Teamwork

If Aliens Showed Up, Would Humans Stick Together?

How Earthly demagogues take power by citing outside threats offers a clue.

Posted March 15, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- One way or another, the discovery of extraterrestrial life may profoundly affect how we humans view ourselves.

- While humans might view primitive alien life positively, we might be more wary of intelligent extraterrestrials.

This story is true.

It was November 1985, in Versoix, a suburb of Geneva, Switzerland, and the world was still in the icy grip of a Cold War pitting Western democracies against the Soviet Union and its allies. Ronald Reagan, a former B-movie actor, science-fiction fan, and rabid anti-communist turned president of the United States, was sitting down for a chat with Mikhail Gorbachev, the leader of the Soviet Union—the authoritarian communist nation Reagan, two years earlier, had branded "the evil empire."

The two big shots had taken a break from their schedule to walk, and talk informally through interpreters, in a chalet near the official meeting place. They were facing each other in comfortable armchairs beside a hearth bright with a snapping hardwood fire. The talks, both official and unofficial, had not gone anywhere, but at one point Reagan, the sci-fi fan, abruptly asked Gorbachev, "What would you do if the US were suddenly attacked by someone from outer space? Would you help?"

"No doubt about it," Gorbachev replied.

"Me, too," Reagan said.

The Geneva talk did not result in any concrete treaties, but it did provide a breakthrough moment in which each leader recognized the other was serious about trying to stop the nuclear arms race and work toward a form of peace between the two superpowers: a breakthrough that would eventually reach fruition in START, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks of 1991.

And the personal détente between Reagan and Gorbachev, informed by and possibly initiated during that talk about outer-space invaders in the chalet, also casts light on the root dynamics of cooperation and conflict between humans, and the possible effects that the discovery of "someone from outer space," or some form of extra-terrestrial life, might have on how humans choose peace, or war: an issue that can only acquire more relevance as the ex-Soviet Union, in March 2022, under its president Vladimir Putin, continues to pursue a ruthless war against the independent republic of Ukraine.

Cooperation in the Brain

There's little need to search for evidence of how often human tribes, ethnicities, and nations fight, or how they cooperate as well. The fabric of history is woven through with the warp and weft of peace and conflict. In the human brain, the same general areas, the frontoparietal network as well as the anterior insula, light up for either–fighting or making friends, both read the same–although within those areas, University of Washington researchers have found, a wedge of the medial prefrontal cortices is more focused on cooperation (which its authors also claim is "socially rewarded") than on mechanisms of defense.

In the record, there is also ample evidence of how people—usually men—of power have used the threat, and sometimes the reality, of outside invasion to unify divergent factions. Nativist demagogues of various stripes—for example, the Know-Nothings in 1850s America—have often found popular support, usually among the less educated and more vulnerable, by vowing to block the waves of foreign immigrants supposedly invading their native soil.

Too often, the tactic has been used to justify war. As Ian Kershaw wrote in Der Spiegel, Adolf Hitler's "relentless denunciation of the nation's alleged powerful enemies—Bolshevism, Western 'plutocracy,' and most prominently the Jews (linked in propaganda with both)—reinforced Hitler's appeal as the defender of the nation and bulwark against the threats to its survival, whether external or from within."

On the side of the WWII Allies, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor silenced within a couple of hours the powerful "isolationist," anti-war voices of American figures such as radio personality Father Charles Coughlin, Senator Charles La Follette, aviator Charles Lindbergh, and Ambassador Joseph Kennedy. More recently, the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks solidified US public opinion to the point of enthusiastically supporting, and without much tolerance for dissent, America's knee-jerk invasion of Iraq — a country that had nothing to do with the 9/11 attacks, and whose government had been actively inimical to the Islamists responsible.

And, once again, we have the current example of Russia's President Vladimir Putin. For it is widely suspected that the ex-KGB agent plotted his route to power by conspiring with agents of the KGB's offspring, the FSB, to blow up apartment buildings in Russia in 1999, terrorist acts he then vociferously blamed on an external threat—Islamists from Chechnya—despite the fact that the Chechens were no longer at war with, nor had any reason to antagonize, the Russian Federation. The soaring approval ratings for Putin that resulted allowed him to take over as president and initiate another war against the Chechens, thereby consolidating his hold on power.

