a new appreciation on the power of our mysterious "little brain." The cerebellum is only 10% of brain volume but houses over 50% of your brain's total neurons. Based on this disproportion, my father would often say, "We don't know exactly what the cerebellum is doing, but whatever it's doing, it's doing a lot of it."

The new research by people like Jeremy Schmahmann at Harvard Medical School and Allan Reiss at Stanford University is beginning to provide answers to "what the cerebellum is doing." This is a very exciting time to be studying the cerebellum, it seems that every week there is a new report on the importance of the hereofore underestimated cerebellum.

Stay tuned to my Psychology Today blog posts for updates. If you'd like to read more on the cerebellum, check out my previous Psychology Today posts:

- "The Neuroscience of Imagination"

- "Why Does Walking Stimulate Creative Thinking?"

- "The "Right Brain" Is Not the Only Source of Creativity"

- "The Cerebellum Deeply Influences Our Thoughts and Emotions"

- "The Wacky Neuroscience of Forgetting How to Ride a Bicycle"

- "Why Do Drunk People Stumble, Fumble, and Slur Their Words"

- “The Cerebellum, Cerebral Cortex, and Autism Are Intertwined”

- "How Is the Cerebellum Linked to Autism Spectrum Disorders?"

- "Research Links Autism Severity With Motor Skill Deficiencies"

- "The Neuroscience of Calming a Baby"

- "How Are Purkinje Cells in the Cerebellum Linked to Autism?"

- "Autism, Purkinje Cells and the Cerebellum Are Intertwined"

- “How Is the Cerebellum Linked to Bipolar Disorder?”

- "How Does Body Posture Affect Early Learning and Memory?"

- "The Cerebellum Holds Many Clues for Creating Humanoid Robots"

- "Better Motor Skills Linked to Higher Academic Scores"

- "Hand-Eye Coordination Improves Cognitive and Social Skills"

- "Childhood Family Problems Can Stunt Brain Development"

- "Is Cerebellum Size Linked to Human Intelligence?"

- "Primitive Brain Area Linked to Human Intelligence"

- "The Neuroscience of Knowing Without Knowing"

- "The Mysterious Neuroscience of Learning Automatic Skills"

- "The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure"

- "How Does the Vagus Nerve Convey Gut Instincts to the Brain?"

- "Why Does Overthinking Cause Athletes to Choke?"

- "Toward a New Split-Brain Model: Up Brain-Down Brain"

- "Neuroscientists Discover How Practice Makes Perfect"

- “Why Is Dancing So Good For Your Brain?”

- “The Neuroscience of Madonna’s Enduring Success”

- "No. 1 Reason Practice Makes Perfect"

- "How Does Practice Hardwire Long-Term Muscle Memory?"

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete's Way blog posts.

© Christopher Bergland 2015. All rights reserved.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.