Optimism

How to Be More Positive

Few people think the world is improving, but data shows we should be optimistic.

Posted May 7, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Is the world getting better or worse?

2017 was considered the worst year ever until 2018 came along. We will probably think the same of 2019.

So, when a survey asked people if they thought the world was getting better or worse, the results were unsurprisingly devastating. Hardly anyone has a positive outlook—only 10 percent in Sweden and 6 percent in the U.S. believe the world is in better shape than it was.

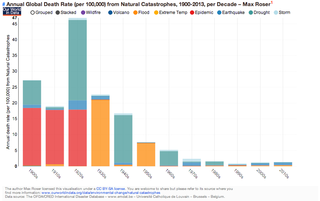

The late Swedish academic Hans Rosling was concerned about this distortion—statical facts offer a different, more positive view. But, the regular news reports on violence, natural catastrophes, terrorist attacks, and wars taint our vision.

As Hans Rosling said, “There’s no room for facts when our minds are occupied by fear.”

Maybe it’s not reality that is broken—what we need is a new lens.

The bright and dark sides of perception

The world’s been coming to an end for a long time.

The Hundred Years’ War was supposed to erase humanity from the face of the Earth, seven centuries ago. People thought the same about World War I. And then came World War II. Something similar happened with pandemics—from the Bubonic Plague to Cholera to AIDS, each outbreak was perceived as the worst ever.

As Franklin Pierce Adams pointed out, “Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.”

We have a distorted lens when it comes to assessing reality. Optimistic and pessimistic people see the world as something static—it’s either perfect or broken.

Extreme pessimism can turn into fatalism—we feel powerless observing how the world is going down. Even worse, thinking that institutions are broken can lead to radicalism—people want to take action in their hands and “drain the swamp.”

Optimism can cloud our self-awareness too—it makes us believe we are better than we actually are. Extreme positivism makes us ignore basic facts or underestimate risks. It leads to poor decision making or inaction.

“A man is but the product of his thoughts. What he thinks, he becomes.”–Mahatma Gandhi

In the book Factfulness, Hans Rosling et al. debunk the fatalist myth: They prove that the world is becoming better and better. As they explain on their website, they are on a mission to challenge our negative views with facts and data.

We are born with a craving not just for fat and sugar, but also for drama. We get bored when nothing terrible happens—dramatic stories feel more appealing. The problem is that our craving for drama distorts our perception. When we let bad stories pile up, we end thinking the world is getting worse.

Multiple statistics show that in the past 2–3 centuries the world has become better and better. Life expectancy continues to rise, child mortality continues to drop, and more people are living in democracies. Progress is not just limited to developed countries but across the board.

The world we live in is not perfect, but it’s not getting worse as most of us think.

Borrow a new lens

Our memory clouds our perspective. By using mental shortcuts—the availability heuristic—we rely on immediate examples that come to our mind when evaluating information or making a decision. The easier it is to recall something from memory, the more probable we judge it to be.

As George Orwell said, “Every generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it.”

Both pessimistic and optimistic people use a binary lens. They appreciate the world in black or white terms—they either see what’s right or what’s broken.

But improving our views requires more than identifying erroneous beliefs—we must borrow a new glass.

As Donald Robertson, the author of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, explains, therapy approaches have moved from coaching people to identify erroneous beliefs to encouraging them to try a new lens.

Robertson shares what he discovered in his own therapy practice. Early on, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) placed a lot of emphasis on identifying one’s incorrect beliefs—people had to question those and replace them with more healthy and rational ways of thinking.

The next generation of therapists realized that changing our beliefs, not only is difficult, but not necessary. What matters is changing our relationship with life events—we must learn to use a new lens.

“The world cannot be understood without numbers. But the world cannot be understood with numbers alone.” ―Hans Rosling

Take our thoughts, for example. We must learn to look at them, not through them. When your thoughts become your lens, your reality becomes foggy, as I wrote here.