This is recognizably the same Vladimir Putin who has rallied Russia around the theme of outside threats, from NATO and the West, to prevent neighboring Ukraine from joining forces with the Western enemy. Today's brutal invasion of Ukraine is the result.

Life on Other Planets?

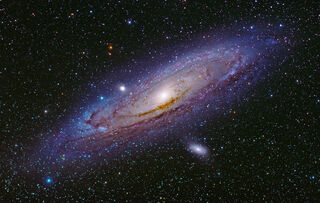

These examples are all, of course, Earthbound. And, while we have no solid evidence of life outside our own planet—despite a large number of unexplained "UFO"-type observations—the sheer size of the known universe, and our knowledge of how RNA-based life on Earth probably came about, makes the existence of other, "alien" life forms statistically very likely.

Just think about those statistics: One-hundred-trillion galaxies exist in the known universe—a number that is essentially impossible for our minds to understand—and each contains 100 billion stars, which adds up to one septillion (1 + 24 zeros) stars. Astronomers reckon each star has at least the same number of orbiting planets. And 7.6 percent of these stars appear to be similar to our own sun, and a quarter of their planets (19 sextillion, or 19 + 21 zeros), according to Keppler observations, are likely be "Goldilocks" ("just-right") planets: Earth-like in terms of size, nature, and proximity to their sun.

Mumbling numbers at the rate of 10 a second, it would take you or me well over a billion years to count up to a sextillion. And there are probably 19 sextillion Earth-like planets that might, in theory, generate conditions not dissimilar to those that spawned life on Earth, without taking into account the likelihood that alien life will be very different from ours (methane-nitrogen ice-spiders, anybody?), and originate in planets that are in important ways not Earth-like.

Which brings us back to that chalet on Lake Geneva, and the immediate question of how humans might react to the detection of alien life of whatever nature. Consciously or not, humans still consider themselves, psychologically speaking, to be unique. Whatever the statistics suggest, we see the universe as a mysterious dark space, silent and empty of life, of which our human consciousness is the bright and noisy hub. Galileo and Copernicus shook up our assumptions when they proved that Earth was not the center of the solar system; Charles Darwin took human arrogance down a notch when he suggested that humans, far from being created by God on the sixth day, were in fact the descendants of apes; but our perception of self is still essentially religious, of a life-form created by a god, or gods, or archetypal animal-spirits, whose uniqueness is in all cases a given.

All that would change if another life form, almost certainly very different from ours (despite the essentially human images of aliens we are accustomed to from "Star Trek" and "Star Wars") were detected on another planet. Suddenly we'd have to perceive Earth not as the cradle of universal consciousness, but as just another planet among many that have given birth to that weird chain-reaction of chemicals we call life.

If, as the odds seem to indicate, some of those life-forms prove in whatever way conscious, it would follow that we might eventually have to interact with them. Earth's history, and the reactions of Reagan and Gorbachev, suggest that the presence of an outside power might allow our own planet's different peoples to recognize and celebrate their essential identity when faced with the prospect of dealing with extraterrestrial beings.

Some evidence suggests that educated humans are OK with nonthreatening, methane-ice-spider-type aliens, and even very religious people might be able to accommodate the idea of life formed outside the precincts of their Earthly god. The SETI (Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) Institute has even promulgated guidelines counseling a rational, open, global, and science-based approach—based on the so-called Rio scale—to dealing with the discovery of extraterrestrial life.

Unfortunately, when it comes to intelligent non-Earthly life, our cultural record suggests that we are more primed to view that as a threat: Witness the countless Klingons and other evil aliens of "Star Trek," "War of the Worlds," "Twilight Zone," and "Independence Day," as well as the pundits who warn that an extraterrestrial civilization capable of getting in touch with us might well be far more advanced militarily than ours. Earth's history reflects that cultural bias, suggesting that our go-to reflex might be to view extraterrestrials as hostile and gird our loins for war.