Anxiety

Is Your Threat Brain Always On?

Why our survival instinct is killing us.

Posted November 30, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

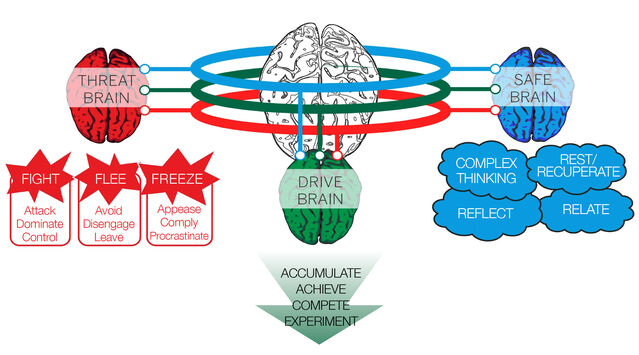

The purpose of our emotions is to motivate action so that we can achieve the basic goals of survival, accumulation, and relationship. Threat brain, our oldest motivation system, enables us to recognise and respond to danger. Drive brain motivates us to seek out pleasurable and rewarding experiences, such as accumulating, achieving, and winning. Safe brain motivates us to rest, recover, and form relationships with others.

We need all three motivational systems working together to balance and regulate each other. Unfortunately, many of us get caught in unhelpful habits that quickly take hold and tighten their grip on us because our motivational systems are "dis-integrated" and out of balance. Usually, the cause of this disintegration is an overactive threat brain. Most, if not all, of our personal and social problems can be traced back to this overactivity.

Threat brain can make us physically ill (the links between stress and ill-health are strongly evidenced), can disrupt our relationships (by triggering and sustaining conflict, avoidance behaviour, and over-compliance), and can lead to distressing personal problems such as addiction, chronic anxiety, shame, loneliness, depression, and suicide.

Our threat brain evolved to respond to, and hopefully survive, life-threatening, physical challenges—in other words being killed, wounded, or starved. In animals, threat brain works as it is intended. It detects and enables the animal to respond quickly to a short-term crisis. Their threat brain is alert but also switches off appropriately. However, as our human brain has evolved and grown, so too has our ability to imagine danger. We conscious creatures are able to create and re-create danger in our minds which triggers the same biological stress reaction as actual danger. Animals do not think about the past and the future, they do not ruminate on "what if?" or, "if only," which means, whilst they may not be as successful as we are in dealing with complex challenges, they are unlikely to suffer the chronic psychological and physical effects of prolonged anxiety and stress.

There are, of course, times when overactivity in our motivational system is useful. For example, if I am about to step in front of a car, I want and need my threat brain to kick in quickly—cortisol and adrenalin will get me moving fast. Or, if I am about to give an important presentation or take part in a sporting competition, I want my drive brain to be highly active, providing a healthy dose of dopamine that stimulates productive energy and enthusiasm. And if I have just given birth, I want my safe brain to be putting in some overtime to provide me with oxytocin to help me bond with my child and recover my vitality.

However, if our motivational systems are dysregulated often or most of the time, we will start to experience difficulties. Workaholism, "compassion fatigue" (caring too much), and anxiety disorders are recognisable examples of what happens when our drive, safe, and threat brain motivations sustain feelings, thoughts, and actions that are inflexible, repetitive, less effective, and sometimes harmful.

Mostly though it is our overactive threat brain that causes us the worst problems. When it is always "on," it shuts off our safe brain capability and makes our healthy drive brain toxic. Toxic drive, which is a threat-motivated achievement, is a common experience in our highly competitive and evaluative societies which reward winning, competing, accumulating, and power. Today it is not at all unusual for people to be living in a permanent state of anxiety and fear—one that is driven by misplaced ambition and sustained by deeply rooted feelings of inadequacy or unworthiness. Too many of us are driven to "keep going" because we fear being exposed as vulnerable or incompetent, and we are usually unaware of these fears and motivations until they disrupt our lives as illness, relationship breakdown, job loss, or mistakes and accidents.

To overcome the problems caused by our overactive threat brain, we first need to notice when we are in threat, and then we need to learn how to regulate this response.

Learn more about how to notice and regulate your threat response in Beyond Threat.

References

Wickremasinghe, N. (2017) Beyond Threat. Axminster:Triarchy Press