Stress

Social Disadvantage Creates Genetic Wear and Tear

Disadvantaged environments can shorten telomeres and alter genes by age nine.

Posted April 16, 2014

Last week, I had the opportunity to speak with Daniel Notterman and Colter Mitchell about their paper titled, "Social Disadvantage, Genetic Sensitivity and Children's Telomere Length," which was published online April 7 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This paper makes important new contributions to current “epigenetic” research on the connection between a person’s social environment and well-being based on the shortening of telomeres.

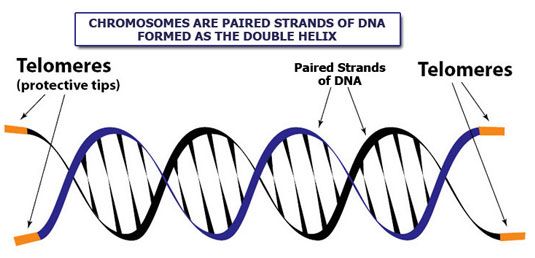

What are telomeres? Every chromosome in the human body has two protective caps on the end known as telomeres. As telomeres become shorter, their structural integrity weakens, which causes cells to age faster and die younger.

Multiple studies have shown that the stress caused by things like: untreated depression, social isolation, long-term unemployment, and high anxiety can speed-up the aging process by shortening the length of telomeres which can lead to poor health outcomes. I have a hunch that the study of epigenetics and telomere length may be the next wave for better understanding mind-body-environment connections.

Will Telomere Length Be the Future Biomarker of Well-Being?

This study brings researchers closer to understanding the importance of psychological and environmental stress during childhood and how these genetic imprints can be detrimental for long-term health. Using telomeres as a biomarker as the participants of this study grow older will be a valuable tool for assessing the long-term impact of childhood disadvantage and familial stress.

For this study, the researchers wanted to focus on African American boys because past studies have shown that boys may be more sensitive to their environment than girls. The team limited their sample to 40 boys who participated in the Fragile Families study and met the following criteria: they had provided saliva samples at age 9; their mothers self-identified as black or African American; and complete information was provided about their social environments.

Of the final sample, half of the boys were raised in disadvantaged environments, which the researchers characterized by such factors as: low household income, low maternal education, an unstable family structure, and harsh parenting.

In the first unexpected discovery, the researchers found that growing up in a disadvantaged environment was associated with 19 percent shorter telomeres when compared to boys growing up in highly advantaged environments. For boys predisposed to being sensitive to their environment, this negative association was even stronger.

Dopamine and Serotonin Pathways Linked to Environmental Sensitivity

The other significant finding of this study is that there appears to be an association between the social environment and telomere length (TL) which is specifically moderated by genetic variations within the serotonin and dopamine pathways.

Boys with the highest genetic sensitivity to chronic stress had the shortest TL when exposed to disadvantaged environments and the longest TL when exposed to advantaged environments. To their knowledge, the researchers state that this report is the first to document a gene–social environment interaction for telomere length.

The researchers found that boys with genetic sensitivities related to serotonin and dopamine pathways have shorter telomeres after experiencing stressful social environments than the telomeres of boys without these genetic sensitivities.

Lead author Daniel Notterman, Professor of Pediatrics and Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Penn State College of Medicine, and Visiting Professor of Molecular Biology at Princeton, said the researchers still aren’t exactly sure of the causal effect for the changes in the serotonin and dopamine pathways.

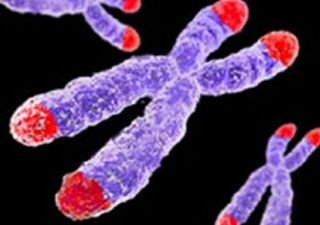

Telomeres in red.

"Our report is the first to examine the interactions between genes and social environments using telomeres as a biomarker," Notterman said. "We also demonstrate the utility of using saliva DNA to measure children's telomere length. This is important because most telomere research uses blood, which is much more difficult to collect than saliva. Using saliva is easier and less expensive, allowing researchers to collect telomere samples at various points in time to see how social environment may be affecting DNA."

In a phone conversation, Notterman clarified to me that measuring the length of telomeres is a research tool that confirms the importance of early interventions to reduce the impacts of stressful childhood environments. There is still a question though if telomere length is the actual cause of the ill-effects or just a biomarker for a more complex chain reaction.

Last week, I also had an opportunity to speak with Dr. Colter Mitchell, a co-author of the paper from the University of Michigan, whose research focuses on the causes and consequences of different types of family environments. Mitchell examines how social context such as neighborhood resources and values influence family processes and how epigenetics can influence well-being and overall health.

His research also includes the development of new methods for integrating the collection and analysis of biological and social data. "Our findings suggest that an individual's genetic architecture moderates the magnitude of the response to external stimuli—but it is the environment that determines the direction," says Mitchell.

Colter Mitchell points out that it is striking to see telomere shortening in children as young as age 9 because you are talking about accelerated aging or stress-mediated wear and tear on your body. These genetic imprints make someone more vulnerable to all kinds of illnesses and diseases ten or twenty years down the road. The health care costs for treating these illnesses in years to come will be astronomical.

Conclusion: We Can Pay Now or We Can Pay More Later

Environmental and psychological stress can alter genes throughout a lifespan. This study makes groundbreaking advances in the awareness that social disparities can shorten the length of telomeres starting at a very young age. The team plans to expand its analysis to approximately 2,500 children and their mothers to see if these preliminary findings hold true.

The most important conclusion is that stressful upbringings can leave imprints on the genes of children. Chronic stress during youth triggers physiological weathering that can lead to premature aging, increased risk of disease, and earlier mortality.

The researchers repeatedly emphasized their surprise that the biological weathering effects of chronic stress can be seen by the age of 9. Colter Mitchell concluded that from a social science and public policy perspective he hopes this study motivates people to make reducing childhood social disadvantages a top priority saying, "We can pay now, or we can pay more later. But we will pay for the effects of early life disadvantage at some point."

Huge thanks to Daniel Notterman and Colter Mitchell for taking time out of your busy schedule to speak with me about your current research. Thank you for coordinating Rose Huber. Much appreciated!

If you’d like to read more about this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Untreated Depression Linked to Telomeres, Aging, and Disease”

- "Emotional Distress Can Speed Up Cellular Aging"

- "Parental Warmth Is Crucial for a Child's Well-Being"

- "Childhood Family Problems Can Stunt Brain Development"

- "Loving Touch Is Key to Healthy Brain Development"

- "What Tactics Motivate Bullies to Stop Bullying?"

- “Meditation Has the Power to Alter Your Genes”

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.