"Defusion" is a term coined by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to describe the ability to separate ourselves from our thoughts. Fusion," on the other hand, is when we let our thoughts distort our vision.

The same applies to effective emotion management. Emotional reappraisal—understanding and reframing our emotions—is more effective than suppressing or letting them go wild.

Cognitive distancing is a powerful psychological strategy—it’s about becoming more aware of our thoughts and seeing them from a distance. If you believe the world is either rose-tinted or dark and gloomy, it’s because of the lenses you use. Distancing from events makes you understand the world is not good or bad—your glasses make it look that way.

As Epictetus said, “It’s not things that upset us but rather our opinions about things.”

Marcus Aurelius addressed the need to separate our judgments from external events. We must suspend individual value judgments responsible for unhealthy behaviors. When something makes you feel that your life is getting worse, remember Epictetus's words—it’s not things, but the glasses you use, that upset you.

Wearing a "progress lens" will help you understand the world is dynamic, not static—pay attention to what’s getting better, not just to what’s terrible. It will help you observe the good without being blinded by it either.

A progress lens helps us see the evolution—we focus on improving instead of complaining about what’s broken.

Try the progress lens

“I have found that intellectuals hate progress. And intellectuals who call themselves progressive really hate progress.” — Steven Pinker

We have a hard time accepting the world is getting better. And we are clueless about it.

As Steven Pinker explains on his amazing TED talk, “Some intellectuals have responded with fury to my book Enlightenment Now, saying first how dare he claims that intellectuals hate progress, and second, how dare he claims that there has been progress.”

The need to dramatize our lives creates an opportunity for others to become our saviors. We’ve turned scientists, leaders, gurus, and the media into heroes. When the world seems about to collapse, experts can save us by providing clarity.

But, you don’t need others to see life clearly. Wearing a progress lens will provide you with a sense of autonomy—you can focus on improving things without expecting anyone else to save you.

Acknowledging progress doesn’t mean being naïve. It’s the ability to compare your current status with where you were before. It’s about focusing on the improvement, not on what’s missing.

So, is the world getting better or worse?

Steven Pinker arrived at the same conclusion that Hans Rosling did. If we compare statistical facts, the world has become much, much better when it comes to life expectancy, prosperity, health, peace, safety, and more.

When we watch the news reporting natural catastrophes or war fatalities, we immediately think the world is going down the sink. But, facts show us that the world is getting safer. That doesn’t mean ignoring tragedies like school shootings in the U.S. or the recent hate crime in New Zealand. Acknowledging progress is not idealistic or utopian view.

We have to trust our human ability to improve if we want humanity to continue making progress.

Interestingly enough, most of us are feeling better in spite of our negative outlook about the world. People are feeling happier across the board. In 86 percent of the world’s countries, happiness has increased in recent decades.

Acknowledging progress doesn’t mean ignoring what’s wrong—it energizes us to keep working on getting better and better. Wearing a progress lens will help you integrate all aspects of life by providing a sense of autonomy. You’ll see what’s broken as a problem to be solved, not as something to feel bad about it.

Are you making progress?

Life will never be perfect—you can focus on what’s broken or acknowledge progress instead.

A distorted lens makes us focus on one side the story—we magnify either the negative or the positive. Wearing a progress lens helps us acknowledge our improvement. We know some things are wrong, but ruminating sad events or past mistakes doesn’t help us move forward.

So, which lens do you use to observe your own life?

Appreciating the good is not conformism. It’s about embracing our dynamic and fluid nature—progress makes us focus on the journey, not just on one particular stop. Personal growth requires understanding that we are not changing but becoming.

Try wearing a progress lens. The world is not perfect, but every day it’s getting better and better. When you feel stuck, remember that.

I leave you with one last thought by Steven Pinker:

“We will never have a perfect world, and it would be dangerous to seek one. But there’s no limit to the betterments we can attain if we continue to apply knowledge to enhance human flourishing.”