Sleep

New Findings on Sleep and Brain Health

New research shows that good sleep may provide protection against dementia.

Posted March 31, 2019 Reviewed by Matt Huston

As research accumulates, we have increasing evidence of the importance of a good night’s sleep. And not just a good night of sleep, but regular, day-to-day, quality sleep. We humans are pretty good at riding out occasional nights or even a few nights of poor sleep and can generally make up for the loss with several nights of good sleep. But routine loss of sleep is a much greater problem. Below are some noteworthy recent findings on the effects of sleep loss.

But first, it’s important that we are aware of the difference between sleep deprivation and insomnia. By insomnia, I mean a difficulty falling and/or staying asleep and having adequate time for sleep. This difficulty results in daytime symptoms like irritability or memory problems. We know that the problem of insomnia is over-arousal — either not being able to relax sufficiently to fall asleep, or becoming aroused upon awakening during the night such that it is difficult to fall back asleep, perhaps for the rest of the night.

Over-arousal can have many causes, but the most common is excessive nocturnal mentation. This nighttime thinking doesn’t have to be anxiety-provoking, just excessive. Reviewing the day’s events over and over again can make it impossible to fall asleep, even if those events were not upsetting or worrisome. Most often, people with insomnia are spending too much time in bed awake and not spending enough time sleeping. They usually are getting enough sleep to function during the day. This is why some of the most effective behavioral techniques for treating insomnia involve reducing time in bed — even though this may initially seem counterproductive. But by decreasing time in bed and having more up time, the drive to sleep is increased, and sleep usually occurs faster and is deeper. This deeper sleep may also eliminate the waking-up experiences that occur during the periods of lighter sleep associated with insomnia. Spending less time in bed to get the same amount of sleep reduces the stress and worry about not sleeping and consolidates sleep so that it is more refreshing.

When people have extremely full and taxing schedules, perhaps due to their jobs and/or to having young children, they may, on a regular basis, be unable to get the full amount of sleep they need. When regularly getting less than 7 or 8 hours of sleep a night, the way is open for dangerous situations, such as drowsy driving and the deadly accidents that can ensue. Sleep deprivation is therefore different from insomnia. People with insomnia usually function well, but may feel fatigued and irritable, while sleep-deprived people are at risk of becoming dangerously drowsy.

I recently discussed the impact of dementia on sleep. Patients with dementia often experience insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, altered circadian rhythms, and excessive movement during the night, such as leg kicks and acting out dreams.

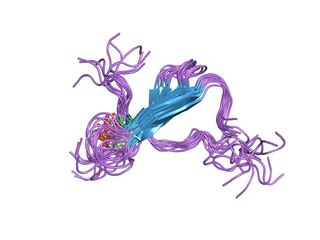

But what about the effects of sleep deprivation on dementia? A recent article by Holth et al (2019) addressed this issue as related to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). They looked at the impact of sleep deprivation on the presence and spreading of b-amyloid (the peptides that form the plaques seen in the brains of AD patients) and tau (a protein produced in brain cells that can become defective and is released into the intercellular space around the neurons). Evidence indicates that Alzheimer’s disease is initiated by the aggregation of b-amyloid, and the accumulation of tau then appears to drive neurodegeneration.

They found that sleep deprivation, in mice, greatly increased the presence and spreading of tau. Tau is manufactured in the cytoplasm of neurons and is released into the intercellular space between them. This is increased during wakefulness when cellular activity is greater, and is increased even further when cells are being challenged due to sleep deprivation. In previous research done by this team, this effect was demonstrated to occur in humans using patients whose cerebrospinal fluid was being monitored by lumbar catheters. One night of sleep deprivation caused a 30 percent increase in b-amyloid and a more than 50 percent increase in tau. In the current study, sleep deprivation was shown to increase the spreading of tau in mice brains.

![Klem [Public domain] Klem [Public domain]](https://cdn.psychologytoday.com/sites/default/files/styles/article-inline-half-caption/public/field_blog_entry_images/2019-03/taijitu_public_domain_2_032915.jpeg?itok=PY3bntND)

The pathological spread of tau through neural circuits in the brain is correlated with the progressive loss of synapses, increased neuronal dysfunction, and greater severity of cognitive and motor symptoms (Nobel & Spires-Jones, 2019). There is most likely a significant bidirectional process in which poor sleep contributes to tau accumulation, which then contributes to neuronal processes that produce poor sleep. Further research using advanced imaging methods will be needed to more deeply explore this relationship.

Nobel and Spires-Jones (2019) also note that while the increase in tau due to sleep deprivation is related to increased cellular activity, the exact mechanism of this remains unknown. For example, it has been found that activities that increase brain activity, such as learning a new language or exercising, seem to actually offer protection against the development of AD. It may be that the damage is related to brain activity occurring in the absence of external stimulation.

It has also been shown that toxic aggregates are cleared during sleep, indicating that sleep provides benefits, while sleep deprivation contributes to negative processes in the brain. Nobel and Spires-Jones suggest that for people at risk of developing dementia, treatments to improve sleep may hold great promise. I wholeheartedly agree with their statement that “the best advice for everyone is to do all we can to maintain a healthy life balance, sleep well, and engage with activities to keep the body and mind healthy” (p. 814).

References

Holth, J.K., Fritschi, SK, Wang, C., Pedersen, N.P., Cirrito, J.R., Mahan, T.E., Finn, M.B., Manis, M.,Geerling, J.C., Fuller, P.M., Lucey, B.P., &. Holtzman, D.M., (2019). The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science, 22 February 2019, 363(6429), p. 880–884.

Nobel, W. & Spires-Jones, T.L., (2019). Sleep well to slow Alzheimer’s progression? Science, 22 February 2019, 363(6429), p. 813–814.