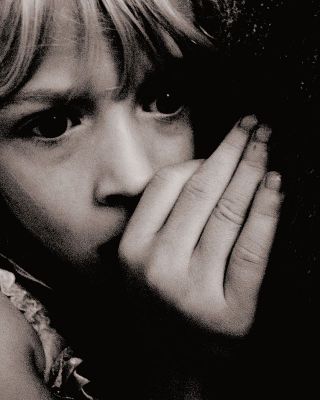

Trauma

Dealing With Psychological Trauma in Children, Part 2

Answers from neuroscience, community initiatives, and clinical trials

Posted September 25, 2014

Last week, I introduced Dr. Victor Carrion in the first entry of a three-part blog series on the impact of psychological trauma on children. Dr. Carrion is a Professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine and Director of the Stanford Early Life Stress Research Program at the Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford. His research focuses on the interplay between brain development and stress vulnerability. He has developed treatments that focus on individual and community based interventions for stress related conditions in children and adolescents that experience traumatic stress. This week, Dr. Carrion discusses how childhood PTSD differs from adulthood PTSD, the neuroscience of childhood PTSD, and common misperceptions regarding the impact of traumatic stress on child development.

SJ: How does childhood PTSD differ from PTSD in adults?

VC: Immediately, when we look at the first criterion for diagnosing PTSD, we already have an issue when it comes to kids. Criterion A requires that the traumatic event make you feel as though your life is in danger/threatened. But if you are younger than 7 or 8, you may not understand death as something that is universal and something that is irreversible.

One of the studies that we did is that we looked at children who had experienced separation or loss and were in that age group and compared them with kids that had experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse, and also had functional impairment. They really did not differ in terms of the amount of functional impairment that they had in their lives, in their personal relationships, and the amount of distress and so forth. So for children younger than 8, what I am saying is that separation or loss is considered a traumatic event, even if they might not have a full understanding of death or loss.

The symptoms of PTSD, in children as well as in adults, are mostly on and off. They are not there all the time and they tend to be triggered by cues. When those cues or triggers are there, that is when you see the symptoms. This becomes problematic if you are conducting a trial and at the end of the trial this group looks like it is doing well, it may be the case that the treatment worked but it might also be the case that there were no triggers/cues around those kids at that time. That is one of the reasons why we need to know about the neurofunctionality or the neuroscience of how traumatic stress impacts development.

For kids it is still a balance between internal and external resources, and it is like a mathematical equation. So you may have a lot of coping and strength and that may be able to help you overcome the lack of support you have in your life or you may have total perfect support but you have so many risk factors to begin with, like a previous history of trauma exposure or family history of anxiety disorder, that you are more likely to have a post traumatic reaction. I am calling it a post traumatic reaction, not necessarily PTSD, because some of the work that we have done and also work done by Dr. Michael Scheeringa at Tulane University shows that children do not have to have all the criteria for PTSD listed in the DSM to experience functional impairment. For example, we showed that kids that have PTSD compared to kids that have a history of trauma and symptoms in 2 of the clusters are equally impaired. We still have work to do in terms of how we develop this diagnostic criterion for children. That is one of the things that Michael has done. He has proposed a number of criteria that have less symptoms and also that some symptoms might be somewhat different in children compared to adults.

SJ: In terms of the neuroscience of PTSD, how might this look in terms of impact on child development from a psychophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroendocrinological point of view?

VC: One of the things that have been studied for a long time is the autonomic nervous system in children as well as in adults. It seems that those who have PTSD are actually a heterogeneous group and that physiology may help us differentiate between kids that dissociate versus all the kids that might display symptoms of aggression. For example, the kids that dissociate seem to have a lower heart rate when narrating a stressful event or a stressful story. Whereas, those that do not dissociate seem to have increased heart rate, but increased heart rate does not seem to be a good marker because it depends where your baseline is. What seems to be a good marker is how long is the latency? I.e., how long it takes you to return to your baseline heart rate after a stressor. So, if the stressor increases your heart rate, kids that are vulnerable or have PTSD will take longer in coming back to a baseline heart rate.

We concentrated on looking at cortisol and identifying what would be a good cortisol marker for these kids. What we find is that these kids have the normal circadian rhythmicity that you would expect (i.e., higher at the beginning of the day and going down at the end of the day) but then at the end of the day it seems to be elevated so these kids have high levels of cortisol. That is what we found about 10 years ago, but what we found out years later is that that variable of “time since trauma” is very important.

What we did is we looked at a big sample of kids and we looked at those that had had trauma during the past year and those that had trauma prior to that year. We hypothesized that our theory of increased cortisol was going to hold true for the kids that had it in the past year but not for the others. What we actually found was exactly that and we found 2 reverse correlations where if you had events in the past year, the higher your cortisol, the higher your symptoms of PTSD. Whereas, for the other individuals that had experienced trauma from a long time ago and were still with symptoms of PTSD, the more symptoms, the lower the level of cortisol.

But in general, I would say, that high pre-bedtime (before you go to bed) cortisol in kids, I am starting to think of that as a marker of pediatric PTSD.

Now, if you have these high levels of cortisol, the next normal question was to see what is going on in the brain because of the potential neurotoxicity of cortisol at high levels every day, right? So, we looked at kids who were experiencing chronic trauma, i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing a lot of violence.

Cross sectionally there were no significant findings. But in 2007, we followed 15 kids for 1-1 ½ years and we saw that there was a correlation between high cortisol (pre bedtime), cortisol, and decreased volume from time 1 to time 2 of the hippocampus.

Of course, the hippocampus is important for memory storage and retrieval so we did a task in functional MRI, a verbal declarative memory task, to look at encoding and retrieval in kids. We saw that the control/healthy group, with no history of trauma and no PTSD symptoms, was activating significantly more hippocampus than the PTSD kids were. So we were not seeing the volume differences but, functionally, you can see that the hippocampus really does not work as well in kids with PTSD.

We then decided to look at emotional regulation. We did the faces task and saw that kids that have PTSD activate their amygdala significantly earlier when viewing an angry face. When viewing a fearful face, there was a trend for their pre-frontal cortex to not be as activated as it was in the healthy controls. But the interesting thing about the amygdala activation is that, potentially, what we are talking about is a neuro functional marker of hyperarousability for these kids who have a history of exposure to interpersonal violence. For these kids, the face of someone angry is a cue/trigger and we here see the amygdala getting activated.

So then, we started thinking that treatments that treat these kids better pay attention to emotional regulation, memory processing, and executive function. The other thing we realized is that we could increase the empirical validity of some treatment interventions by demonstrating that they can lower cortisol or decrease amygdala function on this task and so forth.

SJ: What are the most common misperceptions/misunderstandings regarding the impact of traumatic stress on child development?

VC: There used to be this idea that children were resilient just by virtue of being children, but there is no literature to really back that up. In fact, we know the opposite. We know that you are more vulnerable when you are younger, when you do not have defensive styles, when your brain is still developing, when your physiology is still developing. It affects you more.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this interview, which will discuss the treatments and preventative interventions for children with PTSD, the factors that determine how these children will respond to treatment, and the future of the field.

Copyright: Shaili Jain, MD. For more information, please see PLOS Blogs